The long road to the register: Stories from the Portfolio Pathway

By Jehan Zaiba and Rakesh Johnb

aTrauma and Orthopaedic Consultant, Hywel Dda UHB, West Wales

bTrauma and Orthopaedic Consultant (Upper limb), Macclesfield District General Hospital, UK

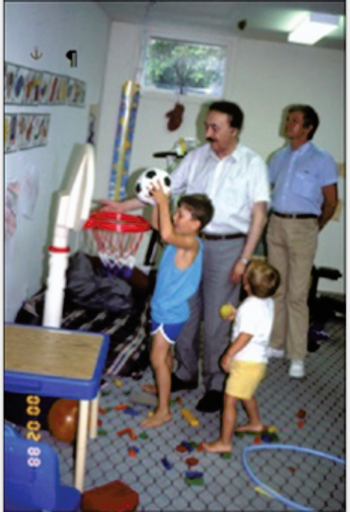

The news of a 10-minute standing ovation for the Kurgan magician reached the western world. This magician, who could fix dreaded infected non-unions or lengthen bones by up to 15cm, had captured global attention. Despite the well-known friction between the Russians and Americans during the Cold War, a US surgeon, accompanied by his pregnant wife and two-year-old son, decided to travel to Europe and the USSR on a fellowship to learn the technique over six months. The first hurdle was, of course, the visa, which is a story for another time. In order to get what he wanted, he learned fresh Italian and Russian and eventually managed to meet the magician himself: Abrahamovich Ilizarov. That young US surgeon was none other than Dror Paley, who brought the Russian knowledge of distraction histiogenesis to the US1.

Illizarov playing with Dror Paley’s children.

Another story of hard work and perseverance is that of a 23-year-old Colombian boy fresh out of medical school who found himself in the US due to the Fidel Castro revolution in his country. With limited resources and uncertain prospects, he arrived in a new country with language barriers, no guaranteed job, and limited recognition of his credentials. He initially worked menial jobs and undertook additional training to meet US standards. He overcame institutional and cultural barriers as an immigrant physician and faced skepticism and academic resistance to his ideas — especially his advocacy for non-operative fracture treatment, which was against the prevailing surgical trend. This is Dr Augusto Sarmiento. I am sure you must have used or heard of his PTB cast for tibial fractures at some point in your career2.

Sarmiento and his autobiography.

Born under Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq, Dr Al Muderis came from a prominent family — his father was a Supreme Court judge with authority in the Marine Corps, his uncle a descendant of Iraq’s royal lineage and a former Prime Minister, and his mother a principled school principal who faced demotion for refusing to join the Ba'ath Party. He attended Baghdad College High School, and went on to study medicine, earning his degree from Baghdad University in 1997. As a junior surgeon at Saddam Hussein Medical Centre in 1999, he was ordered to amputate the ears of army draft evaders — an order he defied after witnessing the execution of a senior colleague who refused. He escaped, hid for hours in a hospital bathroom, and fled Iraq via Jordan and Malaysia, eventually reaching Australia by boat. Detained at the Curtin Immigration Centre and known only as detainee number 982, he endured solitary confinement and hostility before being granted refugee status ten months later. Despite initial struggles, including sending out over 100 job applications, he secured a position at Mildura Base Hospital and later moved to the Austin Hospital in Melbourne, steadily advancing through fellowships and international training to become a respected orthopaedic surgeon and developed the famous ossteointegrated prosthetic limb3.

Professor Munjed Al Muderis.

These are just few stories among hundreds of thousands of immigrant doctors and people who undergo hard work, face subtle or clear discrimination — sometimes personal and sometimes professional — but eventually succeed. They are often seen as a burden or as tools simply there to provide services. Most of them travel to excel in their profession, but only a few are able to cross the sea of obstacles. Very few understand the troubles of their visas, financial burdens, personal and professional needs — and they take all of it on themselves patiently and quietly. But without doubt there are people in their journey who have pointed them in the right direction or given them a helping hand .

Recently, the UK has seen a surge of senior or middle-grade orthopaedic doctors from different countries. There is a common pattern among most of these doctors. I had the opportunity to work with one of them in a Middle Eastern country. He was a very senior surgeon with the skill and talent of a master, calmly tackling complex trauma. I was his resident and he was my consultant. I continued my journey to the UK and became a consultant after some years. He contacted me after a long time to tell me that he had come to the UK to learn complex arthroplasty but is stuck in a registrar job, where he was allowed only very basic trauma work, and that too supervised — which is understandable. I told him that the path to progress includes three options: getting a fellowship (difficult without FRCS), getting into training, or pursuing the Portfolio Pathway. When I explained the amount of paperwork and struggle involved, it felt as if I had broken his back.

