By Rosie Hackneya, Patrick G Robinsona, Andrew Halla,b, Gavin Browna,b, Andrew D Duckwortha,c and Chloe EH Scotta

aEdinburgh Orthopaedics, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, UK

bEdinburgh Medical School, University of Edinburgh

cUsher Institute, University of Edinburgh

Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Asking the question

Trauma and orthopaedic surgery (T&O) is a competitive and popular specialty with applicant competition ratios of 30:1 in Scotland, the highest of any medical or surgical specialty in the United Kingdom (UK)1. Despite this apparent interest in T&O2,3, as a specialty, T&O has been shown to lack the diversity of other medical and surgical specialties, and importantly to lack the diversity of the UK population it serves4,5. Currently, despite over half of all medical students being females4, only 14-19% of T&O trainees are women, the lowest of any medical or surgical specialty5,6. As competition within medical careers grows, demonstrating commitment to a specialty is important with medical students increasingly deciding their specialty early in their medical school career. Students may not necessarily rotate through T&O in the absence of a specific student request. Medical student perceptions of different specialties are thus an important driver for ultimate career selection.

Medical student perceptions of T&O in America have been reported by a number of authors7-9. In response to such studies, programmes such as the Perry Initiative Medical Student Outreach Programme have successfully improved medical students’ perceptions of T&O and increased the success rate of those applying to T&O residency programmes10. However, a UK-based cross-sectional study analysing medical students perceptions of confidence and competence with orthopaedic-related clinical skills, found that almost half of the students reported their teaching as ‘poor’ or ‘less than adequate’11.

We aimed to establish what factors influence student perceptions of T&O and whether direct experience of T&O affects this. Furthermore, we wanted to determine whether students had directly witnessed or experienced discriminatory behaviour in T&O or other specialties, and if so, from what source.

The survey

A web-based survey was created by a team of orthopaedic surgeons and educationalists. This was distributed to students in their fourth year of a six-year medical degree who were engaged in educational activities with T&O between November 2020 and April 2021. These activities included exposure to the online T&O module only, a web-based virtual learning environment that included lectures and live online tutorials with surgical faculty, or a 10-week clinical attachment on the orthopaedic wards in addition to online learning. We also asked students if they had been involved in any self-directed T&O research or clinical activity.

The responders

Of 129 students, 98 (76%) responded to the questionnaire of whom 67 (68%) were female, 14 (14%) identified as LGBTQ+, 52 students (53%) were White British, 29 (30%) were Asian or Asian British, 12 (12%) were other ethnic groups and 5 (5%) were of mixed ethic background.

The responses

As would be expected, liking the subject matter and positive clinical experiences of a specialty were the most important factors for medical students selecting a given specialty as a career. After excluding competition, the most common reasons for not wanting to pursue a career in T&O were students’ perceptions of gender distribution, negative culture, poor work-life balance, and negative stereotypes. A word map demonstrating negative response themes towards T&O is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Wordmap reflecting students’ negative perceptions of T&O.

Gender distribution

Of the students considering a career in T&O (n=31) the ratio of male vs. female students was equal (48% male 52% female). This contrasts a recent study examining career preferences in first year Scottish medical students where men were 2.4 times more likely to want to pursue a career in surgery than women12. However, nearly a third of students in the current study reported the gender distribution in T&O as a reason not to pursue it as a career. Unfortunately this is a well-established reality with a 2018 study reporting that T&O has the lowest female representation of all surgical specialties at 11%13. There is ongoing discussion regarding the cause of the 'leaky tap' in T&O. Though 64% of medical students are female, this becomes 19% in orthopaedic training and 7% at consultant level6. A number of explanations for this centre on role model representation. We found that female and male medical students were equally likely to have male role models (36/67 vs 15/31, p=0.622, Chi Square), but female medical students were more likely to identify female role models (29/67 vs 7/31, p=0.048 Chi square). People entering a career in surgery are twice as likely to do so if they have identified a positive role model14. Same gender mentorship is limited by the low percentages of female faculty and trainees15,16. A recent study of Harvard Medical School students (n=261, response rate 36%) found that 75% had experienced verbal discouragement from pursuing a career in surgery and that women were more likely than men to perceive this as related to gender9.

