What really matters?

By Hiro Tanaka

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, South Wales

A blink of an eye

Did you know that the human blink of an eye lasts a third of a second. You and I are right now blinking 20 times a minute which means that our eyes are closed for 10% of the time that we’re awake. Despite that, it’s imperceptible to us, it’s as if our mind edits out the time as if it never happened. And yet a lot can happen in a third of a second.

When we look up to the night sky, in the vastness of our universe, 300 stars will explode in a spectacular supernova every blink of an eye. On our planet, over 3,000 bottles of coke will be drunk every blink of an eye. In fact there are so many plastic bottles of coke on this earth right now that if they were laid end to end it would reach the moon and back… 1,000 times. Within our NHS, 1.5 million patients are treated every 36 hours meaning that on average 17 patients receive treatment every blink of an eye.

So much happens around us that we never see or think about. What do you think we’d see if stopped blinking and really looked at ourselves and the people around us at work?

I’m going to invite to you to take a step back from our clinical minds and ask ourselves the question: “What really matters?” in our work. What are the things that really allow us to find true happiness in the work that we do, sustain it throughout our lifetime and be successful in delivering the highest quality of care to our patients?

The problem is that we’re all trapped inside our own minds. We create our own life stories where we’re the heroes and we pick and choose who and what to include in our story. Like a good movie, we edit and delete the things that happen to us and these are influenced by our beliefs which we often inherit from our parents. For example, we go out into the world thinking that in order to be successful we have to be strong and not show any weakness. Or that we have to please people in order to be loved or that we have to be perfect in everything we do. Or that whatever I do, I’ll never be good enough.

Each one of us is searching for the same thing. Now I can’t help you in the love department and I’m the last person to be telling you how to live a healthier life. But maybe we can explore what it means to be truly happy in our work.

In order to do that we have to let go of two things. Firstly, we need to realise that the stories we tell ourselves about our own lives are just fiction and only exist in our own heads. No one else sees it and they probably don’t care that much anyway because they too are struggling with their own stories. Secondly, true happiness comes from lasting satisfaction. We often confuse pleasure that we get from passing an exam, buying that new car, getting recognition from our peers or getting elected to a position of authority as happiness but we all know that it doesn’t last. It becomes an addiction where we end up striving for the next hit of success, something that Arthur C Brooks calls the 'hedonic treadmill'.

So I’m going to share with you three personal stories from my life where I learnt the meaning of lasting happiness in my life and work. The irony is that it’s often through pain that we find true meaning.

The hedonic treadmill

Early on in my career, I was definitely on that hedonic treadmill. Three years into my consultant appointment, I was Clinical Director with a full private practice and working every other Saturday. At the time, I was earning three times more than I do today but at no point in my life did I feel poorer. For four years, I missed virtually every bath time with my daughters who were four and two at that time. One day, after I’d been away for a week, I came home late at night and I remember the strangest feeling walking into my own house as if I was sneaking into someone else’s home. As I walked up the stairs, I felt faint and I managed to get to the bedroom where I collapsed with SVT. As I lay on the floor, I remember my wife crying saying, “Why are you doing this to us? Why are you doing this to us!”. And all I could say was “I’m doing it for us”. To this day, I’ll never forget what she then said. She said, “No… you’re doing it for yourself”. It was her that made me realise just how much I was hurting myself, my family, colleagues and my patients in the pursuit of my goals.

I believed that I should build my career like building blocks. Provide a good living for my family. Be seen to be the best at what I do. Get the respect of my peers and get recognition for the work that I do. And leave a lasting legacy of my career so I’ll be remembered. How wrong I was.

The flaw in this belief is best described by the parable of the three stonemasons. It dates back to the Great Fire of London. As St Paul’s Cathedral was being rebuilt, Sir Christopher Wren visited the site and one morning he spoke with three stonemasons working on the foundations. He asked the first stonemason what he was doing. “I’m making blocks of stones to feed my family”, he said in a rather uninterested voice. He asked the same question to the second stonemason who said, “I’m making a perfect block of stone so that it’ll fit into the wall over there”. The third stonemason seemed happiest in his work and was clearly the leader of the group and when asked the same question he replied, “I’m building a cathedral”.

We could spend our entire careers making blocks of stones, not understanding the greater difference our work was doing or shall we say at the end of our careers that we built a cathedral?

Search for purpose

Dan Beuttner is an Emmy award winning journalist. In 2005 he published the cover story in the National Geographic entitled 'The secrets of a long life'. He had spent 20 years travelling and researching places in the world which he called 'The Blue Zones'. One such place is the village of Ogimi on Okinawa island in Japan. It’s a normal village made up of families and children except for one odd fact. At the last count, of the 3,000 villagers, 1 in 200 were centenarians and 6 out of 100 are in their 90s. Comparing that to pre-COVID times in the UK, only 2 in 10,000 were above 100 and 9 out of 1,000 are in their 90s. The difference is staggering, some 20 fold difference in longevity! Beuttner’s research sought to explain why. It comes down to three factors: diet, genetics and Ikigai which is widely practiced by the islanders.

