How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected junior doctor training? A survey analysis

By Andrew P Dekker, D, Danielle M Lavender, David I Clark, Amol A Tambe

Department of Trauma & Orthopaedic Surgery, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Published 15 June 2020

Introduction

On March 11th 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, also known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic1. This also represented a major incident for the National Health Service (NHS) given the serious threat to the health of the community and large numbers of critically unwell patients requiring hospital admission for ventilatory support2, and on 30th January 2020 NHS England declared a Level 4 National incident3.

National guidelines from NHS England4 have provided a framework for the redeployment of our workforce and changes in clinical management of emergency and routine conditions during this crisis.

Reflective learning from major incidents is critical and improves our preparedness and subsequent ability to recover faster from future events5.

COVID-19 has been shown to have a significant impact on the emotional and psychological health of medical staff6-8 and to risk worsening of pre-existing mental health problems9.

A survey is an appropriate tool to investigate emotion and opinion10 and rapidly collect knowledge and experiences from this unprecedented event11,12. Although recent surveys looking at impact on mental health have been performed6,8, to our knowledge no prior survey gathering information on the impact of COVID-19 on training and redeployment is available in the published literature.

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on junior doctors training and perceptions of their experiences during the pandemic.

Materials and methods

An electronic survey (Google forms) was performed between 1st May 2020 and 1st June 2020. The survey was distributed by email to all doctors in training including foundation trainees, core surgical trainees, registrar and junior and senior clinical fellows within a single NHS Trust. The survey format was totally anonymised and confidential.

Questions were asked relating to grade and clinical area, redeployment, shift pattern, mental health, effect on training, communication, personal protective equipment and learning points from the experience.

Responses were analysed by two main groups; those not redeployed to another clinical area, and those doctors redeployed to another clinical area.

Results

60 Doctors responded in total; 31 foundation trainees, three core surgical trainees, 17 registrars, three junior clinical fellows and six senior clinical fellows. Doctors were from all medical and surgical specialties: acute medicine (1); critical care (3), emergency medicine (1), ear, nose and throat surgery (3), general practice (1), general surgery (3), general practice (3), general medicine (11), neurosurgery (1), obstetrics and gynaecology (4), paediatrics (3), trauma and orthopaedic surgery (25), urology (1).

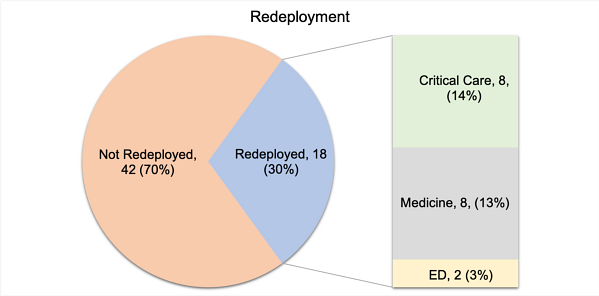

Of these, 18 (30%) were redeployed to another clinical area and 42 (70%) were not, (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pie chart showing redeployment of doctors. ED = Emergency Department.

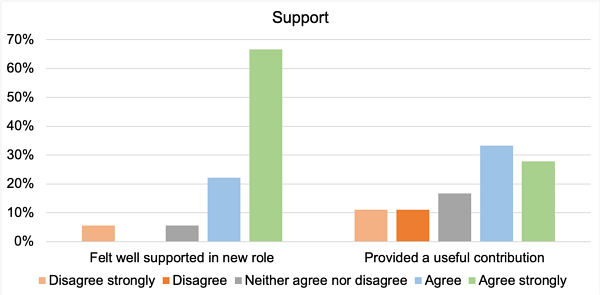

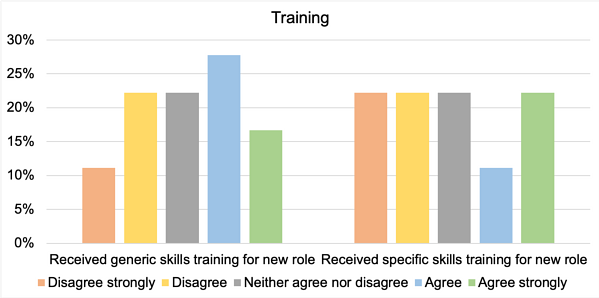

All redeployed doctors were supervised by consultants. Those redeployed generally felt well supported and that they were providing a useful contribution, (Figure 2). The level of training before redeployment was considered mixed, (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Bar chart showing support for redeployed doctors.

