Early Diagnosis of Pyogenic Spinal Infection

Authors: James Wilson-Macdonald and Nicholas Todd

Download PDFThe incidence of spinal infection is 0.2-2.0 cases / 10,000 hospital admissions and is rising due to factors that predispose to spinal infection, including diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug abuse, spinal instrumentation and medical comorbidities such as hepatic, renal or cardiac failure are becoming more prevalent1-3.

The trilogy of spinal pain, fever and a neurological deficit supports a clinical diagnosis of spinal infection, but patients are often apyrexial or pyrexia is modest. Spinal pain occurs in 67% of patients, motor weakness 52%, fever 44%, sensory abnormalities 40%, and sphincter involvement 27%3. Spinal pain lacks diagnostic specificity. Red flags for spinal infection include: age <20 or >55, pain in recumbency, constant progressive non-mechanical pain, fever, neurological deficit, deformity, thoracic pain, immunosuppressive illness or tenderness to palpation/percussion. Leucocytosis is present in 60% of patients, the white cell count is often only modestly elevated4. The ESR is usually elevated4. The CRP is almost universally elevated5.

Delayed diagnosis occurs in 11-75% of cases6, 7 and is associated with a six times greater proportion of patients with permanent neurological deficit7.

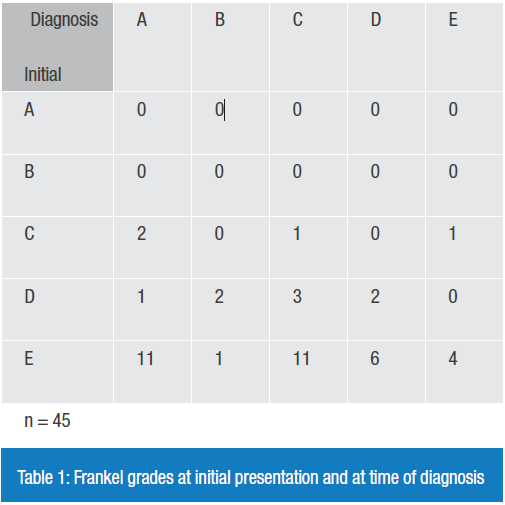

We reviewed the files of 45 litigants with pyogenic spinal infection. Diagnostic delay occurred in 93% of these medico-legal cases with an average delay of nine days. All patients were ambulant at presentation (ASIA C-E). Neurological deterioration occurred in 82%; 31% (14/45) deteriorated to complete motor and sensory paraplegia at final follow-up (ASIA A) (Table 1).

The failures leading to delay in diagnosis and treatment were as follows:

Not to consider differential of infection 23 (51%)

Not to consider thoracic pain as red flag 25 (55%)

No haematology 8 (17.7%)

Not to act on abnormal haematology 29 (64%)

Not to recognise abnormal neurological findings 20 (44%)

Not to act on pyrexia 8 (17.7%)

(N=45)

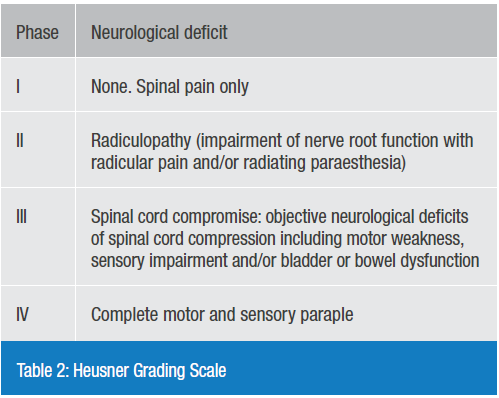

Heusner8 has stratified the clinical findings in pyogenic spinal infection, which is a useful way of stratifying patients and predicting outcome (Table 2). The ideal is to diagnose patients in groups I and II, those in group three have a very poor outcome unless they are treated as an emergency. Once patients progress to group IV, recovery in unfortunately much less likely, and in our study only 2/15 patients made a recovery (from ASIA A to ASIA C and D).

In general, patients with spinal infection and neurological deficit are expected to have a reasonable chance of recovery, for example, in patients with tuberculosis. However, we excluded patients with tuberculosis from this study and we noted that there were very few litigants with tuberculosis, perhaps because they less commonly have a long-term neurological deficit. We noted that the patients with tuberculosis tended to have a better long term outcome.

Early diagnosis prior to a neurological deficit is the ideal. Triage systems based upon risk factors for infection are needed. The CRP should be measured in all suspicious cases, it is almost invariably raised in spinal infection (>50 in 44/45 of our patients, 98%), which confirms an infectious pathology prompting early diagnostic MRI and treatment. The burden to patients and the cost of compensation can be very high where there is a delayed diagnosis of spinal infection.

References

1. Darouiche RO: Spinal epidural abscess, N Engl J Med. 2006; 355: 2012-2020

2. Chen SH, Chang WN, Lu CH, Chuang YC, Lui CC, Chen SF, et al: The clinical characteristics, therapeutic outcome, and prognostic factors of non-tuberculous bacterial spinal epidural abscess in adults: a hospital-based study. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2011; 20:107-113

3. Arko L, Quach E, Nguyen V, Chnag D, Sukul V, Kim BS: Medical and surgical management of spinal epidural abscess: A systematic review. Neurosurg Focus 37(2):E4,2014

4. Soehle M, Wallenfang T. Spinal epidural abscess: clinical manifestations, prognostic factors, and outcomes. Neurosurg 2002; 51:79-87

5. Davis DP, Salazar A, Chan TC, Vilke GM: Prospective evaluation of a clinical decision guideline to diagnose spinal epidural abscess in patients who present to the emergency department with spine pain. Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 2011; 14:765-770

6. Connor DE Jr, Chittiboina P, Caldito G, Nanda A: Comparison of operative and non-operative management of spinal epidural abscess: a retrospective review of clinical and laboratory predictors of neurological outcome. Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 2013; 19:119-127

7. Davis DP, Wold RM, Patel RJ, Tran AJ, Tokhi RN, Chan TC et al: The clinical presentation and impact of diagnostic delays on emergency department patients with spinal epidural abscess. J Emerg Med 2004; 26: 285-291

8. Heusner AP. Nontuberculous spinal epidural infection. N Engl J Med 1948; 239: 845-854

James Wilson-MacDonald is an orthopaedic spinal surgeon working in Oxford. He qualified at Bristol University and undertook a higher degree (MCh) in 1990 on bone growth and remodeling. He trained in New Zealand, France, America, Switzerland and the UK. His main interests include the treatment of scoliosis in children, the management of back pain, spinal trauma, spinal infection and medico-legal issues. He is involved in the development of new treatments for scoliosis in children. He was senior editor of the Trauma section of the Oxford Textbook of Trauma and Orthopaedics. He has a wide experience in medico-legal reporting.

Nicholas Todd was a Consultant Neurosurgeon and Spinal surgeon based at the Regional Neurosciences Centre, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne. He retired from the NHS in October of 2011 and continued in clinical practice privately until April 2015 when he took a break in order to prioritise academic work. Mr Todd has been providing medicolegal reports for over twenty years. He has given evidence in Court on a number of occasions and is currently instructed approximately 60% by Claimant solicitors, 40% by Defendant solicitors.

This article was first published in the March 2019 edition of the JTO.