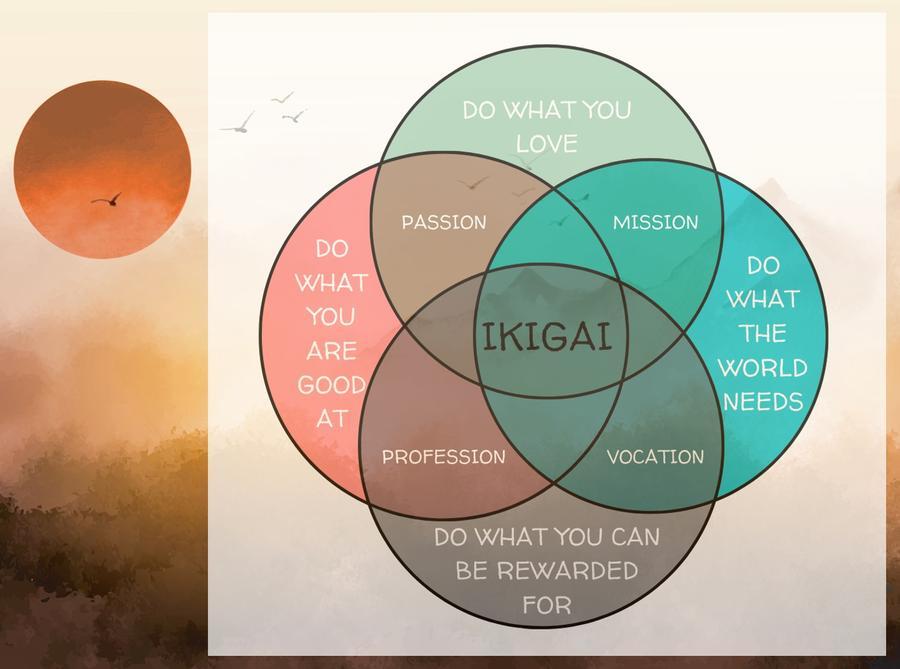

So what exactly is Ikigai? It’s an age-old Japanese ideology which means “a reason for being”. Ikigai lies at the centre of who we are as individuals. During our career, in order to be happy, we must find balance. When we’re on the hedonic treadmill we focus upon the things we get paid for and the things we’re good at. Fortunately, we’re lucky in that the world needs our talents but we can easily forget to do the things we love doing and it’s that which gives us purpose.

Arthur Brooks calls this the Pivot and it’s particularly important for those of us in the latter half of our careers. During the first half of our career we have what he calls fluid intelligence which allows us to perform at our work pursuing those worldly rewards. But as we age into our 40s and 50s we start losing that ability and we develop a different form of intelligence, crystalline intelligence in the form of wisdom and experience. This is what allows us to pursue goals greater than ourselves and help others by mentorship, coaching and teaching. Those of us that don’t recognise that can become afflicted by the Striver’s Curse. We can end up in an addictive cycle searching for that next hit of success. We put ourselves at risk of taking up jobs we hate just for its title, pursuing dangerous sports to prove that we can still do it, purchasing that sports car we don’t need and performing untested surgical procedures to expand our surgical expertise. These are just to name a few…

Friends or family?

They say that you can’t choose your family but you can choose your friends. When I was looking for my consultant post back in 2005, there wasn’t a job for me in Wales and I applied for a job at the Hillingdon as the only F&A surgeon for the unit. I was the only one shortlisted and I spent a week getting to know my future colleagues and the staff. I remember that the night before the interview, I was waiting for the bus outside the hospital in the cold and my friend Hari rang me. He had mentored me in my career and had taught me most of what I knew.

During that call he told me that he wanted what was best for me and that the Hillingdon was a great place with amazing private practice and great opportunities. But he wouldn’t forgive himself if he didn’t tell me what an amazing life and great things we could achieve together and that he’d secured a job for me if I agreed to come back. I didn’t know at that time that he’d actually threatened to resign if management didn’t fund my post! After discussing it with my wife, we realised that it’s the people that we work with that make the biggest difference and even when I spoke with my future colleagues on the very day of the interview, they said that if I had a colleague that was willing to do that for me, then that’s the place I should work. My career wouldn’t have been the same without friends like Hari. Surround yourself with colleagues who make you a better human being and surgeon.

I was blind

My final story is about Steve. Steve trained in regional anaesthesia in Cambridge and was appointed at the same time as me in 2005. I remember the discussions we had back then about whether it was even possible to perform day case awake foot and ankle surgery. Bear in mind that F&A surgery at that time was almost all overnight under GA. Over the course of the next nine years we experimented and developed much of the models of care and pathways which exist today.

We used to do our private list together on a Tuesday after which we would go for dinner or drinks and chat. One of our favourite places was a Sri Lankan restaurant in Cardiff and I still remember the day where he told me that he’d been receiving treatment for Seasonal Affective Disorder and that he was leaving the UK to work in New Zealand. I would have been sad to see him leave, he was my friend and we’d built so much together but he had three little girls and a wife he needed to think about. So we agreed we’d have dinner again a couple of weeks later.

I got a phone call late that Sunday. They found Steve in the anaesthetic department. He’d taken his own life and left his three girls without a father. What a waste of a beautiful life. Maybe I didn’t understand just how serious his depression was or I didn’t ask hard enough. To this day I don’t understand but I can’t help thinking about how blind I must have been to his pain.

Now, every time I go to the F&A unit, there are echoes of Steve everywhere in what we do. From the block room, to what we say to our patients, to the pathways and the stories we tell each other. And even now, our F&A surgeons go out on Tuesdays for dinner because that’s when Steve and I used to go.

We leave a part of ourselves in the stories of the people that we work with. The achievements and accolades that we gain in life will disappear and be forgotten but the memories of what we do for each other will last. There’s so much more that happens in the lives of the people around us that we never see. Especially now, shouldn’t we stop blinking, open our eyes and support the lives of our colleagues that we work with?

When I think about the state of the NHS today it fills me with sadness but I have hope. Hope that maybe out of this madness comes a new paradigm. A new way of working where we can finally focus on the things that matter the most. A blink of an eye only lasts a third of a second, in that time our world can change and it’s up to us to decide how.