Rapid evolution of services during the COVID-19 pandemic: the challenges faced by an island district general hospital

By Tom Moore and Imad NajmTrauma & Orthopaedics, St Mary’s Hospital Isle of Wight

Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Published 03 July 2020

Editors Note: We thank the author of this and other previous descriptive articles relating to COVID-19. However, as outlined in the current editorial the focus is now to be on looking forward rather than back or even something other than the coronavirus. So this may be the last of its type.

Abstract

In common with all hospitals around the country, Isle of Wight NHS Trust has made significant changes to its operating model since the onset of the Coronavirus pandemic, and resultant ‘lockdown’ of society in March 2020. Many of these changes will be familiar to anyone working elsewhere in the health service, but as a district general hospital serving an island community we faced particular challenges around provision of critical care and transfer of patients to tertiary referral centres. In this article we explain the nature of these challenges and detail the steps taken to overcome them, in the hope that our experience may prove interesting and perhaps help to inform care elsewhere.

Introduction

It hardly needs to be said at this stage that the coronavirus has had a huge effect on healthcare systems and services around the world, not to mention the broader impact on society as a whole in terms of economic damage, curtailment of personal freedoms, excess deaths and countless other effects.

In what we must seemingly inevitably refer to as ‘these strange and unprecedented times’, many articles have been published detailing the changes to acute care services and the impact they have had, and doubtless many more will be written when the longer term impact on care – for example, delayed cancer surgery, curtailed screening programmes and reduced mental health provision, to name a few – becomes apparent.

At the Isle of Wight NHS Trust, we’ve made many of the changes at a hospital level documented elsewhere1, for instance, in orthopaedics we cancelled all elective operations, restructured fracture and elective clinics to allow phone and video-based consultations to minimise face-to-face interactions, and increased our presence in ED to facilitate rapid decision making and management of orthopaedic problems. Colleagues from other departments made similar changes to their services.

Our main theatres were requisitioned by intensive care to provide ventilated bed spaces if their capacity was exceeded, and so the hospital has run just one theatre in the day-case unit for all emergency procedures during the lockdown. This has meant careful negotiation with surgical colleagues has been required to prioritise the workload, and in orthopaedics has meant that in the first 10 weeks of the lockdown we have performed just 103 operations, compared with 472 over the same period in 2019 – a drop of 78%, (see Table 1).

|

|

23/03 – 31/05 2019 |

23/03 – 31/05 2020 |

Year on year change |

|

Elective |

339 |

0 |

-100% |

|

Trauma |

133 |

103 |

-22.6% |

|

Total operations |

472 |

103 |

-78.2% |

None of this will come as news to most readers, but as an island we also faced a unique set of circumstances going into this crisis. The Isle of Wight was identified in March by the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science as one of five ‘healthcare deserts’ in the country where medical services could quickly become overwhelmed in the event of a large-scale disease outbreak2. This finding was based on three factors – first, a very low number of critical care beds. With just six available in normal circumstances, the trust has just 4.3 per 100,000 of the resident population of the island, against a UK average of 8.9 (itself the joint-second lowest in Europe)3. Under normal circumstances the island population can double during the peak summer season, putting even further pressure on the ability of the healthcare service to care for critically ill patients.

The second issue is the age profile of our patients. From a total population of 140,984, 27.3% are over 65 compared with just 18.2% for England and Wales as a whole and 19.1% for the South East region4. Given that 80% coronavirus-related of deaths in the UK have occurred in those aged over 705, there was a presumption that our patient cohort would be severely affected by the disease.

Finally, we are physically separated from our local tertiary referral centres by the Solent. Ironically, at just 20 miles as the crow flies our trust is the closest district general hospital in the region to the local major trauma centre (Southampton General Hospital), and yet it is also the most remote, with emergency patient transfers probably taking longer to organise than from anywhere else. There was a concern within the Trust that if the other, larger hospitals in our Wessex network became overwhelmed during a spike in cases of coronavirus patients it may seriously impede our ability to get critically ill or injured patients off the island in a timely fashion.

Below we will detail how some of these challenges were addressed.

Key organisational challenges

Bed Capacity

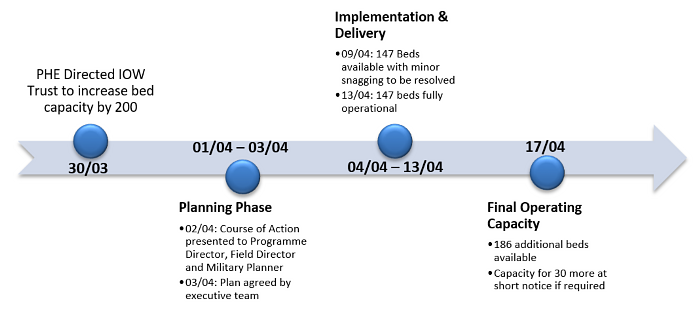

Based on the island’s demographics, modelling from the Department of Health suggested that the Trust would require 48 ventilated beds in the event of a significant disease outbreak, with an additional 200 beds to provide ‘step down’ care. This would be in addition to the Trust’s normal operating capacity of 220 beds (including six ventilated intensive care beds).

