Did the opening of the Cambridge Movement Surgical Hub (CMSH) improve trainee opportunities?

By Harshvir Singh Grewal

5th year medical student, University of Cambridge

|

This is a runner-up essay from the 2025 BOA Medical Student Prize Entrants were asked to write a Quality Improvement Project (QIP) and how it has equipped them and their department to perform better. |

Introduction

The Cambridge Movement Surgical Hub (CMSH) opened in November 2023. It aimed to increase orthopaedic capacity by 20%, targeting 2,700 procedures annually1. However, to achieve Get It Right First Time (GIRFT) accreditation, CMSH must also demonstrate improvements in “Staff and Training”2.

Since COVID-19, orthopaedic trainees have faced declining logbook numbers, exacerbated by increasing waiting list pressures3. Elective hubs like CMSH are seen as potential solutions, but their success requires measurable outcomes.

This Quality Improvement (QI) project evaluates whether CMSH achieved two primary objectives:

- Increasing the number of elective orthopaedic procedures at Cambridge University Hospitals (CUH)

- Enhancing training opportunities for orthopaedic trainees at CUH

Objectives and methodology

To assess the impact of CMSH, the following metrics were analysed:

- Number of Elective Operations

- Trainee Involvement: proportion and total number of surgeries performed by non-consultant grade surgeons as primary surgeon

- Operating Times

Data analysis also focussed on major joint arthroplasty, key for trainee skill development, and nationally numbered trainees.

Data was collected from the EPIC system, comparing the pre-hub period (January-March 2023) to the post-hub period (January-March 2024). A total of 780 elective operations were analysed using a standardised proforma.

Results

1. Number of Elective Operations

The total number of elective surgeries increased from 259 in 2023 to 519 in 2024, a 100.4% rise. Specifically, the number of major joint arthroplasty cases doubled, rising from 108 to 219, a 102.8% rise.

2. Training Opportunities

Our initial analysis looked at all non-consultant grade surgeons.

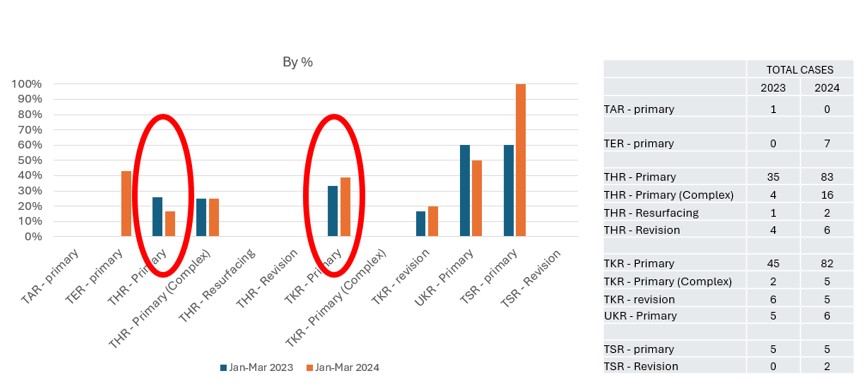

Figure 1: Proportion of surgeries performed by non-consultant grade surgeons as primary operating surgeon.

The proportion of surgeries primarily performed by non-consultant grade surgeons remained unchanged (Figure 1). This trend was most evident when analysing the highest-volume operations: total hip replacements (THR) and total knee replacements (TKR). The only exception was total shoulder replacements (TSR), increasing from 60% pre-hub to 100% post-hub.

Figure 2: Raw number of surgeries performed by non-consultant grade surgeons as primary operating surgeon.

However, as the total number of operations performed doubled, the total number of operations where non-consultant grade surgeons are primary surgeon doubled (Figure 2). Notably, significant increases in training opportunities were observed for knee (100%) and hip (50%) surgeons.

Nationally numbered trainees were also specifically analysed.

