An audit of the delivery of paediatric orthopaedic services at the Bristol Royal Children’s Hospital in response to the British Orthopaedic Association Standards for Trauma (BOASt) COVID-19 guidance

By James Berwin, Matthew Singh, Charlotte Carpenter, Thomas Knapper, Sebastien Crosswell, John Kendall, Simon Thomas and Fergal Monsell

Department of Paediatric Orthopaedics, The Bristol Royal Children’s Hospital, Bristol, UK.

Corresponding author email: [email protected]

Published 10 May 2020

Background

The British Orthopaedic Association Standard for Trauma (BOASt) titled ‘Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic’1 provides guidance for the management of adults and children requiring urgent and non-urgent inpatient and outpatient orthopaedic care.

There has been growing concern about the role played by asymptomatic children in the spread of infection2. The ‘BOASt COVID-19’ standards emphasise the importance of balancing optimum treatment of a patient’s injury or condition against clinical safety and resources.

We assessed our compliance with the ‘BOASt COVID-19 standards’ pertaining to children to determine whether it is possible to run a safe and effective paediatric orthopaedic service during these challenging times.

Methods

We performed a prospective audit of the paediatric orthopaedic service at the Bristol Royal Children’s Hospital (BRCH) in all clinical areas from the 16th March to the 16th April 2020.

Our service was audited against the BOASt standard for the, ‘Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic’; last updated on the 21st April 20201.

We also performed a retrospective audit of elective and trauma operating from the same month last year (16th March – 16th April 2019), to assess the impact on workload and case mix following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Fracture clinic

From the 16th March – 16th April 2020, 228 patients were booked into our acute fracture clinic, 291 patients were booked for fracture clinic follow-up.

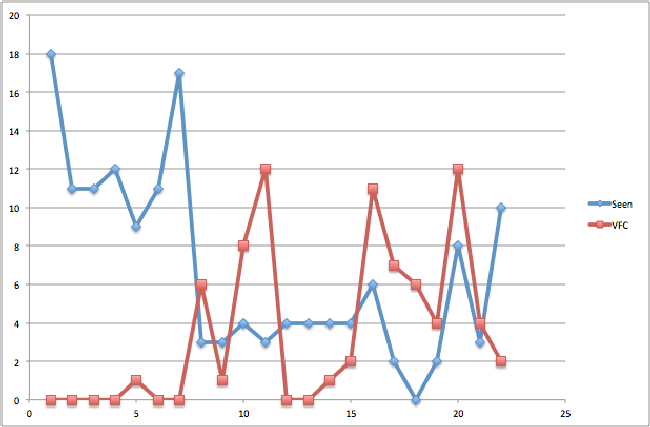

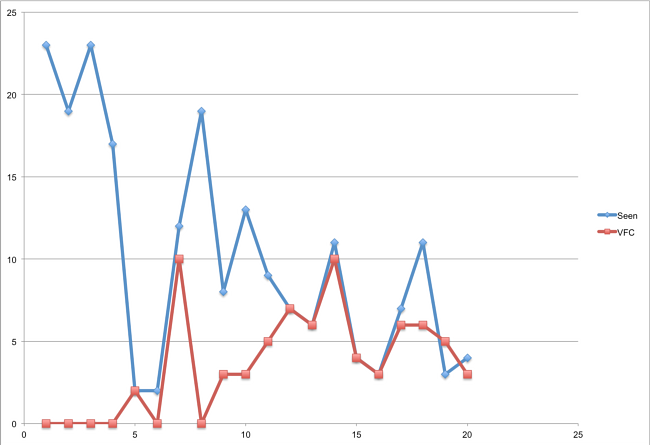

Prior to the COVID-19 era, our department did not run a virtual paediatric fracture clinic. The number of new or review fracture clinic (72%) and new or review virtual fracture clinic (VFC) patients (22%) were identical and the observed trend was a reduction of face to face and an increase in VFC consultations (Figure 1a and 1b).

Figure 1a: A graph showing the number of acute fracture patients seen vs the number of acute virtual fracture clinic patients over the course of the month.

Figure 1b: A graph showing the number of review patients seen vs number of review virtual fracture clinic patients over the course of the month.

Additional resources

The total number of radiographs performed was low and radiographs were not utilised in 81% of patients attending the acute fracture clinic and 64% attending for follow-up.

Removable Softcast was used in 61% of acute fracture clinic patients and 13% of follow-up fracture clinic patients. Plaster room intervention was not required in 69% of patients attending the acute fracture clinic and 60% in the follow-up clinic.

