By Oliver Pearce, Daniel Yeomans and Michael Kelly

North Bristol NHS Trust

Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Published 06 April 2020

On the 16th March 2020, the government announced several measures to help reduce non-essential services in the NHS to help facilitate an increase in inpatient and critical care capacity1. This included postponing non-urgent elective surgery from the 15th April at the latest for a period of at least three months. National orthopaedic guidance has been published, informing departments on suitable strategies handling of trauma patients during the period when there is increased pressure on the NHS from treating coronavirus patients2,3. Below we wish to share our first-hand experience of the reconfiguration of our Major Trauma Centre from the front-line perspective.

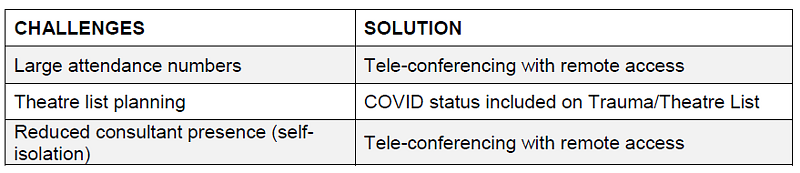

Trauma Meeting

Following the rapid escalation of our national healthcare crisis, our trauma meetings soon became an opportunity to provide staff with updates during the rapidly evolving situation. Following the cancellation of elective services and rapid redistribution of staff to alternative roles, our morning meeting saw a dramatic and concerning rise in attendance, with attendee numbers frequently exceeding forty people. The Major Trauma Centre morning meeting is integral to the efficient coordination of multi-disciplinary teams, utilisation of theatre and outpatient resources. The accurate handover of patient information is vital to ensure timely, appropriate management of often complex trauma patients.

