A quality improvement journey to optimise antibiotic management and enhance outcomes in paediatric osteomyelitis care

By Colette Revadillo

Final-year medical student, University of Edinburgh

|

This is the winning essay from the 2025 BOA Medical Student Prize Entrants were asked to write a Quality Improvement Project (QIP) and how it has equipped them and their department to perform better. |

Introduction

Paediatric osteomyelitis (OM) is a serious condition that can lead to chronic pain, growth disturbances, and permanent disability1,2. In severe cases, the disease may progress to septic arthritis, systemic sepsis, or chronic osteomyelitis, requiring prolonged antibiotic therapy and surgical intervention3. Such complications impact the child’s quality of life and place a substantial burden on healthcare systems.

Current guidelines from the British Orthopaedic Association Standards for Trauma (BOAST), emphasise the importance of prompt antibiotic delivery to prevent disease progression and complications4. However, several challenges hinder optimal treatment, including difficulties with IV access, missed doses, and inconsistencies in antibiotic prescribing5,6.

This Quality Improvement Project (QiP) aimed to improve antibiotic management in paediatric OM by identifying key areas for improvement and developing structured protocols to enhance patient care. A full Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle was completed to evaluate and refine current practices.

Investigating the problem

A prospective audit was conducted over June–September 2024 to evaluate the management of paediatric osteomyelitis.

Figure 1: Demographics of patients included.