Figure 3: Bar chart showing training for redeployed doctors.

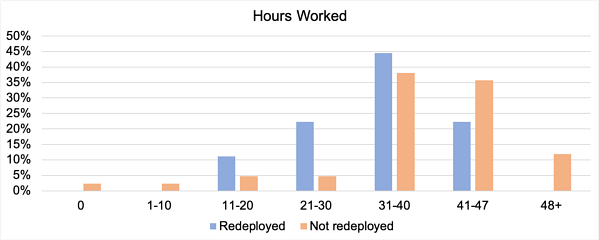

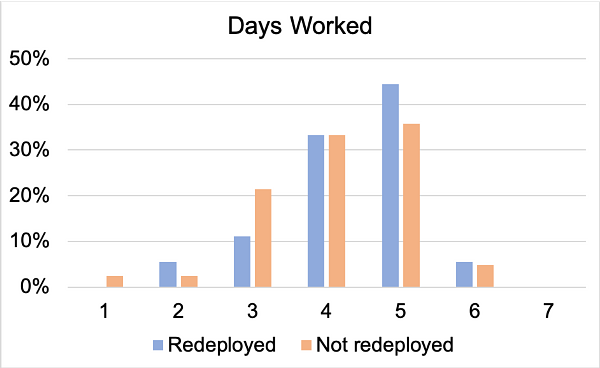

The median hours worked was 31-40 hours in both groups, (Figure 4), and the median days worked per week was four in those not redeployed and 4.5 in those redeployed, (Figure 5). Five doctors reported working in excess of 48 hours per week; all had not been redeployed and were working in psychiatry, obstetrics and gynaecology, general surgery, trauma and orthopaedic surgery. All were junior grade (foundation, junior clinical fellow, senior house officer) and all felt burnout. Three doctors reported working an average six days per week.

Figure 4: Bar chart of hours worked for redeployed and not redeployed doctors.

Figure 5: Bar chart of days worked for redeployed and not redeployed doctors.

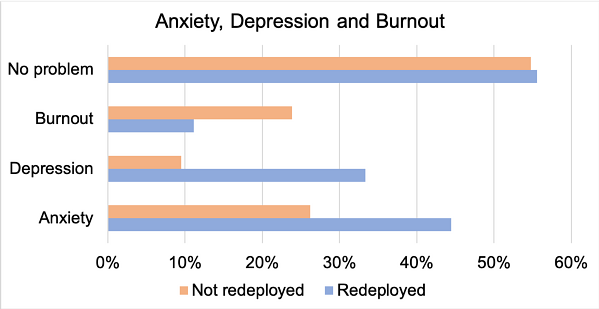

A high incidence of anxiety, depression and burnout (45% overall) was seen in both groups, (Figure 6). Burnout was more common in those not redeployed (24%) than those redeployed (11%).

Figure 6: The incidence of anxiety, depression and burnout.

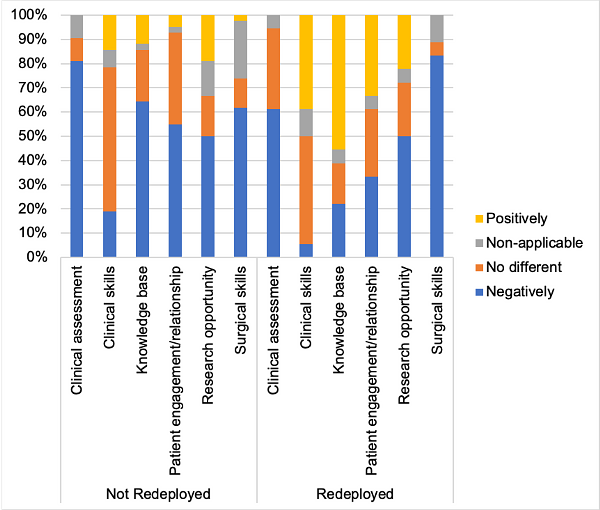

While surgical skills seemed to have been impacted in a prominent manner across both groups, over 70% of the junior doctors felt their clinical skills were not negatively impacted, (Figure 7). Research was impacted negatively across both groups equally. Overall the redeployed group had a more positive experience with respect to clinical skills and knowledge base.