This modelling was released to the Trust board on the 30th of March, and within just 48 hours the project management team had identified three sites within the hospital’s existing footprint which could be used to effectively double its capacity. These included the Trust’s education centre, the ‘Laidlaw’ day hospital, and the outpatient records store. The onsite staff accommodation block was also identified as a possible site which could be used in extremis, but as this would require the displacement of large numbers of key staff the plans for this area was kept as a contingency only.

The scale of the logistical challenge cannot be overstated. Whilst the Laidlaw unit was at least already in clinical use, it required significant building work and internal structural changes to accommodate the required number of beds. The education centre required the removal of the Trust’s library collection and conversion of multiple office-based rooms, including a lecture theatre, into wards. The biggest challenge by far, however, was in converting the outpatient records store to clinical use. This had been used to house over 140,000 sets of notes, which had to be moved offsite to a new facility on a nearby industrial estate before building work could begin (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Over 140,000 medical records were removed from a storage building to an offsite unit to create capacity for up to 69 step-down beds over a period of two weeks.

To help with this herculean effort a detachment of 40 personnel from the Scots Guards was deployed to the island, and along with a team of local contractors they worked 12 hour shifts seven days a week. Astonishingly, the entire reconfiguration of the site was completed within two weeks (Figure 2) at an estimated cost of £500,000 (taken from a £48m capital grant allocated to the Trust for building and IT improvements last year)6. The project’s director estimated that under normal circumstances building work of this cost and scale could spend 12 months in the planning stages alone before being signed off for implementation.

Figure 2: Implementation timeline of IOW Trust reconfiguration to provide >200 additional beds.

Like the Nightingale hospitals rapidly put up around the country, the predicted surge in infections on the island did not materialise, and this extra capacity has so far not had to be used. The Trust is keen to ensure that the new facilities do not become expensive white elephants however. Whilst the old medical records building is being held empty in case it is needed now the lockdown has been eased (or if virus cases spike over the winter), the other two areas are being used for cancer pre-assessment and community step down care, shielding vulnerable patients from having to enter the main hospital building. These units will be ready to rapidly convert back to their ward configurations at short notice if required.

Transfers

The Isle of Wight NHS Trust works in partnership with Queen Alexandra Hospital to treat patients with a number of medical conditions which cannot be managed on the island, as well as transferring critically injured patients to Southampton General Hospital via the Wessex Major Trauma Network. Neither of these partner hospitals are more than 20 miles away, however our physical separation from the mainland presents unique challenges in transferring patients.

Traditionally, urgent but non-emergency cases, such as patients requiring coronary care, have been transferred by ambulance and vehicle ferry using a scheduled service on a commercial operator. Vehicle slots on the ferry have to be booked in advance (and can fill up with retail customers quickly, especially in the summer), and the difficulty in co-ordinating these slots with ambulance availability means that there is on average an agonisingly slow 7-10 day wait between making the decision to transfer a patient and it actually happening.

Emergency transfers are quicker, but also face logistical challenges. For example, whilst major trauma should bypass our site entirely and be taken straight to the local MTC, Southampton, a higher proportion comes in via our Emergency Department than at other DGHs as the air ambulance is not always available to pick up injured patients at the scene of the incident. For these patients (as well as trauma ‘upgraded’ in severity once it has reached the hospital), onward transfer must be arranged. Ideally this would be via the air ambulance, however this service covers the whole of Wessex and is not always available in a timely fashion; moreover it cannot fly between 02:00 and 07:00 in the mornings due to Civil Aviation Authority rules. The Coast Guard also operate a helicopter service which is able to take injured patients, however they have a 45 minute ‘stand to’ time after they are called, do not have the ability to take a critical care team with the patient, and again have to provide cover for the entire South Coast of England and so are not always readily available.

In the event that air transport is not available, the patients have to be transported by ferry. A priority vehicle slot is made available for emergency ambulance transfers, however even with this the average door-to-door time from St Mary’s Hospital on the Isle of Wight to Southampton hospital is over three hours. Moreover, nursing and anaesthetic staff have to accompany the patient through their whole journey and there is no prioritisation system to return them to the island, meaning that for each emergency transfer two or three key staff members can be effectively lost from our hospital for 7-8 hours.

Clearly there was room for improvement in this system, and our transfer and logistics team saw an opportunity in the organisational chaos wrought by COVID-19 to innovate. Released from the usual bureaucratic impediments to rapid change, they approached commercial operators of a hovercraft on the island to see if they might provide viable alternatives to the ferry service.