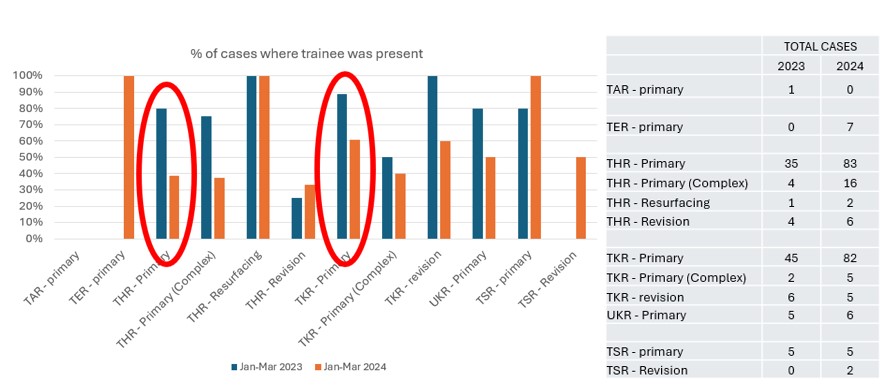

Figure 3: Proportion of surgeries where a nationally numbered trainee was present.

Focusing on the highest-volume surgeries (THR/TKR), there was a decrease in trainee presence following the opening of the hub (Figure 3). However, an exception to this trend was observed in upper limb surgeries (TER/TSR), where trainee involvement increased.

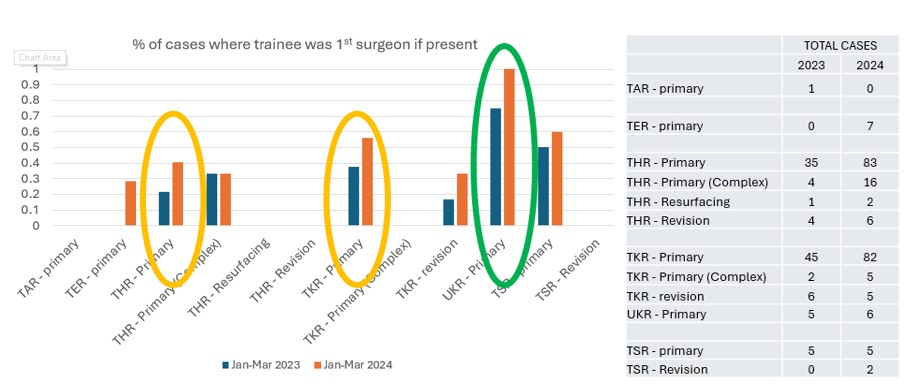

Figure 4: Proportion of surgeries where, if a nationally-numbered trainee was present they were the primary operating surgeon.

When trainees were present, they were more frequently assigned as the primary surgeons, with a particularly high rate observed in unicompartmental knee replacements, where trainees served as primary surgeons in 100% of cases (Figure 4).