A recent modelling study from America has demonstrated that if the current rate of growth in female representation in T&O continues, it will take 117-138 years to achieve gender parity18. Diversity is, of course, not limited to gender, but studies on gender highlight that T&O is not becoming diverse by osmosis. Proactivity is needed, and where it is implemented groups such as the Perry Initiative and Nth Dimensions, have demonstrated success in increasing the representation of women and minority groups in T&O training10,17. The diversity within our specialty should reflect the population we serve. Recognising our diversity limitations as a specialty is the first step towards change.

Stereotypes and T&O culture

When considering negative influences on T&O as a career choice we found that negative comments from peers and other clinicians did influence specialty choices and that 30% of students had been influenced by negative comments regarding T&O from physicians. It is unlikely that the impact of such comments is fully appreciated by those who deliver them. As direct exposure to T&O is reduced by many universities secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic and the evolving undergraduate medical curriculum, these comments may have even greater impact. Dissuading an individual student from selecting to rotate through T&O reduces their exposure to it and subsequently has a large influence on their decision to pursue a career in the specialty.

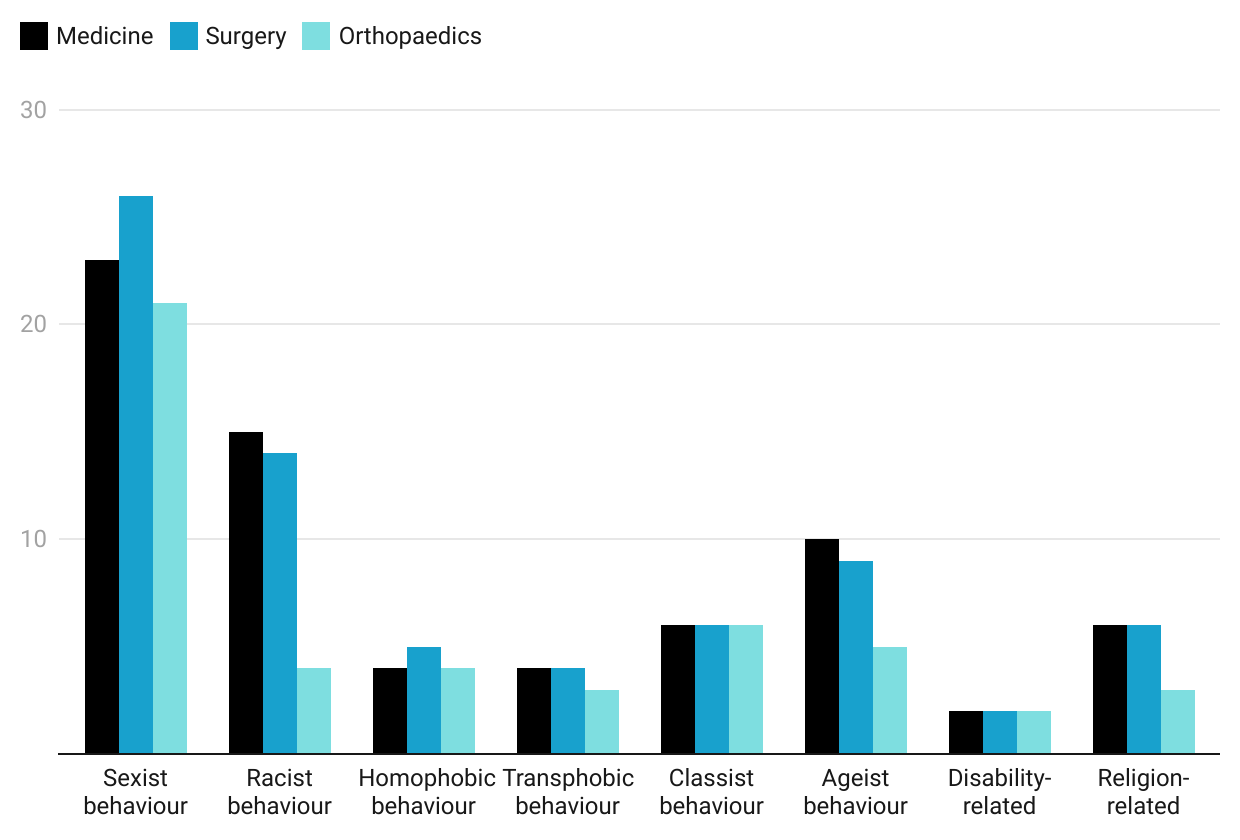

In the current study, 14% of medical student responders identified as LGBTQ+. This proportion is similar to that found by Rahman et al in a similar survey of medical students7. They similarly compared medical student perceptions of T&O before and after rotations finding that women, under-represented minorities and non-heterosexual students generally perceived that orthopaedic surgery is less diverse and inclusive than their more represented counterparts (white heterosexual males), but that on average these views were improved after a clinical orthopaedic rotation. The current study suggests that though other perceptions of orthopaedics may be challenged by direct experience, perceptions of diversity are not: the perception of a lack of diversity in T&O is not a misperception, at present it is a fact. Though levels of witnessed homophobic and transphobic discrimination were low, as with all included forms of discrimination, it was witnessed from multiple specialties and grades and needs to stop. Negative behaviours witnessed by medical students including sexism, classism and racism, were similarly perpetrated by surgeons, students and physicians as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Types of negative behaviours witnessed by medical students per specialty.

Work life balance