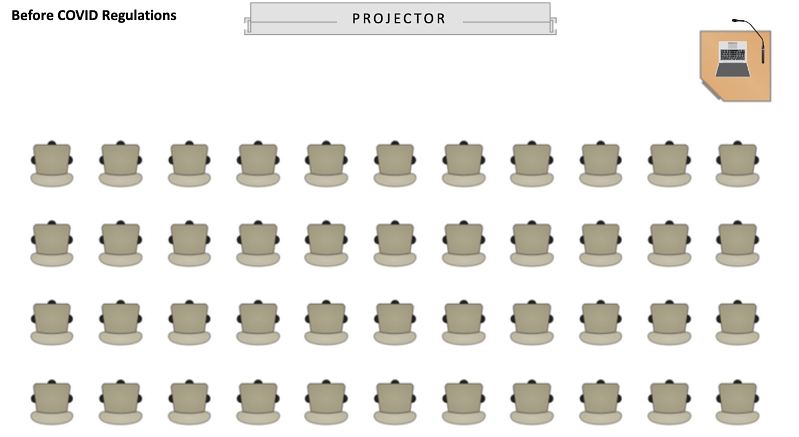

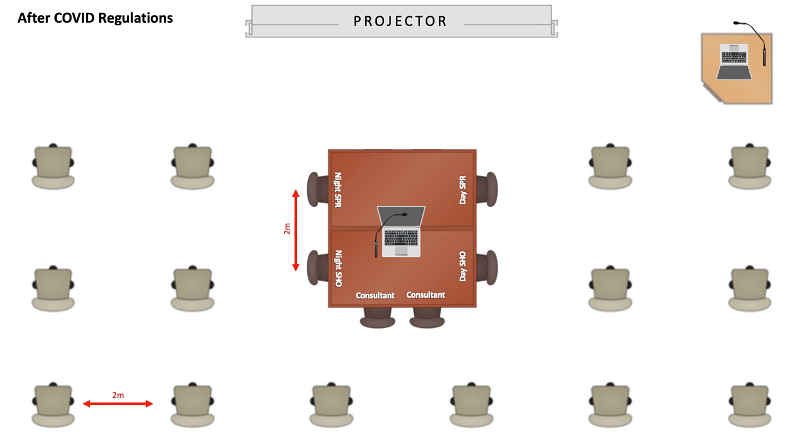

To avoid potential risk of transmission within the orthopaedic workforce we implemented a remote ‘tele-conference’ system with a screenshare broadcast of presented radiographs (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, California). While facilitating access to the trauma meeting for those in self-isolation (5-10 members of staff), this also ensured that we could minimise numbers attending, and only essential staff member were required to be present. Other members of the Orthopaedic department were able to access the meeting elsewhere in the trust, reducing overall attendance by 70%. While maintaining a useful resource for junior members of the team we were able to continue in-depth consultant-led discussions on complex and sub-specialty cases. While using a tele-based system, it is important to design the meeting room appropriately to ensure the successful broadcast of verbal communication and visual cues to facilitate situational awareness to remote participants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 - Diagrammatic room plan of the daily trauma meeting, before and after COVID-19 social distancing guidance. Essential staff members included: Day and night oncall team, one physiotherapist, one orthogeriatric consultant, one theatre coordinator, one anaesthetist, one ward junior doctor, one trauma coordinator representative.

Clarity of communication is essential to facilitate an efficient and safe forum for the multi-disciplinary discussion of patient trauma management. With guidance and infectious disease policies changing on a daily basis it was imperative that suspected or proven COVID-19 status was included as part of patient presentation. We modified our electronic trauma list to ensure COVID-19 status was included with patient information and therefore clearly available for all stakeholders.

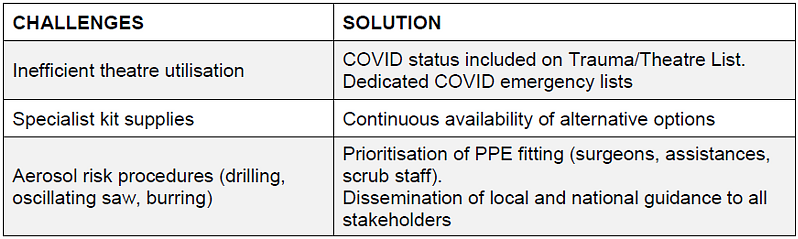

Theatres

List planning has seen a seismic shift in the preparation stages of the corona virus outbreak. Our centre would previously run 2-3 simultaneous trauma lists on a given day, with up to five elective theatres in operation. In line with Government guidance, all elective operating ceased on 16th March 2020. This provided ample theatre space for the re-allocation of the ongoing trauma cases

Theatres previously used for trauma patients, situated adjacent to intensive care, were made available for urgent surgery for any specialty on known or suspected COVID-19 patients. For procedures on such patients, meticulous planning was required to minimise door opening intraoperatively. In line with official guidance, 12 minutes is required before the door can be re-opened4,5. There was no surplus theatre team to staff such theatres, as such any case requiring additional precautions and PPE would be performed by the staff from the initial theatre list assuming the staff member had passed all PPE fitting checks. With the staggered introduction of PPE to staff members, this significantly limited surgeons available to perform such high-risk cases. This challenge was overcome by allocating a ‘PPE ready’ surgeon at the trauma meeting each morning. To facilitate list planning, electronic theatre schedules included additional ‘COVID-19 status’ parameters; negative, pending or positive.

In addition to the two trauma operating lists, the Orthopaedic department ran ‘emergency’ elective lists for cases such as prosthetic joint infections and periprosthetic fractures. Elective administrators worked closely with consultant surgeons to highlight P1 (priority one) patients who required expedited surgery.

Fracture Clinic

The outpatient fracture clinic is routinely one of the busiest clinical environments within an orthopaedic department. Owing to the acute nature of the service, patient turn-over is often fast, efficient and dynamic. Clinicians may adopt a strategy of ‘parallel’ consultations; taking a history, and performing focused clinical examinations on one patient, while the clinician waits for a plaster room or radiology-based intervention to be completed on an additional patient in the adjacent clinic room.