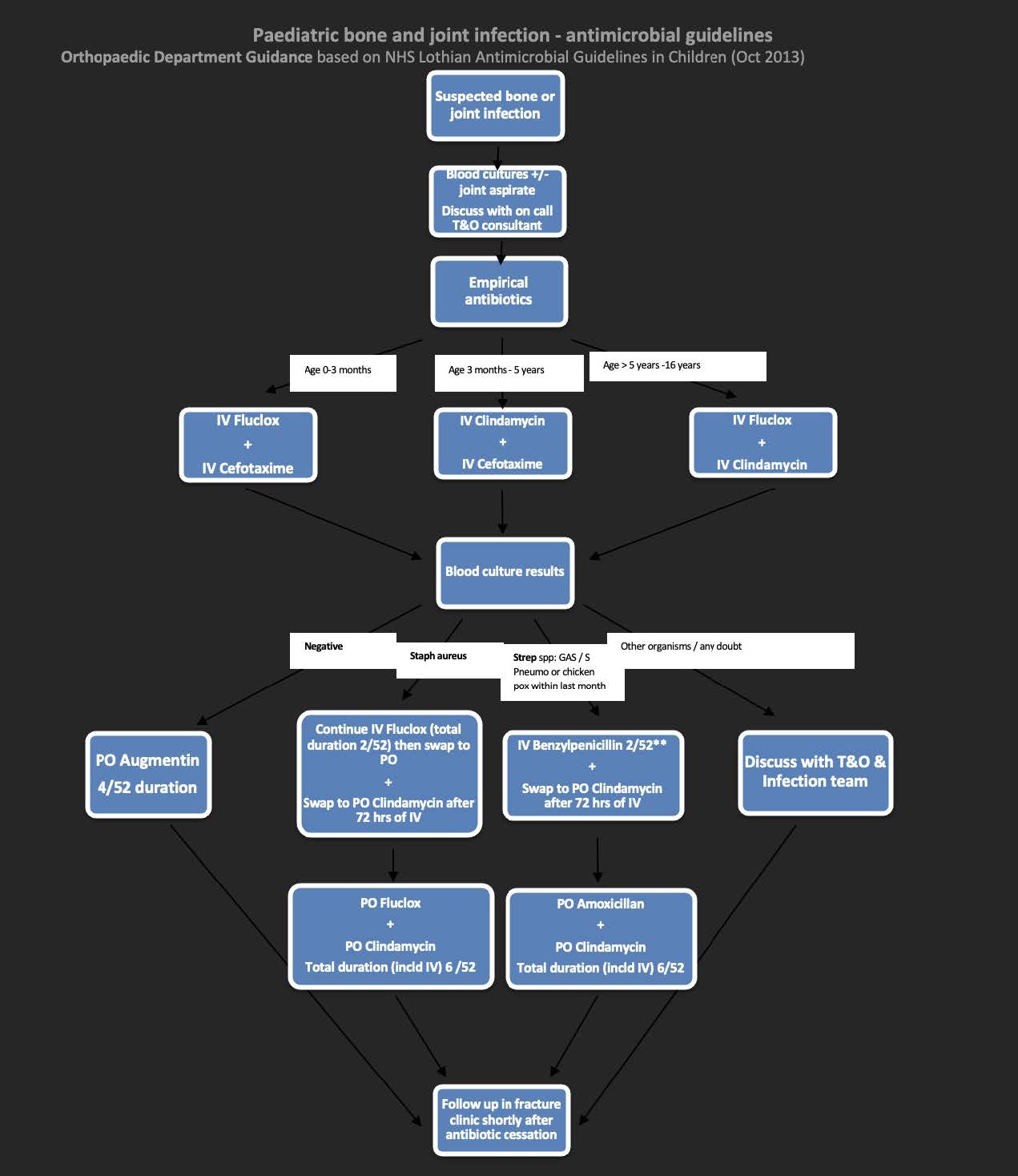

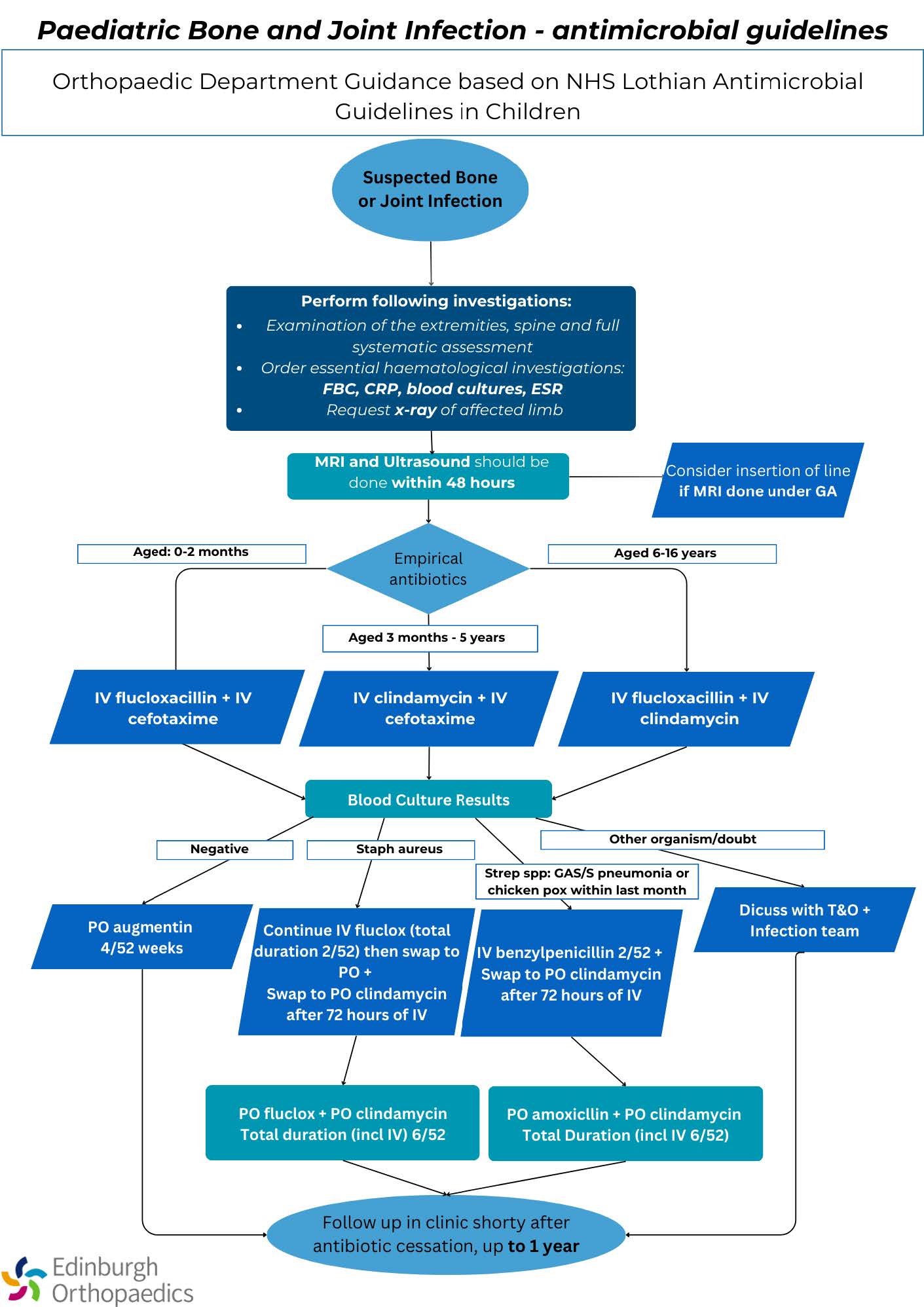

Ten confirmed cases of OM, diagnosed through a combination of radiological evidence (MRI (n=10) and/or x-ray (n=9)) and clinical parameters (raised inflammatory markers or positive radiological evidence) were reviewed. Management was compared against NHS Lothian’s antimicrobial guidelines (Figure 2).

Figure 2: NHS Lothian Paediatric bone and joint infection – antimicrobial guidelines.