One of the ways to get onto the specialist register for people with considerable international experience is by completing paperwork through Portfolio Pathways (PPW) previously known as CESR/Article 14. Apart from the other hurdles we've talked about for IMGs, this is one of the biggest. The paperwork is essentially to show that you are on par with an ST7/ST8 UK trainee who has completed their CCT. Unlike trainees, who get protected teaching and study time, staff grades (mostly IMGs) often cover for trainees during those times. They sometimes have to sacrifice their theatre time when trainees are engaged in teaching — understandably. Another common observation is that no one really takes responsibility for training a staff grade, as they are seen more as a liability. Of course, this is not a general rule; some places are more supportive for staff grades than others.

It is important to understand that the paperwork gathered with all these obstacles will only be valid for experience over the last six years. Staff grades are generally lone riders with self-directed learning and minimal supervision. These are obstacles that are physically and mentally burdensome. Speaking of financial burden, the CCT fee is £497, and the fee for the Portfolio Pathway is £1,902, with a review application (which is often needed) costing an additional £826. Another mental stressor is the time taken by the GMC and the College to manage the process. Just to get a GMC advisor allocated takes 3–4 months. The initial assessment takes a minimum of 3–4 months if there are no revisions. Once accepted by GMC, it is forwarded to the College for another minimum of 3–4 months. On average, an application takes 12–18 months to complete.

As a case presentation, I present to you an interesting case study by my colleague Rakesh John in his own words:

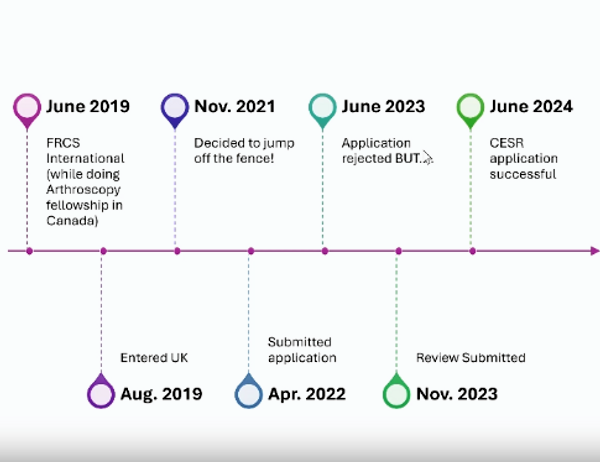

"I completed and passed my training with double post graduate degrees (MS and DNB) from India and did a hip and knee arthroplasty fellowship there. I passed my MRCS in 2016 while doing my registrarship in India. After that, I moved to Nova Scotia, Canada to do a fellowship in arthroscopy and sports medicine. Keeping my knowledge up to date and being aware of the prestige of the FRCS, I took the FRCS International (JSCFE) from Canada and passed in June 2019. With the help of this MRCS and FRCS(Int), I wanted to pursue further training in the UK. Apart from gaining access to the UK, I was absolutely unaware that the exam is mostly to gain nominals and decorate the resume. I entered the UK in August 2019 and despite my previous experience and exams, I was unable to get any good fellowships and mostly had to do registrar jobs. With some guidance from senior colleagues and to open further avenues to gain experience, I decided to seek CESR (alternate path to the specialist register). I had a lot of paperwork and a logbook already sorted, so I submitted my application in April 2022, knowing that it would take a minimum of one-year anyway. In the meantime, because I was already aware that the FRCS International would not be accepted for the application, I decided to sit the JCIE exam and cleared it. In June 2023, I was not surprised when they came back asking for more evidence on trauma experience, audit, and JCIE FRCS. But proactively, I continued to collect evidence during that waiting time, which reduced my time to submission. In November 2023, I resubmitted my application, which was accepted in June 2024."

Timeline of Rakesh John’s journey.