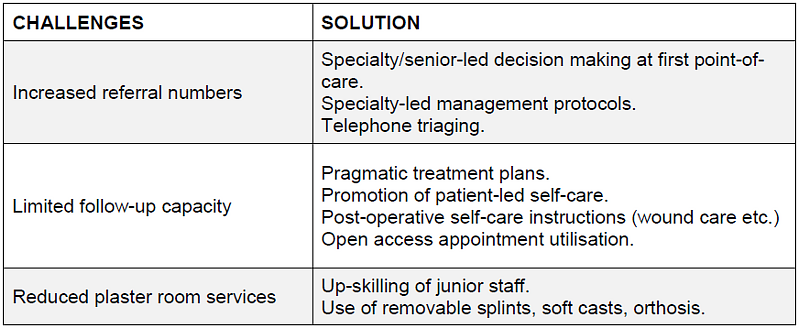

With our clinicians often seeing 15-20 fracture clinic patients on average, this high-volume attendance will provide many challenges in the setting of social-distancing viral transmission risk.

Emergency departments are likely to experience un-precedented demand managing the acutely unwell patient. Although the incidence of minor injuries and trauma is likely to fall as the population self-isolates and naturally avoid high-risk activities, first line treatment of minor injuries will likely be deferred to the fracture clinic pathway. According to published guidance, ‘EDs will change their system and will use triage at the front door and stream patients directly to the fracture clinic before examination or diagnostics’3. In addition to new patient encounters, the follow-up appointments may be redistributed as service provision is consolidated to release practitioners to support a diminished workforce, thereby increasing appointments further.

Going forward, patient-initiated follow-up should be the default position for ongoing treatment plans2. To consolidate fracture clinic appointments further, and avoid unproductive attendances in hospital, we implemented a consultant-directed triaging system to identify patients requiring face-to-face consultations. Given appropriate notice, patients referral documents or previous clinic letters would be reviewed and provided information over-the-phone accordingly, thereby preventing their attendance that same. day. Outcomes of telephone consultation would include appointment deferred, patient self-care with access to future fracture clinic support with ‘an open access appointment’, or discharge from the clinic service following a telephone consultation. All long-term follow-up plans were temporarily postponed until further notice until the critical situation has passed.

Many patients return to clinic for discussion about recent completed investigations and decision about subsequent management accordingly. Early identification of patients with normal results or with self-resolving injuries, may be managed appropriately remotely over the telephone thereby preventing unnecessary follow-up. If suitable, referral for further physiotherapy input can also be achieved remotely, with opportunities for ‘over-the-phone’ physiotherapy education if staff capacity allows.

Total appointment numbers may also be regulated by implementing robust and pragmatic definitive treatment plans. Senior decision-making, and protocol treatment at the first point-of-care care is essential to prevent unnecessary return to hospital with guidelines advocating virtual follow-ups if necessary. Furthermore, the application of removable splints as an alternative to traditional cast immobilisation, may help limit the numbers returning for ongoing plaster care. New departmental protocols have been implemented, including promoting use of fixed ankle boot orthosis and Futura splints for ankle fractures and wrist fractures accordingly, regardless of fracture pattern and radiological parameters. If patients cannot tolerate splints, we have promoted the use of soft-casts to allow patients to remove these themselves in their own home at a specific date. At a national level it is accepted that common upper limb injuries including clavicle fractures, proximal humeral fractures, and wrist fractures will be managed non-operatively, with governing association consensus that complications of malunion being treated with delayed reconstructive options2. Our new local protocols are aligned to such recommendations.

Those patients who require an essential face-to-face appointment, their protection, and the protection of others from potential COVID-19 carriers is essential. We have used simple measures to include the use of segregated adjacent facilities to help distribute waiting patients to comply with ‘social distancing’ guidance6. Fixed seating rows which cannot be physically moved may be modified using cheap solutions including waste disposal bags strategically covering alternative seats to maintain distance between those available for other waiting patients.

Nationally, there will be a shift in management in favour of conservative care of specific injuries where evidence may support surgical or non-surgical approaches. As the NHS capacity reaches a critical level, opting for non-operative care will help reduce admissions, and resource burden in both an inpatient and outpatient capacity. Furthermore, it may protect the patient from potential exposure to a high-risk infectious hospital environment.