Findings

Initial Investigations

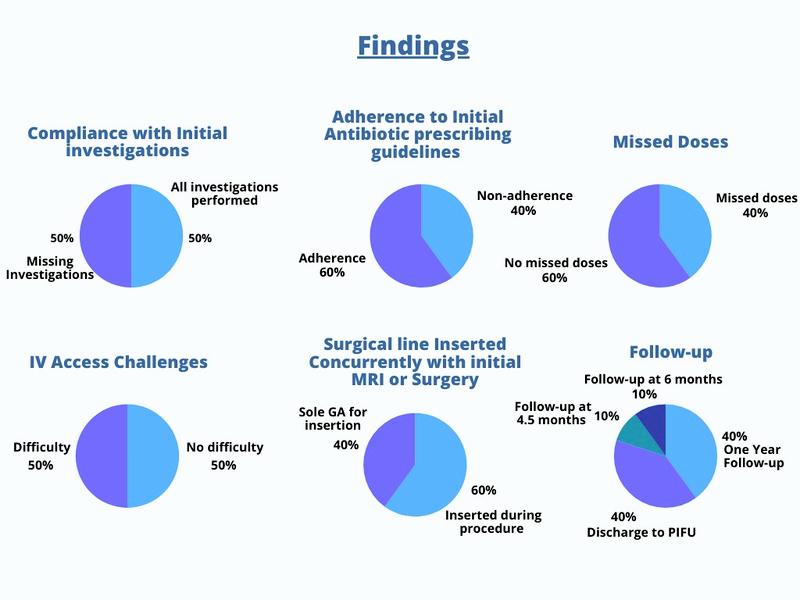

Compliance with initial investigations was suboptimal, with 50% of the patients receiving a full blood count, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), x-ray and blood cultures. ESR was omitted in half of the cases, despite its diagnostic importance, as 40% of patients who initially presented with a normal CRP had an elevated ESR.

Figure 3: Findings.