Rakesh John's journey is a long and hard earned success story. He was properly guided for most of his journey and was determined and focused. Rakesh suggests he was fortunate enough to be supported throughout. But there are many stories where there is a severe lack of support and guidance for very experienced people such as Rakesh. They can’t complete their cases in time; their PBAs and CBDs sit in their supervisors’ ISCP for a long time; they find it hard to get rotations in trauma, paediatrics, spine, and hands. Some are unable to engage in managerial and leadership activities due to being new to NHS culture, which stops them from gathering specific evidence in this important area. All of this requires guidance and support from seniors in their departments. Fortunately, some hospitals now have CESR/PPW leads who are working hard to allocate dedicated time and budget to support these professionals.

Even though this alternate route is well documented in guidelines like the SSG and the surgical curriculum, there is still subjectivity and shades of grey, which result in lots of FAQs. The subjectivity and the sheer volume of evidence required (mostly between 1,000 – 1,200 pages) can be intimidating, leading some candidates to procrastinate for a long time. Some lack the clerical abilities to compile and present the evidence in an organised way and, despite having the evidence, are unable to present it properly.

Keeping in view all these problems that I and others have faced, we decided to develop a full one-day course to help people like us. The course was directed towards staff grades, middle grades, LEDs, specialty doctors, and associate specialists working in the UK. The main goal of the course was to inspire and motivate orthopaedic doctors at an intermediate level in the UK to progress in their careers — either by getting into training or by pursuing the Portfolio Pathway.

This online course was organised under the supervision of Professor Enoch (Doctors Academy Cardiff) on 8th February 2025. As the morning session was free, we had international participation from different continents. The morning session consisted of didactic lectures on the structure of training in the UK and the necessary elements to get into training and gather evidence during training. This not only helped candidates aiming for training but also those thinking of submitting their Portfolio applications, as it showed them how to be on par with trainees. One of the lectures, by Vishesh Khanna, presented a case study of how a very experienced surgeon from India got into training and took all the challenges positively — an inspiring story. Krishna Kumar, CESR lead from Cumbria, spoke on 10 mistakes to avoid in a CESR application. The case study of Rakesh John was also presented.

Learning points from one of the talks.

The highlight of the morning session was a talk by Alan Middleton, Hand Consultant and SAC member who regularly assesses applications. He clearly and succinctly explained how the assessment works and what is actually assessed in an application. Candidates were able to ask complex questions in a safe environment, including those about various rotations, acceptable case numbers in case of breaks, submission of WBAs, etc. Alan answered patiently and supportively, without any rush.

The afternoon session was another highlight. There were two arms. In one, Vishesh Khanna led ST3 mock vivas for the upcoming April interviews. There were 20 candidates with a 1:1 faculty-to-candidate ratio. The second arm featured workshops for the Portfolio Pathway, led by four recent successful applicants. Twenty candidates rotated through stations on CV and evidence compilation, audit/QIP and research, WBAs, and communication. We received excellent feedback from the candidates, and everyone benefitted from the course. The fee for the whole day was £65 per candidate.

The historical novel The Physician by Noah Gordon strikes a special chord with me in the present scenario. It follows an English orphan born in 1021 who becomes obsessed with learning real medicine. His journey leads him to Ibn Sina (Avicenna) in Isfahan, Persia, where he studies advanced medical science, disguised as a Jew to avoid Christian persecution. He endures slavery, war, and cultural challenges but witnesses the scientific glory of the Islamic Golden Age. He returns to England to share his enlightened knowledge. The novel champions the courage to cross cultural and ideological boundaries in search of truth and underscores the enduring value of scientific reason over dogma. Truly, the progress of medicine has always depended on openness, humility, and the global exchange of ideas — themes as relevant now as they were a millennium ago.

There is a dire need to invest in our orthopaedic colleagues who wish to be trained and progress but are held back by personal, professional, or social barriers. Regardless of how we perceive them, they will end up treating us or our relatives. If we haven’t invested in them, it’s not just they who suffer — we all do. Most of them are a hardworking and talented bunch, needing only guidance and mentorship. Some actively seek it; others will need us to provide it. And a final message to them from me: No matter how far you fall, if you walk long enough in the dark, the door will open.

References

- Paley, D. (2018). The ilizarov technology revolution: History of the discovery, dissemination, and technology transfer of the ilizarov method. Journal of Limb Lengthening & Reconstruction, 4(2), p.115.

- Sarmiento, A. (n.d.). Bare Bones. Prometheus Books.

- Amnesty International Australia. (2018). From refugee to pioneering surgeon: Munjed Al Muderis. Available at: www.amnesty.org.au/from-refugee-to-pioneering-surgeon-munjed-al-muderis.