Getting it right from the front door: Introduction of a trauma admission proforma

By Anna Jones

5th year medical student, Cardiff University

|

This is a runner-up essay from the 2025 BOA Medical Student Prize Entrants were asked to write a Quality Improvement Project (QIP) and how it has equipped them and their department to perform better. |

Background and aim

An admission clerking, which serves as the first documented encounter with a patient, is often the most thorough history that will be documented and hence is frequently relied upon throughout the admission. As outlined by national guidelines set by the GMC and RCS, legible and comprehensive documentation provides the basis for safe clinical practice1,2. In orthopaedic trauma patients, a poorly documented clerking can have a direct impact on patient outcomes and decision/time to surgical intervention3. A well-written entry may improve efficiency during ‘post-take’ ward rounds and crucially, as a medico-legal document, function as evidence in cases of litigation4,5. Despite this, there is huge variation in documentation quality6 and in the Royal Glamorgan Hospital there is no proforma augmenting the problem. A growing body of research suggests standardised proformas not only improve patient outcomes but are preferred by clinicians and serve as examples of 'best practice' to newly qualified doctors3,7-10.

PDSA cycle 1

This study took place at Royal Glamorgan Hospital, a District General Hospital in Rhondda Cynon Taf. Prior to this study, a proforma was in place for patients with Neck of femur (NOF) fractures only; clerking for all other patients was free hand – making them difficult to identify and locate as well as varying hugely in quality. A consultant-led team designed and implemented a Trauma Admissions Proforma, with subheadings for criteria deemed relevant. This change was introduced at a clinical governance meeting. One week’s worth of trauma admissions notes was collected prior to and following the intervention.

Results

39 admissions notes were collected overall: 20 in August 2024, prior to proforma introduction and 19 in February 2025 post. Without a proforma, medication lists, allergy status, lifestyle habits and cognition were rarely recorded. Smoking status, which is known to impair post-operative wound healing11,12 was recorded only 28% of the time. Just 17% of admissions included the name of the supervising consultant.

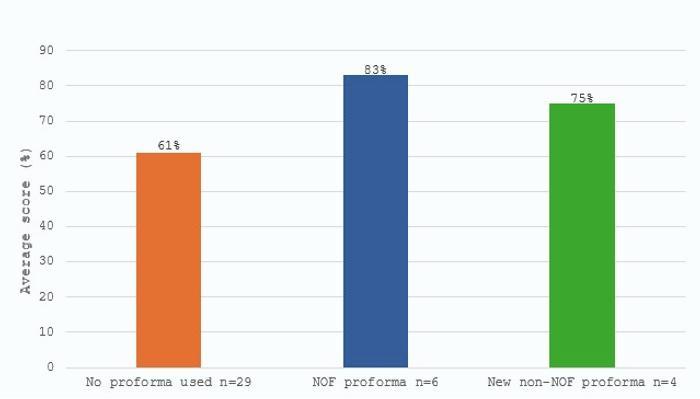

Figure 1: Average scores of admission notes, scored out of all 23 criteria outlined in the new proforma.

Surprisingly, compliance to the new proforma was poor: of the 19 admission notes collected during the second audit, only four used the proforma. Despite this, it appears that the new proforma aided in providing a more comprehensive social history. Smoking status was included 75% of the time and mobility and care arrangements both 100%. These were previously included 50% and 39% of the time. Overall, documentation improved in 13 of the 23 criteria compared to where no proformas were used during the first audit. When individual admission notes were assessed for completeness, we found that both proformas – NOF and non-NOF – scored higher on average than freehand notes (83% and 75% compared to 61%).

It is perhaps no coincidence that the areas which failed to improve, even with a new proforma in place, were also the most time-consuming to document. The task of re-writing a medication list in an elderly multimorbid patient, for example, is an arduous one and consequently most (75%) left the box blank, opting instead to note 'see drugs chart'. The same could be said for VTE prophylaxis: there was no significant difference in compliance between freehand notes and the new proforma (28% compared to 25%).