Inevitably, management will deviate from the orthodox treatment algorithms normally adopted when the healthcare is not in crisis status. To promote transparency, and the clear communication of rational of care in the immediate and long-term setting, all outpatient correspondence will include a bespoke header to declare that the clinical encounter concerned occurred during a national health crisis. It is unclear at this stage how this statement will provide support for future PALs-related queries or protect clinicians in care-related compensation proceedings.

Minor Injuries & Frontline Treatment

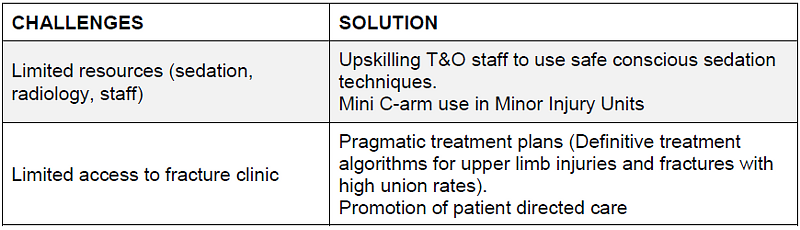

Following the cancellation of all elective services, the workforce was re-deployed to staff a minor injuries unit between 0900 and 1700hrs. The unit itself was situated adjacent to fracture clinic, to utilise the close proximity to radiology and plaster room.

More than half of our clinical workforce in our Trauma and Orthopaedic department work solely in the elective service. With the cancelation of daily clinics and theatre lists we have successfully increased numbers available to help provide senior ward rounds, implement senior-based discharge planning and critically support patient flow. The emphasis of the new service was early streamlined definitive trauma care with the aim of reducing the number of admissions and fracture clinic referrals.

We have designed and implemented a selection of bespoke minor injury protocols to ensure consistent and appropriate definitive management during potentially volatile working environments. They promote early weightbearing status, reduce the burden on plaster room services and encourage patient self-care for conservatively managed injuries. This includes the use of distributing written information on injury management currently used in our minor injuries and fracture clinic services. All patients are provided with an ‘open access’ appointment if they are not progressing at an acceptable rate according to the normal natural history of the injury. A telephone consultation or a face-to-face fracture clinic appointment will then be provided dependent on our service capacity at the time.

Plaster technicians are highly skilled essential members of any trauma unit. We anticipate significant pressures on technician staffing levels during this healthcare crisis. This will lead to significant challenges with the ongoing plaster care of certain patients with a risk of detrimental soft-tissue related complications if not addressed. Pro-active contingency planning has been actioned with the training of junior doctors in application of back-slabs, appropriate sizing of Futura and fixed ankle orthosis and additional casting skills to ensure all levels of the department are self-sufficient in plaster and splint care.

All junior doctors, middle-grade registrars and consultants also received departmental fast-track training for the use of conscious sedation techniques including Penthrox (Methyoxyflurane). Penthrox is currently licensed in the UK and indicated for the emergency relief of moderate-to-severe pain in the conscious adult trauma patient. Key advantages of this patient-controlled analgesia include high-quality pain-relief, and a rapid half-life and post-sedation recovery therefore negating prolonged supervised stay within the minor injury unit7–11.

It is estimated that between 4 and 19.5 per cent of women attending healthcare settings in England and Wales – particularly emergency departments12. It is essential that all staff re-distributed to work in minor injury units have the necessary training to explore and evaluate injuries consistent with domestic violence, abuse and safe-guarding concerns. All T&O staff in our department have been provided with a 24/7 point of contact for highlighting presentations which require further evaluation from the safe-guarding team.

Staff Reallocation & Workforce Planning

During this unprecedented pandemic, departments have a responsibility to ensure that NHS resources, including the availability of clinical staff, are maximised as safely as possible to ensure the best possible care of orthopaedic patients.