Antibiotic treatment

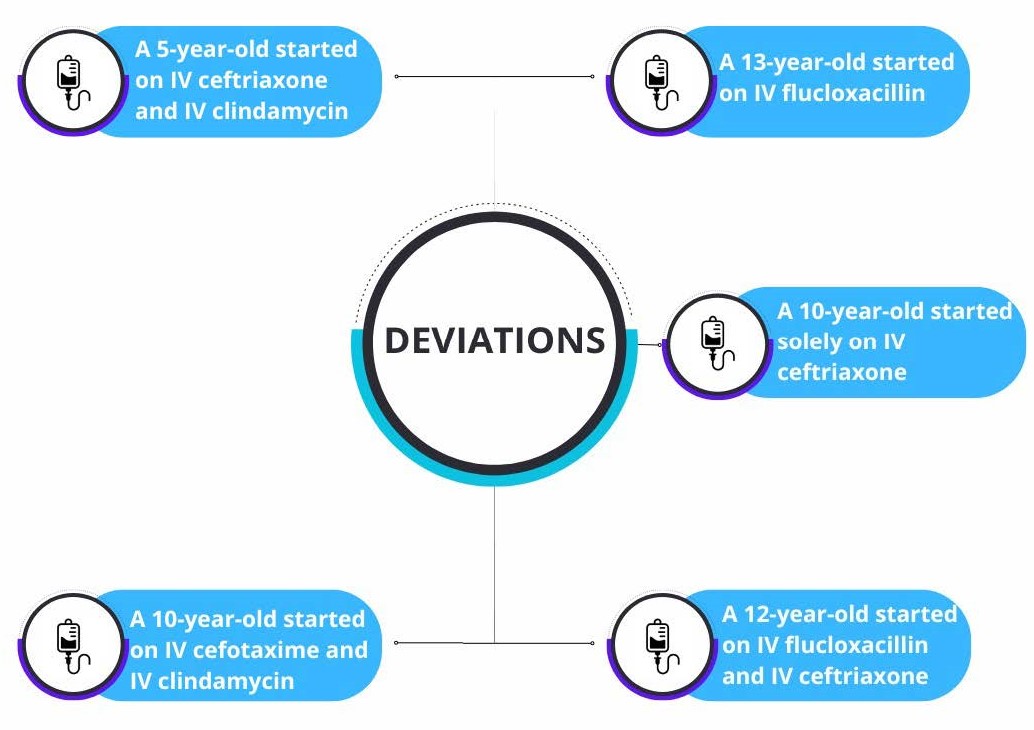

Adherence to antibiotic prescribing guidelines was inconsistent, with only 50% of cases following NHS Lothian recommendations. A common deviation was prescribing ceftriaxone in older children instead of the recommended flucloxacillin-clindamycin combination, highlighting a lack of clarity in age-specific prescribing (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Deviations from antimicrobial guidelines.