Not a single admissions clerking from the study took note of hand dominance, most likely due to the admissions consisting mainly of lower limb injuries.

|

|

% compliance (1st audit) |

% compliance (2nd audit) |

|||

|

|

No proforma used (n=18) |

NOF proforma used (n=2) |

No proforma used (n=11) |

NOF proforma used (n=4) |

NEW non-NOF proforma (n=4) |

|

Date |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Time |

94 |

100 |

100 |

75 |

100* |

|

Consultant |

17 |

100 |

9 |

100 |

100* |

|

Clerking doctor |

89 |

100 |

100 |

75 |

100* |

|

PC |

94 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100* |

|

HPC |

94 |

100 |

91 |

100 |

100* |

|

Past medical history |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Medication list |

56 |

100 |

0 |

25 |

25 |

|

Allergies |

50 |

50 |

45 |

100 |

75* |

|

SH: Lives with |

61 |

100 |

73 |

100 |

100* |

|

SH: Smoking |

28 |

100 |

36 |

75 |

75* |

|

SH: alcohol |

22 |

100 |

36 |

75 |

75* |

|

SH: care arrangements |

39 |

100 |

55 |

100 |

100* |

|

SH: mobility |

50 |

100 |

73 |

100 |

100* |

|

SH: hand dominance |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Observations |

39 |

100 |

73 |

50 |

25 |

|

Examination findings |

94 |

100 |

91 |

100 |

75 |

|

AMT/ cognitive screen |

11 |

100 |

55 |

75 |

25* |

|

Bloods |

83 |

100 |

45 |

75 |

75 |

|

Imaging |

61 |

100 |

55 |

100 |

50 |

|

VTE prophylaxis |

28 |

100 |

0 |

25 |

25 |

|

Plan |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Senior review |

56 |

0 |

100 |

100 |

100* |

Table 1: Table illustrating the inclusion of data deemed relevant in an orthopaedic trauma clerking. (*) denotes an improvement in compliance compared to when no proformas were used during the 1st audit.

Limitations, lessons learned and possible improvements

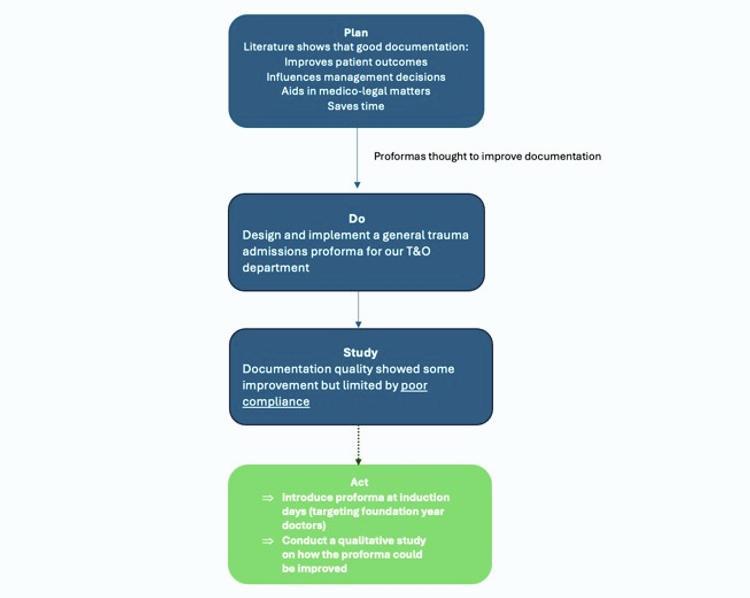

This was a useful study. However, several limitations were highlighted. Given the small sample size and low levels of compliance to the proforma, it was not feasible to utilise significance tests. The data also fails to account for instances where investigation results had not yet been received. Nevertheless, the trends in this study suggest that the new proforma has the potential to outperform freehand admission notes in quality and completeness. This is in line with the current literature3,7-10. Moreover, this first PDSA cycle elucidated several factors which may have interfered with proforma compliance. The responsibility of writing admission notes falls mainly on foundation year doctors and senior house officers. As such, when the proforma was introduced at a governance meeting - attended mainly by consultants, registrars and staff-grade doctors – our key demographic was not targeted. It is therefore possible that many were unaware that this resource was available.