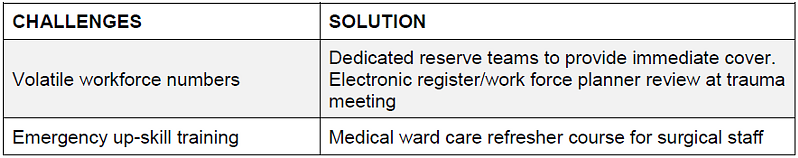

Resilience and ‘flex’ should be incorporated into emergency workforce planning to ensure staff rotas are as robust as possible to allow for multiple daily absences. Staff sickness will remain dynamic with those self-isolating with no means of confirming positive COVID-19 status and heard immunity. Our department was tasked with developing an emergency ‘mega rota’ applicable for foundation trainees through to senior consultants.

Rota design required meticulous preparation. Core service provision and department roles that required continuous staff presence were identified. This included fracture clinic, front-end care at the minor injury unit, trauma theatres, on call duties and ward cover for both major trauma inpatients and an allocated ‘medical step-down ward’ now under our supervision. A specialist middle grade rota was developed to include advanced practitioners and senior associate specialists. In addition, our department identified a lead consultant of the day. It was their role to coordinate resources spread between theatres, minor Injuries and fracture clinic and to ensure all T&O staff were able to attend FFP3 PPE fit-testing services.

Inevitably workforce numbers will be extremely volatile and dynamic, with significant risk of dramatic changes to total numbers available to work. To ensure our rota remained as robust as possible, we incorporated rolling reserve staff, (seven in total) to ensure that there would be seven clinicians available at one time to cover for any last-minute absences. In addition to this, staff were allocated designated rest days to ensure an appropriate recovery period between high-intensity shifts. Each morning, the electronic middle grade rota would be reviewed to ensure a safe level of staffing was possible and to action and last additions from the reserve list accordingly.

Our trust operates a team-based system of junior cover for both trauma and elective patients. With a significantly reduced elective burden. We were able to reallocate Senior House Officers to cover trauma patients. In due course our elective bed capacity was utilised by medical patients. It was the responsibility of the orthopaedic department to see these in patients, supervised by an elective registrar on a rolling rota.

Administration staff and rota coordinators were kept up to date with isolation status of junior staff and planned accordingly. Orthopaedic wards were staffed by allocated juniors prior to the creation of trust-wise mega teams.

In line with national guidance, final year students will have their date of GMC registration expedited in light of the ongoing crisis. In addition to this we are working with our trust to provide employment and training for other clinical medical students as Healthcare Assistants and Porters.

Post-Op & Wound Care

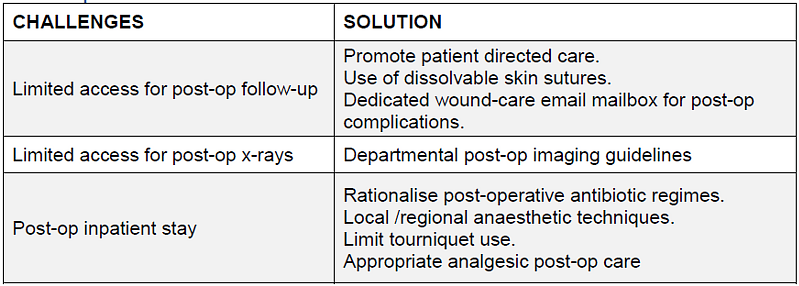

Pragmatic and strategic post-operative care instructions are important to help reduce the burden on inpatient and fracture clinic resources. Our department established a standard operative practice for wound closure, and post-operative instructions for high-volume trauma.

Wound complications are an unfortunate recognised complication of musculoskeletal injuries and orthopaedic surgery. Despite due care and attention at the time of surgery, post-operative wound infections, suture complications and the need for ongoing surgical site surveillance will be required during this challenging time for front-line and follow-up services.