Intravenous access

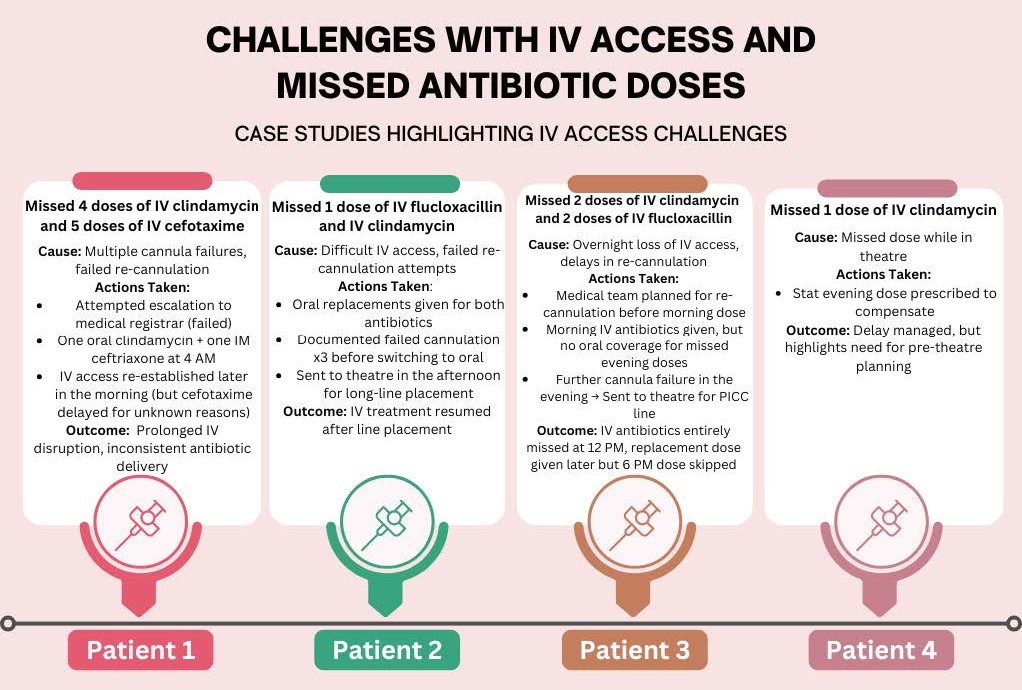

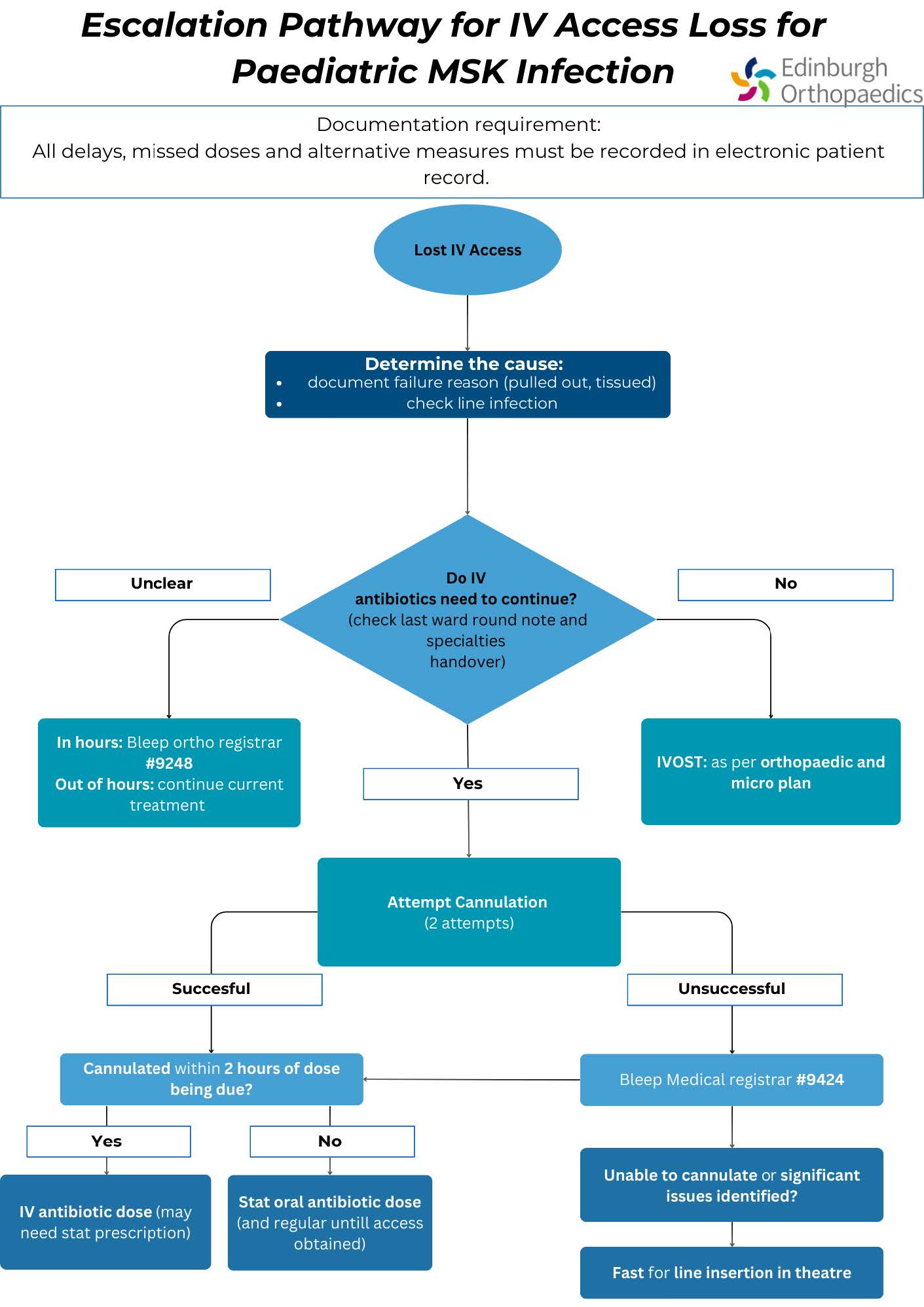

Securing IV access proved to be a significant challenge, with 50% of patients experiencing difficulties, leading to missed antibiotic doses in 40% of cases (Figure 5). Only one patient received timely oral antibiotics as compensation for missed IV doses, highlighting the need for an escalation pathway to promptly address such issues.

Figure 5: Details of missed doses.

Despite these challenges, 60% of patients undergoing surgery or MRI under general anaesthesia had a surgical line inserted