Furthermore, given the nature of foundation training, which requires resident doctors to rotate every four months, our initial cohort had already moved on to other specialties. This inevitably makes it difficult to enact permanent changes. Introducing the proforma during induction days could mitigate this problem and ensure standards are upheld.

Finally, while proformas can act as useful guides, the decision of whether to fill in the boxes lies ultimately at the clerking doctor’s discretion, and this was also noted by Ehsanullah et al.9. We observed that the most time-consuming elements of the proforma – medication lists, cognitive assessments and VTE risks – were often left blank. This could be rectified by conducting a survey of how clerking doctors feel about the proforma and ask for feedback on how it can be made more convenient to use.

Figure 2: A comprehensive summary of our complete PDSA cycle.

Conclusion

In line with current research, our study demonstrated that the use of a standardised proforma makes for a more detailed and robust admissions clerking. We have made a substantial and significant change with the introduction of this proforma, seen by increased documentation of living arrangements, care arrangements and living circumstances, all of which are essential to consider in surgical patients. However, compliance proved to be a limiting factor. Our plans include promoting awareness of the proforma amongst foundation year doctors, ensuring the proforma can be easily found on hospital wards, and evaluating its ease of use.

References

- GMC. Good Medical Practice 2023. Available from: www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice-2024---english-102607294.pdf.

- RCS. Good surgical practice section 1.3 2013. Available from: www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/Files/RCS/Standards-and-research/Standards-and-policy/Good-Practice-Guides/New-Docs-May-2019/RCS-_Good-Surgical-Practice_Guide.pdf.

- Faraj AA, Brewer OD, Afinowi R. The value of an admissions proforma for elderly patients with trauma. Injury. 2011;42(2):171-2.

- Rtiza-Ali A, Houghton CM, Raghuram A, O’Driscoll BR. Medical admissions can be made easier, quicker and better by the use of a pre-printed Medical Admission Proforma. Clinical Medicine. 2001;1(4):327.

- Lyons JM, Martinez JA, O'Leary JP. Medical Malpractice Matters: Medical Record M & Ms. Journal of Surgical Education. 2009;66(2):113-7.

- Baigrie RJ, Dowling BL, Birch D, Dehn TC. An audit of the quality of operation notes in two district general hospitals. Are we following Royal College guidelines? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76(1 Suppl):8-10.

- Jonathan K, Amy F, Sophia T, yahya h, Alicja F. The use of a pro forma to improve quality in clerking vascular surgery patients. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports. 2016;5(1):u210642.w4280.

- O'Driscoll BR, Al-Nuaimi D. Medical admission records can be improved by the use of a structured proforma. Clin Med (Lond). 2003;3(4):385-6.

- Ehsanullah J, Ahmad U, Solanki K, Healy J, Kadoglou N. The surgical admissions proforma: Does it make a difference? Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2015;4(1):53-7.

- Hannan E, Ahmad A, O’Brien A, Ramjit S, Mansoor S, Toomey D. The surgical admission proforma: the impact on quality and completeness of surgical admission documentation. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -). 2021;190(4):1547-51.

- Fan Chiang YH, Lee YW, Lam F, Liao CC, Chang CC, Lin CS. Smoking increases the risk of postoperative wound complications: A propensity score-matched cohort study. Int Wound J. 2023;20(2):391-402.

- Rozinthe A, Ode Q, Subtil F, Fessy M-H, Besse J-L. Impact of smoking cessation on healing after foot and ankle surgery. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. 2022;108(7):103338.