Figure 7: Bar chart of the effect on training for redeployed and not redeployed doctors.

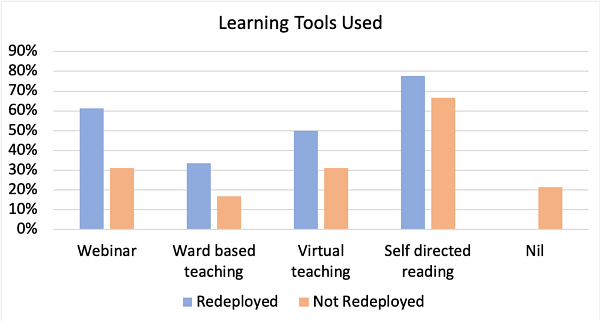

The use of learning tools was lower across all categories in those not redeployed, with 21% of those not redeployed using no learning tools. All redeployed doctors used learning tools, (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Bar chart of learning tools used for redeployed and not redeployed doctors.

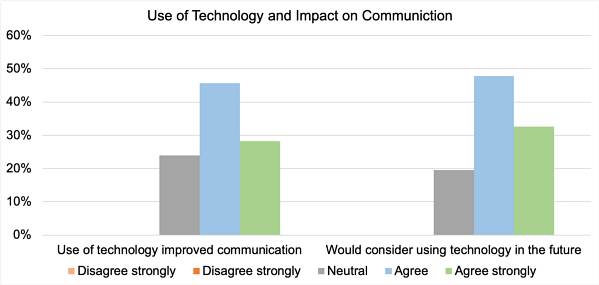

Electronic teamworking applications such as ‘Microsoft Teams’ were used by 83% of redeployed and 74% of not redeployed doctors since the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of teamworking applications was felt to improve communication and doctors felt they were likely to use the technology in the future, with no negative responses, (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Bar chart for the use of technology and the impact on communication for all doctors.

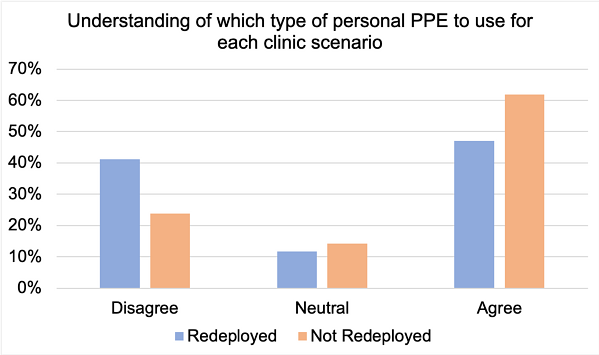

58% of doctors felt they understood which type of personal protective equipment (PPE) to use for different clinical scenarios, (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Confidence in the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) to be used for redeployed and not redeployed doctors.

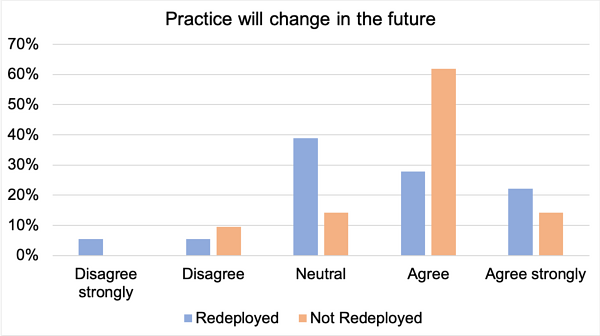

The overall impact on change of clinical practice for the future was significant, with 68% of doctors responding agree or agree strongly, (Figure 11).

Figure 11: The overall impact on change of clinical practice for the future for redeployed and not redeployed doctors.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on all aspects of clinical work. This survey has revealed the impact on training and wellbeing for junior doctors.

Nearly one third of respondents were redeployed to another clinical area; mainly medicine and critical care. Training in new clinical areas brought its own challenges and the feedback from responders indicates that there was some initial uncertainty of role and requirements. The fluctuating level of demands on the department meant at times some doctors felt they were not required.

Many hospital trusts entered the COVID-19 period with a sense of urgency in up-skilling their staff and facilities to deal with a potential mass influx of unwell COVID-19 cases. This meant that training opportunities had to be provided within fairly short timeframes. This is reflected in the responses received. Many doctors took the opportunity to gain skills and knowledge from the new clinical area when not directly involved in caring for patients and ward-based training especially from critical care consultants was rated very highly. A similar experience of improving clinical skills and knowledge by gaining further experience managing critically unwell patients whilst redeployed during the COVID-19 pandemic was reported by Gonzi et al.13.