3. Operating time

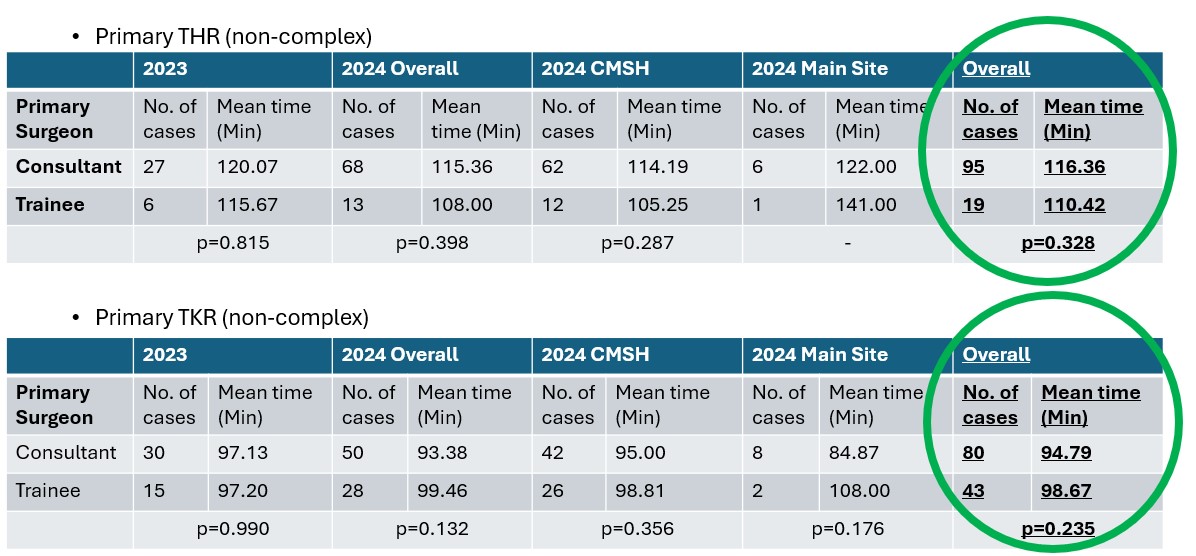

Figure 5: Mean operating time for THR/TKRs pre- and post-hub opening, with a comparison between the Main Site CUH and CMSH.

When looking at THR/TKR, trainees performed these operations within comparable times to consultants, dispelling concerns about longer surgical times (Figure 5). However, it is important to note that in most cases where the trainees were the primary surgeon, they were supervised by a consultant who was scrubbed in.

Discussion

While the CMSH has doubled elective surgeries and training opportunities, more can be done to optimise trainee involvement. To improve this, several potential solutions can be implemented. First, using dedicated training lists with allocated trainers and trainees would ensure that training opportunities are systematically assigned, rather than left to the discretion of the surgeon. Second, establishing parallel operating lists for senior trainees, where one consultant can supervise two senior trainees, would effectively double the available training opportunities. Third, using dedicated hub-based trainee placements could further increase the volume of simpler elective surgeries performed by trainees, thereby enhancing their experience and involvement.

These strategies have the potential to further enhance trainee engagement and training outcomes, maximising the benefits of the elective hub while ensuring the continued delivery of high-quality care.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, several operating lists were lost due to strike action. However, similar losses occurred both pre- and post-hub, with four days lost to nursing strikes in 2023 and seven days lost to junior doctor strikes in 2024. Additionally, while some lists at the The Princess of Wales Hospital, Ely in 2024 were cancelled to ensure that the hub lists were filled, the Ely day surgery unit was not included in this analysis. Furthermore, as the hub was still new, there may have been some reluctance among consultants to use the initial lists as training opportunities. Another limitation is that there were two separate cohorts pre- and post-hub, which may have resulted in different trainee allocations to different consultants, making comparisons between the two groups less reliable. Finally, there were issues with surgeon data recording on EPIC. Surgeon details recorded by theatre staff on EPIC did not always match the operation notes written by the surgeons, leading to inconsistencies in the data.

Conclusion

The opening of the elective hub has resulted in several positive outcomes. It has doubled the number of elective orthopaedic surgeries performed at CUH and doubled the number of training opportunities offered by CUH. Additionally, it has allowed trainees to act as the primary surgeon more frequently when they are present, though they are present less often. Importantly, it has been shown that trainees take no longer than consultants to perform THR/TKR. However, the opening of the elective hub has not increased the proportion of operations performed by non-consultant grade surgeons.

Despite these challenges, the data highlights the potential for CMSH to become a model for integrating training into high-volume elective care.

Bibliography

1. Cambridge Movement Surgical Hub, Cambridge University Hospitals. www.cuh.nhs.uk/about-us/addenbrookes3/cambridge-movement-surgical-hub.

2. Proudfoot, M., 2023. Surgical hubs - Getting It Right First Time - GIRFT. https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/hvlc/surgical-hubs/.

3. Dattani R, Morgan C, Li L, Bennett-Brown K, Wharton RMH. The impact of COVID-19 on the future of orthopaedic training in the UK. Acta Orthop. 2020;91(6):627-32