Clinic outcome

In the acute fracture clinic, 77% were given patient initiated follow-up (PIFU), 5% were discharged, 15% were given a follow-up appointment and 2% were admitted from clinic for surgery. In the follow-up fracture clinic, 34% were given PIFU, 29% were discharged and 31% were given a follow-up appointment.

Indications for a further follow-up appointment included a check radiograph (42%), clinical review (26%), cast removal (14%), a wound check or wire removal (5%).

Elective clinic patients

There were 231 patients with scheduled elective clinic appointments. There was a broad case mix including developmental dysplasia of the hip (15%), cerebral palsy (10%) or required follow-up following trauma (10%).

The majority (79.2%), were cancelled, re-scheduled for 3-6 months, offered PIFU or had a telephone consultation with a consultant.

Out of hours work

A total of 39 referrals were made to the on-call paediatric orthopaedic team over the study period. Referrals predominantly came from the BRCH Emergency Department (49%), local minor injury units (26%), or from other hospitals within the Severn region (15%).

All patients referred and seen in the emergency department (ED) were treated as a suspected COVID-19 carrier. Only 4 patients (10%) were suspected of having an active COVID-19 infection due to the presence of a temperature. None of the patients seen presented with a cough. Of those with a suspected active COVID-19 infection, 3 were tested but none returned a positive result.

Conscious sedation in the ED was performed in 60% of patients requiring manipulation. All patients had satisfactory check radiographs post-manipulation and were placed into a Softcast for removal at home. Patients were provided with guidelines specific to the COVID crisis and PIFU.

Surgical activity

From the 16th March – 16th April 2019, 62 elective cases were performed on 19 elective lists. All elective lists in the same period in 2020 were cancelled and re-scheduled. A total of 29 elective cases were scheduled during this period but only 6 (20%) were performed on a designated trauma list.

Trauma operating

From the 16th March – 16th April 2020, 29 cases were performed in total. This included 19 (66%) fracture cases including one open fracture, 4 (14%) infection cases and 6 (21%) urgent elective cases.

Only 9 (31%) of these cases were performed on a designated trauma list. The remaining 19 (66%) cases were performed on a CEPOD list.

The mean time to theatre was 0.54 days (range 0-3 days). The average length of stay was 1.6 days (range 0 – 10).

Of the patients that underwent an operation, a consultant was listed as first surgeon in 6 cases (27%), and as second surgeon in 19 cases (68%). A training grade registrar was listed as first surgeon in 22 cases (79%), and as second surgeon in 5 cases (18%).

For the same month in 2019, 52 cases were performed. There were 35 (67%) fracture cases, 10 (19%) infection cases and 7 (13%) urgent elective cases. The mean time to theatre was 0.97 days (range 0-7 days).

Discussion

The BOASt COVID-19 guidance emphasises the need to manage children with non-operative strategies and minimise outpatient visits, whilst also reducing long-term consequences by prioritising conditions that have immediate permanent morbidity, or lack a practical remedial option1.

We were able to reduce footfall through our hospital by increasing the number of virtual clinic appointments, reducing the number of radiographs taken, reducing admissions by working with ED staff to perform joint relocations and fracture manipulations in the ED, reducing plaster room activity by applying Softcast in the ED and teaching patients how to remove their cast at home. Follow-up appointments were only given if there was a clear indication. The majority of patients were either given PIFU or were discharged.

Whilst there is no doubt that our department has responded well to the guidance in this time of crisis, we do not yet know whether the changes made have been detrimental to patient care. Experiences from one centre with an established virtual paediatric fracture clinic found no ‘serious adverse consequences’ to running such a service at 12 months after its implementation. A saving of £45,000 was made to the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and £106,000 of savings to the hospital.

Despite the allure of reported cost savings without compromising on the standard of patient care, there is a definite need to assess the short- and long-term sequelae of managing these children as we have during the COVID-19 era.

Conclusion

It is possible to run an effective paediatric orthopaedic service that is compliant with the majority of the BOASt COVID-19 guidelines in a busy tertiary referral centre. By reducing clinic, admissions and theatre throughput, we have made a contribution towards protecting our patients and staff.

In conjunction with assessing the safety and efficacy of the service we have provided during this time, we are also looking at the potential sustainability of the changes made to determine whether the economic and environmental cost of delivering our service can be reduced on a long-term basis.

References

- British Orthopaedic Association (2020). Emergency BOASt: Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-boasts-combined.html.

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2020). COVID-19 - guidance for paediatric services. Available at: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-guidance-paediatric-services#footnote1_b2p3o53.

- Robinson PM, Sim F, Latimer M, Mitchell PD. Paediatric fracture clinic re-design: Incorporating a virtual fracture clinic. Injury. 2017;48(10):2101-5.