100% of those redeployed to another area had the benefit of direct consultant led supervision; this demonstrates that despite the pressures on the system, consultants were accessible and provided appropriate support and advice as required. This was especially relevant in the critical care areas.

One third of redeployed doctors felt there was room for improvement in the generic or specialty training provided prior to redeployment; despite this however, the overwhelming majority of doctors felt well supported in their roles and valued in their contribution to the department.

This highlights a key learning point in planning ahead for future major incidents or pandemics with specialty specific training programmes prepared in advance and ready to be activated. Junior doctor training may benefit from the integration of major incident training to help prepare for future events. Keeping the workforce up to date with mandatory training to ensure generic skills are preserved would also prevent anxieties about shortfalls in generic skills. A prepared emergency rota template with stages of redeployment with stepwise escalation depending on the severity of the incident would be another way to lessen the workload in the acute response phase and reassure doctors of the plan going forward. The importance of the development of strategies to deliver training whilst adhering to social distancing was emphasised by Bakewell et al. who suggested adapting training in real time and keeping abreast of national guidance by delivering policies at the trust management level to harmonise local decision-making and facilitate essential training14.

As the crisis eased, doctors were appropriately stood down from redeployment when it was recognised their presence was no longer required and almost all doctors in both groups worked less than six days of the week and less than 48 hours per week.

National guidelines from Public Health England were evolving during the survey period as more research was provided on this novel disease. The hospital trusts had to quickly respond to the rapidly changing national advice with regard to PPE. Different departments also had their own risk assessments and produced area and specialty specific advice; therefore it is not surprising that 42% of respondents had some anxiety or uncertainty about which PPE to wear for each clinical situation.

Effective communication and maintaining physical distancing was a key issue as the pandemic progressed. Communication of rota changes using technology (Microsoft Teams) was well received and a junior doctor group electronic messaging group via a mobile phone application facilitated rapid feedback on required changes as the crisis evolved. Our impression is that these technologies have had a major impact on how we effectively work and communicate during the current pandemic and the benefits felt will influence clinical interaction going forward.

Consistent with recent studies6,8, our cohort of junior doctors reported a considerable impact on mental health with 70% of the respondents reporting anxiety, depression or burnout. Recommendations to mitigate this include training in psychological skills of medical staff6. Such training was not specifically assessed in this study however a trust ‘virtual wellness group’ had been put in place by the trust already. Some junior doctors reported accessing this on Microsoft Teams.

Feedback from responding doctors was that a positive attitude, managing expectations and accepting the unprecedented crisis to the healthcare system, being ready to adapt to a changing environment and demands were common coping strategies. These attributes are commendable and show that the junior doctor / workforce were realistic about their situation and despite common anxieties developed insights and coping mechanisms that no doubt helped them through the peak period of the pandemic. Using technology to keep connected to friends and family was also helpful.

Many doctors indicated that they had taken up more exercise to help with their wellbeing. Exercise is an established effective method to reduce depression and anxiety15 and in particular running has been proven just as effective as psychotherapy in alleviating symptoms of depression16.

The workplace changes had a significant effect on training, with surgical skills most negatively impacted, attributable to the cessation of elective surgical procedures and most emergency procedures being led by consultant teams.

Clinical skills were generally not adversely affected. Knowledge was adversely affected in those not redeployed however those redeployed reported a positive impact on knowledge which can be attributed to teaching provided in the new clinical area and initiative to self-educate with webinars and reading to perform well whilst redeployed. While surgical skills seemed to have been impacted in a prominent manner across both groups, over two thirds of junior doctors felt that their clinical skills were not negatively impacted. Continued clinical engagement is key to maintain junior doctor engagement across the spectrum of clinical activities despite the changing clinical environment. Research was impacted negatively across both groups.

Use of learning tools differed greatly between the two groups. All redeployed doctors employed some form of tool to advance their knowledge, with over half undertaking virtual teaching and webinar. 21% of those not redeployed did not use any learning tools and although some used virtual learning platforms, their use was much more limited. Feedback has shown that those taking initiative towards directing their own training had a more positive experience.