The operators agreed to help, and a feasibility trial was carried out in which a hovercraft was fitted with all the necessary equipment to transfer a bed-bound patient safely and a mannequin with a simulated head injury was intubated, ventilated and transferred off the island. During the 15 minute sailing time across the Solent the transfer team successfully simulated a cardiac arrest and defibrillation, as well as a ventilator equipment failure and full circuit change. Upon arrival at Southampton port the ‘casualty’ was received by a waiting team from the South Central Ambulance Service (SCAS) and taken to Southampton General Hospital, resulting in a total door-to-door transfer time from St Mary’s of 45 minutes. A similar time was achieved for a simulated transfer to Queen Alexandra hospital in Portsmouth.

Having proven the concept, the vessel operators have been contracted on a ‘pay-as-you-go’ basis to provide round the clock back up urgent transfers when air transport is not available. Because of their quick travel times (15 minutes compared to over an hour for the vehicle ferry to Southampton) they are able to offer the Trust a priority service and can delay their scheduled retail passenger operations for a few minutes if necessary. The involvement of SCAS means that our trust no longer needs to send highly qualified staff with the patients for the entirety of their journey, and as the turnaround times are quicker as well it means that critical care nurses and anaesthetists now only need to be away from the hospital for two hours at most, compared to the loss of a whole day previously.

As of the 31st May the hovercraft service has been used to transfer 26 patients, mostly from coronary care, with plans to expand its use to unwell maternity patients in the next few weeks. As yet it has not had to be used for major trauma, but it is reassuring to know that the capacity is there if required.

Ultimately, the trust is aiming to define a new gold standard for inter-hospital transfers of critically injured or ill patients, and this system will play a part. A full audit of its performance compared to the pre-existing arrangements is ongoing, and will hopefully be published in due course.

Conclusion

We have seen in these examples that, when required, even famously intransigent NHS organisations are capable of rapid change given the right resources and willpower. Where there is a well-defined problem and an identifiable solution, Trusts, departments and individuals should be given the freedom to implement them. Employing the ‘agile’ methodology so beloved of management consultants, ideas should be worked up, tested and allowed to flourish or ‘fail fast’.

Of course not all innovations are guaranteed success – a case in point is the much-vaunted COVID-19 tracing app launched to great fanfare on the island at the beginning of May. Although the Trust had no involvement in its creation, it enthusiastically supported its roll-out amongst staff members and the wider community by sending out daily email exhortations to download and use it, and placing prominent printed advertisements throughout the hospital. This was despite the fact it had failed the NHS’ own critical privacy and safety tests7 prior to launch, and after a two month period in which it was discovered that it didn’t even work properly on certain phones it was eventually unceremoniously scrapped after wasting £11.8million8.

However, this should not detract from the message that, post-COVID-19, the NHS is likely to need more innovation rather than less, and we have shown here that even on a small scale real achievements can be made quickly.

References

- De C, Paringe V, Agarwal S, Brooks M, Harbham P. COVID-19 Pandemic response of Trauma and Orthopaedic services – The journey of a NHS District General Hospital in West Midlands. The Transient Journal. June 2020. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-pandemic-response-of-trauma-and-orthopaedic-services-the-journey-of-a-nhs-district-general-hospital-in-west-midlands.html.

- Verhagen MD, Brazel DM, Dowd JB, Kashnitsky I, Mills M. Forecasting spatial, socioeconomic and demographic variation in COVID-19 health care demand in England and Wales. OSF Preprints, 21 Mar. Available at: https://osf.io/g8s96/.

- The King's Fund (2020). NHS hospital bed numbers: past, present, future. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs-hospital-bed-numbers.

- Public Health England (2018). Isle of Wight: Local Authority Health Profile 2018. Available at: https://www.iow.gov.uk/azservices/documents/2552-Health-Profile-Isle-of-Wight-2018.pdf.

- Office for National Statistics (2020). Deaths registered weekly in England and Wales. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/weeklyprovisionalfiguresondeathsregisteredinenglandandwales.

- NHS Isle of Wight Trust (2019). NHS leaders on the Isle of Wight welcome £48 million funding boost. Available at: https://www.iow.nhs.uk/news/NHS-leaders-on-the-Isle-of-Wight-welcome-48-million-funding-boost.htm.

- Rapson J. ‘Wobbly’ tracing app ‘failed’ clinical safety and cyber security tests. (HSJ 4th May 2020). Available at: https://www.hsj.co.uk/technology-and-innovation/exclusive-wobbly-tracing-app-failed-clinical-safety-and-cyber-security-tests/7027564.article.

-

Crouch H. Tory peer reveals NHS contact-tracing app has cost £11.8m to date. (Digital Health 23 June 2020). Available at: https://www.digitalhealth.net/2020/06/nhs-contact-tracing-app-cost/.