To overcome these challenges, we established a secure departmental mailbox to allow patients to send in photographs of their soft-tissue related concerns to a centralised inbox, accessible to the on-duty fracture clinic team. A pragmatic management may therefore be coordinated without the need of the patient returning to a high-risk hospital environment and minimising unnecessary hospital re-attendances.

Wound closure practice and choice of suture material is often variable in orthopaedic and surgical departments. We enforced use of absorbable suture (Monocryl®, or Vicryl Rapide®) to negate the need for follow-up appointments in fracture clinic or GP practices for removal-of-sutures. Patients were provided with dressings and contact email address where they could send images of their wound if concerned. This inbox was checked daily by the fracture clinic team. For those patients with cognitive impairment, this information would be shared with an available next-of-kin or immediate family member.

To reduce additional exposure risk and transmission of asymptomatic post-operative patients, we plan to limit the use of post-operative check radiographs. Our standard operative practice includes, post-operative imaging of hip hemiarthroplasty only if significant concerns with mobilising at day 2, no routine post-operative imaging of long-bone fixation unless intra-operative concerns avail and requested by the consultant lead surgeon, and intra-operative fluoroscopy should not be followed up with departmental imaging with encouraged use of the mini C-arm to facilitate this. Any need for post-operative imaging should be performed after 3 months in the outpatient setting. As per national guidance, there is no room for imaging to assess for fracture union in the majority of injuries.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has implicated unprecedented rapidly escalating pressures on the National Health Service, with the current generation of the NHS work-force having never experienced such a healthcare crisis to this magnitude. With cohesive team-work, engaged management teams whilst maintaining executive structure throughout, it was possible to seamlessly shift practice of a busy MTC and tertiary orthopaedic centre in a short period of time. In addition, the process has highlighted multiple learning opportunities which will shape future models of practice and escalation procedures.

References

- Stevens MS, Pritchard MA, (2020). NEXT STEPS ON NHS RESPONSE TO COVID-19. NHS England Letter. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/20200317-NHS-COVID-letter-FINAL.pdf.

- British Orthopaedic Association (2020). Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/uploads/assets/ee39d8a8-9457-4533-9774e973c835246d/COVID-19-BOASTs-Combined-v1FINAL.pdf.

- NHS England, (2020). Clinical guide for the management of trauma and orthopaedic patients during the coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/C0274-Specialty-guide-Orthopaedic-trauma-v2-14-April.pdf.

- Public Health England, (2020). When to use a surgical face mask or FFP3 respirator. Available at: https://www.iosh.com/media/7511/when-to-use-a-surgical-face-mask-or-ffp3-respirator.pdf.

- Public Health England, (2020). COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe.

- Public Health England, (2020). COVID-19: Guidance on social distancing for everyone in the UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-on-social-distancing-and-for-vulnerable-people/guidance-on-social-distancing-for-everyone-in-the-uk-and-protecting-older-people-and-vulnerable-adults.

- Porter KM, Siddiqui MK, Sharma I, Dickerson S, Eberhardt A. Management of trauma pain in the emergency setting: low-dose methoxyflurane or nitrous oxide? A systematic review and indirect treatment comparison. J. Pain Res. 2017;11:11-21.

- Coffey F, Mirza K, Lomax M. Abstract 55: The extended efficacy of low-dose methoxyflurane analgesia in patients with severe acute trauma pain: a sub-analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled UK study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(Suppl.1):A21.

- Williams OD, Pluck G. The use of methoxyflurane (Penthrox®) for procedural analgesia in the emergency department and pre-hospital environment. Trauma. 2019;22(2):85–93.

- Coffey F, Wright J, Hartshorn S, Hunt P, Locker T, Mirza K, Dissmann P. STOP!: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of methoxyflurane for the treatment of acute pain. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(8):613-618.

- Grindlay J, Babl FE. Review article: Efficacy and safety of methoxyflurane analgesia in the emergency department and prehospital setting. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:4-11.

- BMA Board of Science, (2014). A report from the BMA Board of Science: Domestic abuse. Available at: https://archive.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/policy-and-research/equality/healthcare-for-vulnerable-group/domestic-abuse-report.