Caring for patients awaiting orthopaedic surgery

By Bibhas Roy

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Manchester University Foundation Trust

Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Published 26 May 2021

Introduction

Healthcare has long recognised that rules are necessary to equitably distribute medical resources in situations of scarcity1. Various models are described in the recent literature, all require ‘triage’ in some way. This inevitably creates ethical questions and specific policies are necessary.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected global healthcare services, with the potential to overwhelm healthcare infrastructure and resources. Governments have attempted to improve their infrastructures, however, by necessity, concepts of ‘triage’ have been introduced.

Originating from the French verb ‘trier’ meaning ‘to sort’, triage has been used in healthcare primarily in the ‘mass casualty incidents’. This has been extensively used in the military2, but the concepts are also widely used in emergency departments3. It must be remembered that effective triage is a specific skill, and authors have noted that ‘most who write scholarly articles on the subject have never practiced triage, or even witnessed it!’2. It is also important to recognise that demands can create the need to ration medical equipment and interventions4, making concepts of resource allocation necessary for a complete solution.

The three components of triage therefore are sorting, prioritising and allocating resources5. Sorting requires assigning a ranked value or priority to what is being sorted, which leads itself to creation of a prioritisation hierarchy. Resource allocation becomes necessary as the magnitude of the problem increases to an ‘overwhelming’ level. This brings the concepts of ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ implying a shift in decision making from a focus on individual patient outcomes to population-level outcomes. These concepts have been discussed extensively in the literature, with theories of utility described first in the 1700s, along with many other philosophical principles such as the difference principles of justice, principle of equal chance etc6.

In addition, triage does not necessarily conform to modern ‘values’ of medicine such as autonomy – the right of the patient to choose treatment via informed consent, fidelity – the clinician is not always able to act on the best interest of individual patients, etc. There is necessarily a creation of a system that systematically allocates the benefits of healthcare as well as the burden of limited or deferred care within the population.

Response to COVID-19

Institutions and governments at all levels have had to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic with systems considering the above principles.

As the first wave hit, systems were optimised to care for the covid patients, and several governments and institutions cancelled elective surgical procedures7. The cancellation rates for elective non cancer surgery were between 71.2 – 87.4% during the initial 12 week period that followed the WHO announcement in March 20207. It is possible that worldwide, over 115 million operations have been cancelled8. There is now little doubt that elective surgery has restarted in most areas, and policies are in operation to process the procedures safely. There are examples where active surveillance of resource availability and case urgency have been taken into account to develop comprehensive policies9.

NHS Surgical Priority Groups

The Federation of Surgical Specialty Associations (FSSA) Guide was first produced at the request of NHS England at the start of the pandemic. The Guide states that “it is a short-term expedient to the pandemic and not for long term use”. This followed the prioritisation systems (P1-4) already in practice in emergency departments2. It is important to recognise that when evaluating a potential benefit of a treatment to a patient, one is attempting to determine the incremental benefit of that treatment compared with receiving a less resource-intensive or delayed treatment, but rarely does this ever mean no treatment.

Therefore, patients who are deemed to be suitable for waiting specific intervals for their procedure must be clinically reviewed regularly, for purposes of detecting any change in their clinical condition.

Trauma & Orthopaedics

The FSSA prioritisation system is necessary for Orthopaedics to retain comparability with other surgical specialities. It is however recognised that this system is not valid for T&O, especially with respect to the P3 and P4 categories. However, this does map to more familiar systems of clinical prioritisation as demonstrated in prioritisation Table 1.

| Category | Urgency | Timescale |

|---|---|---|

| P1 A | Urgent | <24 hrs |

| P1 B | <72 hours | |

| P2 | Soon | <1 month |

| P3 | Routine | <3 Months |

| P4 | >3 Months |

In addition, it is important to acknowledge that waiting time is an important metric to be taken into consideration for prioritisation, RTT is routinely measured in the NHS, and should not be abandoned.

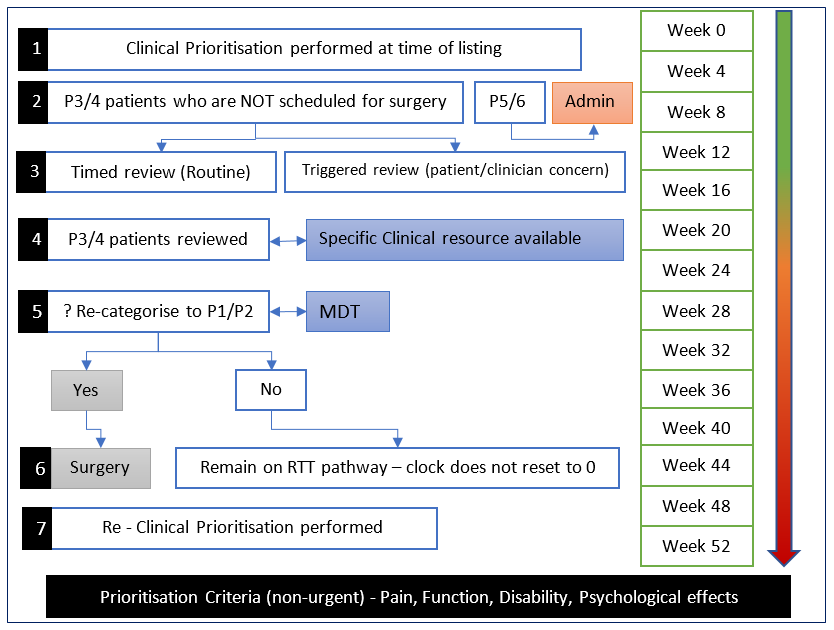

Suggested process flow diagram

We would suggest a process that is more appropriate for our vast group of P3/P4 patients who are frequently deteriorating as they wait and who must be confident that their plight is recognised and important to us.

*The BOA and several specialist societies have recently finalised a position paper on ‘caring for patients awaiting surgery’, which focuses on reviewing and prioritising patients on the current waiting list.

References

- Iserson KV, Pesik N. Ethical resource distribution after biological, chemical, or radiological terrorism. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2003;12(4):455-65.

- Swan KG. Triage: the past revisited. Mil Med. 1996;161(8):448-52.

- StatPearls. 2021.

- Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-55.

- Christian MD. Triage. Crit Care Clin. 2019;35(4):575-89.

- Moskop JC, Iserson KV. Triage in medicine, part II: Underlying values and principles. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):282-7.

- Soltany A, Hamouda M, Ghzawi A, et al. A scoping review of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on surgical practice. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;57:24-36.

- Simoes J, Bhangu A, Collaborative C. Should we be re-starting elective surgery? Anaesthesia. 2020;75(12):1563-65.

- Coleman NL, Argenziano M, Fischkoff KN. Developing an Algorithm to Guide Resumption of Operative Activity in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Ann Surg. 2020;272(3):e236-e239.