Students rated work-life balance as the third most important influence on specialty selection. Again, this is a common theme in T&O surveys16. However, this does not only apply to women. In a study of 234 Israeli medical student’s (male and female) perceptions of six medical and surgical specialties, their perceptions of workload, family time and controllable lifestyle were worst for orthopaedics and general surgery. An international study of medical students also reported that perceptions of heavy workloads dissuaded responders from T&O19. As medical careers generally become more competitive with an increasing invasion of work life balance, perceptions such as these must be challenged through clinical attachments.

T&O exposure

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessarily changed the shape of medical education in the UK with more time spent in the virtual online teaching environment and less time spent clinically. UK medical students have subsequently voiced concerns regarding their preparedness for clinical consultations20. The current study echoes these findings with 34% of students wanting more access to T&O theatre and 46% to T&O clinics. The importance of mandatory musculoskeletal training in encouraging application to T&O residency programs has been demonstrated previously15 with female students 75% more likely to apply to orthopaedic residency training if they have direct exposure as students21. The lack of direct exposure to T&O may worsen diversity issues within the specialty.

Conclusion

This study of medical student perceptions and experiences of T&O in a UK centre found that early in their clinical career female medical students were equally likely to consider a career in T&O as their male counterparts. Gender distribution, stereotypes and perceptions of orthopaedic culture and poor work-life balance deter students from pursuing a career in T&O. Negative comments about T&O from other specialties were common and can influence specialty choices: clinicians should be aware of this. As a specialty, we should assist medical students in accessing clinical T&O environments and emphasise and actively encourage the importance of diversity to our specialty if we are to attract the best candidates and best serve our patients.

Take home message

- Female medical students are equally likely to consider a career in T&O compared to males.

- Students’ cited perceptions of gender distribution, negative culture, poor work-life balance and negative stereotypes as off-putting from a career in T&O.

- Negative comments about the specialty from peers and other medical professionals had been experienced by nearly a third of students.

- Poor behaviours, especially sexism and racism, had been witnessed by a high proportion of students from multiple sources within medicine and surgery.

Author contributions

R Hackney – Data collection, writing of manuscript, final approval

PG Robinson – Study idea, data analysis, writing of manuscript, final approval

A Hall – Data collection, writing of manuscript, final approval

G Brown – Writing of manuscript, final approval

AD Duckworth – Writing of manuscript, final approval

CEH Scott – Study idea, data analysis, writing of manuscript, final approval

Funding statement

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Edinburgh for facilitating the delivery of this study.