concurrently, reducing the need for additional procedures. However, the remaining 40% required general anaesthesia solely for line insertion, suggesting an opportunity to standardise this practice to minimise unnecessary interventions.

Creating solutions

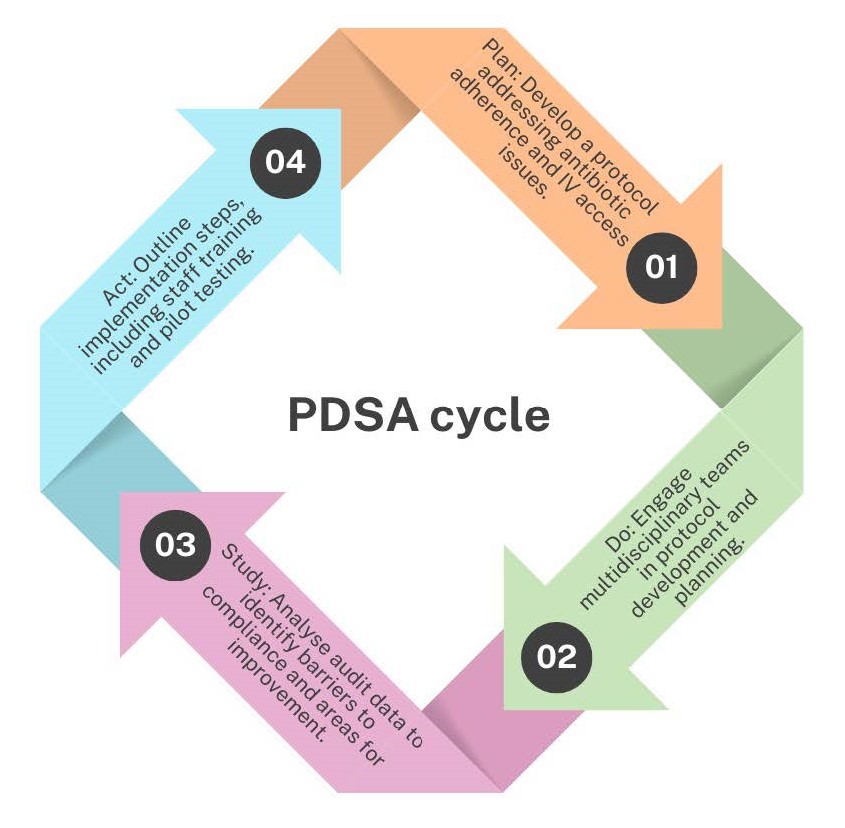

The first PDSA cycle was completed, focusing on the planning and analysis phases. Solutions targeted four key areas: refining antibiotic guidelines, improving IV access planning, establishing a clear escalation pathway for missed doses, and standardising diagnostic protocols (Figure 6).

Figure 6: PDSA cycle.

