A practical application of the Intercollegiate Green Theatre Checklist

By Alyss V Robinsona and David Bodanskyb

aCore Surgical Trainee, Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

bSenior Hand Fellow, Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Climate change is one of the defining issues facing healthcare and is the biggest threat to global health1. Forest fires, rising sea levels and extreme weather are directly related to climate change2, and are claiming lives each year. Hence, climate change is a health issue for which clinicians have a responsibility to mitigate. Operating theatres are responsible for 25% of the carbon footprint of a hospital and a significant proportion of plastic waste3. While major systemic efforts are required to overcome this in the long term (i.e., cleaner anaesthetic gases, recapturing systems, renewable building energy), small but meaningful actions by healthcare professionals could have a faster and equally as crucial impact.

However, engaging clinicians in the action against climate change in the workplace, as with anyone else for that matter, is not straightforward4,5. There are few good quality studies establishing behavioural interventions in clinicians to encourage carbon footprint reduction6. There are barriers to engagement; not least the environmental costs of any single action are not experienced by the person directly but spread across the planet (including non-human species and future generations) so any positive changes made may not be directly felt. Clinicians may not have the time or knowledge to think about the environment at work. Climate anxiety and feelings of powerlessness are common5,7, more so amongst younger generations and powerlessness is a significant negative predictor to acting against climate change7. And there are many more specific and psychological theories as to why humans in general could be doing more but do not5.

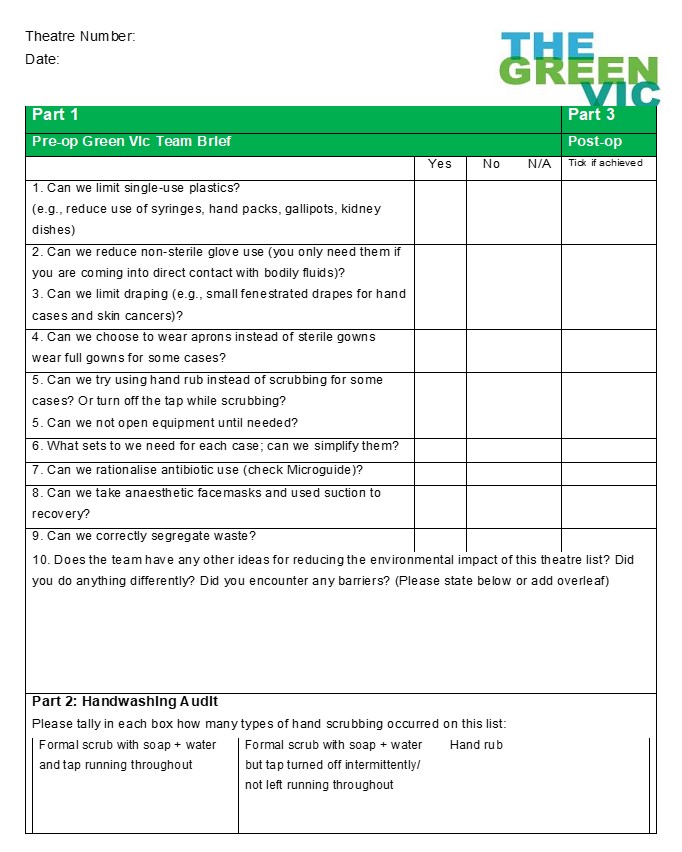

The Royal Colleges of England, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Ireland collectively endorsed the Green Theatre Checklist in 20228. This is an evidence-based compendium which has formulated interventions that can be followed to maintain greener operating theatres. Much as the World Health Organisation Checklist advocates for patient safety, this new checklist advocates for the climate. While the Green Theatre Checklist is an excellent and comprehensive resource, hospitals can engage with it to a varying degree depending on their own resources. For example, it is unrealistic to expect an operating department to reinstall new censored or pedal-operated taps, and surgical textiles are not going to become reusable overnight. There are small changes; using less or smaller drapes, reducing water consumption, turning off lights and computers, which can be done without any major impact on the operation or outcome and such decisions can be made every day. Recognising this, to empower and educate theatre staff to make their own small but impactful changes, we implemented a modified Green Theatre Checklist; selecting achievable goals and asking staff to use the checklist as an adjunct to their daily team brief and debrief during one ‘Green Theatre Week’ (see Figure 1). This was accompanied by appropriate publicity, a ‘Green Suggestion Box’ in the theatre coffee room, and a Green Bulletin.