Ethical review statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Edinburgh Educational Research Committee (2020/16) for this cross-sectional study of students in year 4 of a 6 year medical degree.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- Health Education England. Speciality Training, Competition Ratios 2020 [Available from: https://specialtytraining.hee.nhs.uk/Portals/1/2020%20Competition%20Ratios.pdf.

- Day CS, Lage DE, Ahn CS. Diversity based on race, ethnicity, and sex between academic orthopaedic surgery and other specialties: a comparative study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92(13):2328-35.

- Daniels EW, French K, Murphy LA, et al. Has diversity increased in orthopaedic residency programs since 1995? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470(8):2319-24.

- General Medical Council. Medical school reports. Available from: www.gmc-uk.org/education/reports-and-reviews/medical-school-reports. [Accessed March 2021].

- Chambers CC, Ihnow SB, Monroe EJ, et al. Women in Orthopaedic Surgery: Population Trends in Trainees and Practicing Surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2018;100(17):e116.

- NHS Digital. Medical and Dental staff by gender specialty and grade AH2667 2019. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/find-data-and-publications/supplementary-information/2019-supplementary-information-files/medical-and-dental-staff-by-gender-specialty-and-grade-ah2667. [Accessed 25/6/21].

- Rahman R, Zhang B, Humbyrd CJ, et al. How Do Medical Students Perceive Diversity in Orthopaedic Surgery, and How Do Their Perceptions Change After an Orthopaedic Clinical Rotation? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2021;479(3):434-44.

- Halim UA, Elbayouk A, Ali AM, et al. The prevalence and impact of gender bias and sexual discrimination in orthopaedics, and mitigating strategies. Bone Joint J 2020:1-11.

- Giantini Larsen AM, Pories S, Parangi S, et al. Barriers to Pursuing a Career in Surgery: An Institutional Survey of Harvard Medical School Students. Ann Surg 2021;273(6):1120-6.

- Lattanza LL, Meszaros-Dearolf L, O'Connor MI, et al. The Perry Initiative's Medical Student Outreach Program Recruits Women Into Orthopaedic Residency. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016;474(9):1962-6.

- Malik-Tabassum K, Lamb JN, Chambers A, et al. Current State of Undergraduate Trauma and Orthopaedics Training in United Kingdom: A Survey-based Study of Undergraduate Teaching Experience and Subjective Clinical Competence in Final-year Medical Students. J Surg Educ 2020;77(4):817-29.

- Cleland J, Johnston PW, French FH, et al. Associations between medical school and career preferences in Year 1 medical students in Scotland. Med Educ 2012;46(5):473-84.

- Moberly T. A fifth of surgeons in England are female. BMJ 2018;363:k4530.

- Ravindra P, Fitzgerald JE. Defining surgical role models and their influence on career choice. World J Surg 2011;35(4):704-9.

- O'Connor MI. Medical School Experiences Shape Women Students' Interest in Orthopaedic Surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016;474(9):1967-72.

- Rohde RS, Wolf JM, Adams JE. Where Are the Women in Orthopaedic Surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016;474(9):1950-6.

- Mason BS, Ross W, Ortega G, et al. Can a Strategic Pipeline Initiative Increase the Number of Women and Underrepresented Minorities in Orthopaedic Surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016;474(9):1979-85.

- Bennett CL, Baker O, Rangel EL, et al. The Gender Gap in Surgical Residencies. JAMA Surg 2020;155(9):893-4.

- Marks IH, Diaz A, Keem M, et al. Barriers to Women Entering Surgical Careers: A Global Study into Medical Student Perceptions. World J Surg 2020;44(1):37-44.

- Bigogno CM, Rallis KS, Morgan C, et al. Trauma and orthopaedics training amid COVID-19: A medical student's perspective. Acta Orthop 2020;91(6):801-2.

- Bernstein J, Dicaprio MR, Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86(10):2335-8.