1. Refinement of antibiotic guidelines + standardised diagnostic protocol:

To ensure accurate and timely diagnosis, standardised diagnostic protocols were implemented alongside refined antibiotic guidelines (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Refinement of guidelines

ESR and blood cultures were made mandatory at initial presentation. While obtaining these tests in a busy emergency setting poses challenges, their inclusion is essential for confirming OM, identifying causative pathogens, and tailoring treatment. Adjustments to age brackets in antibiotic guidelines were also made to improve prescribing clarity. Further measures, including reinforcing the importance of dual therapy, discouraging inappropriate monotherapy, and providing targeted clinician education, are necessary to minimise prescribing errors and improve adherence to best practices.

2. Proactive IV access planning

To mitigate IV access difficulties, a proactive protocol is being developed in collaboration with the anaesthetic team. This recommends inserting peripherally inserted central catheters during initial surgical or imaging procedures under general anaesthesia, thereby reducing the need for repeated cannulation attempts, minimising patient distress and

improving treatment continuity.

3. Escalation pathway for IV access loss

An escalation pathway was introduced to ensure timely intervention and minimise missed antibiotic doses. Delays in securing IV access were a significant barrier to effective management, necessitating a structured approach to address these issues promptly (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Proposed escalation pathway for IV access loss.

Challenges and limitations

Challenges included the complexity of coordinating multiple departments involved in paediatric OM management. Collaboration between emergency medicine, orthopaedics, paediatrics, infectious diseases, microbiology, and anaesthetics was crucial but posed logistical difficulties.

The small sample size of ten cases also limited the generalisability of findings, necessitating further data collection to strengthen the evidence base for proposed interventions.

Impact and future directions

The impact of these interventions has set the foundation for long-term improvements in paediatric OM management. The revised antibiotic guidelines provide clarity and reduce prescribing errors, while the implementation of proactive IV access planning and structured escalation pathways enhances treatment continuity and reduces missed doses.

Future directions for this project include evaluating the potential of early high-dose oral antibiotic therapy as an alternative to IV treatment. Recent evidence suggests that oral antibiotics may be equally effective, thereby reducing IV-related complications, hospital stay duration, and healthcare costs7.

Conclusion

This QiP identified critical areas for enhancing paediatric osteomyelitis management, including improving adherence to antibiotic guidelines, optimising IV access strategies, and establishing structured escalation pathways for missed doses. The revised protocol simplifies antibiotic prescribing, reduces confusion, and improves compliance, while proactive IV access planning minimises patient discomfort and treatment interruptions. These changes not only enhance patient outcomes but also streamline departmental workflows, aligning with BOAST guidelines and national standards.

Personal reflections

Beyond its clinical impact, this QiP has been a transformative learning experience for me. It deepened my understanding of the complexities involved in implementing change within a clinical setting and underscored the importance of collaboration in driving sustainable improvements. Observing the interplay between clinical practice, research, and guideline development reinforced the value of evidence-based decision-making and multidisciplinary

teamwork.

Through this project, I developed essential skills in audit design, stakeholder engagement, and data analysis, which will inform my future contributions as a clinician.

References

- Johnston JJ, Murray-Krezan C, Dehority W. Suppurative complications of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in children. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B. 2017;26(6):491-6.

- Peltola H, Paakkonen M. Acute osteomyelitis in children. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:352-60.

- Momodu II, Savaliya V. Osteomyelitis. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532250.

- British Orthopaedic Association. BOASt guidelines: The management of children with acute musculoskeletal infection. Available from: www.boa.ac.uk/resource/boast-the-management-of-children-with-acute-musculoskeletal-infection.html.

- Dhochak N, Lodha R. Difficult Intravenous Cannulation in Children: Role of Assisting Devices. Indian J Pediatr. 2023;90(6):533-4.

- Naik VM, Mantha SSP, Rayani BK. Vascular access in children. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(9):737-45.

- Bybeck Nielsen A, Borch L, Damkjaer M, Glenthøj JP, Hartling U, Hoffmann TU, et al. Oral-only antibiotics for bone and joint infections in children: study protocol for a nationwide randomised open-label non-inferiority trial. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6):e072622.