Figure 1: Modified Green Theatre Checklist

Over the week period, we received 38 returned checklists. 26 of these also completed an integrated hand washing audit. Only six checklists were incomplete. 18 theatres left comments including suggestions and barriers. Of 236 scrubbing episodes, 62 turned off the tap while scrubbing and 52 used hand gel instead of formal hand washing. This is in comparison to a baseline ten theatre lists which were audited including 141 members of staff over 44 cases. In the baseline audit, not one clinician used hand rub for any of the observed procedures. Water usage was calculated at an average of 11.6 litres of water per person.

Therefore, the small impact of the Green Checklist helped to a save 1,183 litres of water, or 116 kgCO2e (based on a carbon footprint of 8.41 kgCO2e per m3 running gas-heated water at 41 degrees9). If continued this could represent a small but powerful impact, which would be increased with further engagement. We also observed a significant number of cases being done with smaller sets, fewer scrubbed members of staff and using non-sterile aprons. More importantly, the ‘Green Theatre Week’ started a conversation: staff became aware of what was for some, a completely novel concept. If integrating environmental sustainability into clinical practice became a social norm, this could break down some barriers to action5. The reception was not universally positive, but it is a work in progress and scepticism surrounding new concepts and processes in medicine is normal. In hand surgery, wide awake local anaesthesia no tourniquet (WALANT) is widely but not universally accepted. Even less so is the concept of ‘field sterility’10. Both concepts have been suggested as means of reducing the environmental impact, with additional benefits of improved efficiency, outcomes and reduced cost11. It takes time to change culture, but the evidence is overwhelmingly in favour of doing so.

There will be more iterations of the Green Theatre Week. People who know more about the causes and consequences of climate change are more likely to take action1, and so improving education for all hospital staff on the effects of climate change and the role of healthcare in environmental sustainability will be crucial in boosting engagement in future. Rewarding clinicians for their collective action, including informing them about carbon savings and innovations elsewhere may help to inspire colleagues to lead action themselves. The conversation, and the action, has started.

References

- Romanello M, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet. 2022;400(10363):1619-54.

- Pidcock R, McSweeny R. Mapped: how climate change affects extreme weather around the world. Carbon Brief 2022. Available from: www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-how-climate-change-affects-extreme-weather-around-the-world.

- Rizan C, Steinbach I, Nicholson R, et al. The carbon footprint of surgical operations. Ann Surg. 2020;272(6):986-95.

- Brick C, Bosshard A, Whitmarsh L. Motivation and climate change: a review. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2021;42:82-88.

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. American Psychologist 2011; 66(4):290-302.

- Batcup C, Breth-Petersen M, Dakin T, et al. Behavioural change interventions encouraging clinicians to reduce carbon emissions in clinical activity: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):384.

- Williams MN, Jaftha BA. Perceptions of powerlessness are negatively associated with acting on climate change: a preregistered replication. Ecopsychology 2020;12(4):257-66.

- Intercollegiate Green Theatre Checklist 2022. The Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburgh and England, and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. Available from: www.rcsed.ac.uk/media/1331733/green-theatre-compendium-of-evidence-rcsed-161022.pdf.

- Environment Agency 2009. Quantifying the energy and carbon effects of water saving; full technical report. Available from: www.waterwise.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Energy-Saving-Trust-2009_Quantifying-the-Energy-and-Carbon-Effects-of-Water-Saving_Full-Technical-Report.pdf.

- Yu J, Ji TA, Craig M, et al. Evidence-based sterility: the evolving role of field sterility in skin and minor hand surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(11):e2481.

- Van Demark RE, Smith VJS, Fiegen A. Lean and Green Hand Surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43(2):179-81.