Odontoid fractures in the elderly – Evidence, ethics, and evolving strategies

By Elie Najjar

Spinal Surgeon, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals

As a spinal surgeon working within a major trauma centre, I have seen the odontoid fracture evolve from a radiological curiosity into a frontline ethical dilemma.

I remember the first odontoid fracture I encountered as a registrar. Mrs D, 84, a keen gardener, had tripped on her garden steps. Her CT showed a Type II fracture of the odontoid process. No neurology. Her family wanted surgery — “We don’t want to take any risks,” they said. But the risk wasn’t just in the fracture. It was in everything around it: frailty, comorbidities, expectations.

Years later, odontoid fractures in older adults still demand more than surgical skill — they demand reflection.

Cervical fractures in the elderly: A tipping point

Cervical fractures make up a substantial proportion of spinal trauma in older adults. Odontoid fractures—especially Type II—are the most common subtype, accounting for up to 85% of C2 injuries in patients over 65 years old1,2.

Low-energy falls are the typical mechanism. Yet the consequences can be profound: one-year mortality rates range from 28% to 50%3,4. These injuries often lead not just to morbidity but to institutionalisation, dependency, and death5.

And yet, many patients present without neurological deficits. The challenge is not the fracture — it’s the context.

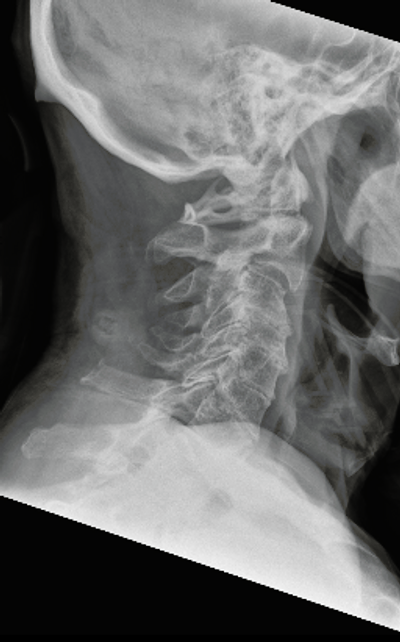

Figure 1: Lateral X-ray of an 80-year old woman with odontoid type 2 fracture, after a fall from height.

Scan the neck, not just the CT

CT scanning has become standard, particularly in low-mechanism falls. The modified NEXUS criteria offers a safe framework in low-risk elderly patients, especially when applying baseline mental status and visible signs of trauma as more reliable predictors than classical distractors6.

But even when the diagnosis is clear, management is not.

Conservative management: The collar debate

Traditional teaching advocated hard cervical collars for Type II fractures. Halos were the gold standard. But the evidence has shifted.

Waqar et al.’s systematic review of 714 patients found no difference in union rates between halo and hard collar for Type II fractures — yet significantly higher complication rates with halos, including aspiration, pneumonia, and delirium2. Coleman et al. showed similarly high non-union rates in both soft and hard collar groups, but with no significant difference in outcomes once age was adjusted6.

In practice, many elderly patients tolerate collars poorly. Dysphagia, discomfort, skin breakdown, and cognitive decline are frequent companions. For some, no collar may be safer than a rigid one.

Sometimes the best treatment is not a screw or a collar, but a conversation.

Surgery: A tool, not a reflex

Posterior C1–C2 fusion and anterior screw fixation both offer stability and higher union rates. But with surgical intervention comes risk — especially in frail older patients.

The INNOVATE study, a prospective multicentre trial, found no significant difference in clinical outcomes or Neck Disability Index improvement between surgical and conservative groups at one year5. Moreover, pseudoarthrosis — so long feared — did not correlate with worse outcomes.

In our practice, surgical fixation is usually reserved for patients under 80 with good bone stock, minimal comorbidities, and a high pre-fracture functional baseline.

Pseudoarthrosis: Failure or function?

It’s time we stopped equating radiographic non-union with clinical failure. In both the INNOVATE study and others, patients with fibrous non-union remained mobile, independent, and pain-free5.

What we once viewed as failed healing may, in fact, be a form of adaptive stability.

“I don’t want to be fixed,” one patient told me. “I want to be home.”

Figure 2: CT scan of odontoid fracture non-union with sclerotic edges and fibrous tissue.

Predicting risk: The role of Hounsfield Units

Emerging evidence suggests that Hounsfield Units (HU), measured from CT scans, offer a non-invasive proxy for bone density. Iyer et al. propose that lower HU at C2 correlates with higher risk of non-union and may guide decision-making in anterior screw fixation7. Patients with HU <150 may fare better with posterior fusion — or no surgery at all.

It’s not about protocols — it’s about the person.

Reframing the question

Instead of asking “How do we fix this fracture?” we should ask:

“How do we preserve this person’s dignity, function, and autonomy?”

The answer might still be surgery. Or a collar. Or simply reassurance. But it should always be the patient’s answer, not just the radiologist’s.

References

- Iyer S, Hurlbert RJ, Albert TJ. Management of Odontoid Fractures in the Elderly: A Review of the Literature and an Evidence-Based Treatment Algorithm. Neurosurgery. 2018;82(4):419-30.

- Waqar M, Van-Popta D, Barone DG, Sarsam Z. External Immobilization of Odontoid Fractures: A Systematic Review to Compare the Halo and Hard Collar. World Neurosurg. 2017;97:513-7.

- Daneshvar P, Roffey DM, Brikeet YA, Tsai EC, Bailey CS, Wai EK. Spinal cord injuries related to cervical spine fractures in elderly patients: factors affecting mortality. Spine J. 2013;13(8):862-6.

- Tran J, Jeanmonod D, Agresti D, Hamden K, Jeanmonod RK. Prospective Validation of Modified NEXUS Cervical Spine Injury Criteria in Low-risk Elderly Fall Patients. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(3):252-7.

- Huybregts JGJ, Polak SB, Jacobs WC, Arts MP, Meyer B, Wostrack M, et al. Surgical versus conservative treatment for odontoid fractures in older people: an international prospective comparative study. Age Ageing. 2024;53(8):afae189.

- Coleman N, Chan HH, Gibbons V, Baker JF. Comparison of Hard and Soft Cervical Collars for the Management of Odontoid Peg Fractures in the Elderly. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2022;13:21514593211070263.

- Egu C, Najjar E, Komaitis S, Essiet E, Akintunde S, Sibanda V, et al. Evaluating the prognostic role of computed tomography Hounsfield units in anticipating spinal outcomes post-instrumentation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2025;34(4):1420-32.