The use of technology for the improvement of communication and teamwork has been developing in the modern era with known benefits17 but has proven invaluable in order to adhere to social distancing guidelines and permit working from remote locations such as home. This has had clinical, educational and research applications. Respondents using technology have been able to further their academic goals and mitigate lost training opportunities. Doctors using webinar, virtual learning platforms such as Zoom, Skype and Microsoft Teams reported a better ability to keep knowledge up to date and retain a feeling of advancing training. Technology enabled virtual clinical and academic meetings allowed attendance whilst maintaining social distancing, which was often also more convenient than meeting in person. This shows the importance of evaluating the changes in practice put in place during major incidents, to identify those innovations that will be valuable to implement long term.

Overall, non-redeployed doctors were more likely to feel burnout, and less likely to report positive impacts on training than their redeployed counterparts. This suggests that the personal and professional development consequences were at least as substantial for those not redeployed, despite their lower workload and unchanged clinical area.

Ultimately the majority of doctors felt that their practice would change in the future as a result of the experience. Doctors felt reflective practice has helped them learn from this experience and recommended being proactive and taking on leadership roles.

This study had limitations including that they total number of recipients was unknown therefore a response rate could not be calculated. The rates of anxiety, depression and burnout before the COVID-19 pandemic were unknown and to retrospectively survey this was considered unreliable, therefore the impact of COVID-19 on mental wellbeing cannot be fully determined. Data on hours worked and training undertaken was entirely self-reported and not verified.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on clinical practice, training and mental health; however, these can be mitigated by taking the initiative to learn from this unique experience and make use of novel training opportunities, especially through technology. Preparedness for future episodes that impact or affect the health care systems in a major fashion is a key issue. To ensure that junior doctors feel confident in taking on new roles and working under the stress of pandemic like conditions, training strategies will need to be evolved and built into teaching and training systems. Clinical engagement and ability and strategies to maintain some form of training during pandemic periods will ensure that junior doctors do not feel distanced from core learning and maintaining surgical skills.

References

- World Health Organization (2020). WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- NHS England (2015). Emergency Preparedness Resilience and Response Framework 2015. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/eprr-framework.pdf.

- NHS England and NHS Improvement (2020). Letter to chief executives of all NHS trusts and foundation trusts: IMPORTANT AND URGENT – NEXT STEPS ON NHS RESPONSE TO COVID-19 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/urgent-next-steps-on-nhs-response-to-covid-19-letter-simon-stevens.pdf.

- NHS England (2020). Redeploying your secondary care medical workforce safely. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/Redeploying-your-secondary-care-medical-workforce-safely_26-March.pdf.

- Seyedin H, Zaboli R, Ravaghi H. Major incident experience and preparedness in a developing country. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(3):313-8.

- Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD, Ren AK, Zhou XP. [Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2020;38(3):192-5.

- Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun. 2020. Mar 30. [Epub ahead of print].

- Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Jing M, Goh Y, Yeo LLL, et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020. Apr 26:M20-1083. [Epub ahead of print].

- Chatterjee SS, Barikar CM, Mukherjee A. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing mental health problems. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102071.

- Artino AR Jr, La Rochelle JS, Dezee KJ, Gehlbach H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Med Teach. 2014;36(6):463-74.

- Geldsetzer P. Use of Rapid Online Surveys to Assess People's Perceptions During Infectious Disease Outbreaks: A Cross-sectional Survey on COVID-19. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e18790.

- Phillips AW. Proper Applications for Surveys as a Study Methodology. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(1):8-11.

- Gonzi G, Gwyn R, Rooney K, Horner M, Roy K, Boktor J, et al. Our experience as Orthopaedic Registrars redeployed to the ITU emergency rota during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Transient Journal. May 2020. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/our-experience-as-orthopaedic-registrars-redeployed-to-the-itu-emergency-rota-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.html.

- Bakewell Z, Davies D, Allanby L, Dhonye Y. Pandemically challenged: developing a ward-based cross-skilling programme. Med Educ. 2020. [Epub ahead of print].

- Craft LL, Perna FM. The Benefits of Exercise for the Clinically Depressed. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(3): 104-11.

- Greist JH, Klein MH, Eischens RR, Faris J, Gurman AS, Morgan WP. Running as treatment for depression. Compr Psychiatry. 1979;20(1):41-54.

- Martin G, Khajuria A, Arora S, King D, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. The impact of mobile technology on teamwork and communication in hospitals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(4):339-55.