The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on orthopaedic practice: perspectives from Asia-Pacific

by Andrew Chia Chen Choua,b, Ryuichiro Akagic, Joe Chih-Hao Chiud, Hyuk-Soo Hane, Denny Tijauw Tjoen Liea,b

aDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, Division of Musculoskeletal Sciences, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore.

bDuke-National University of Singapore Medical School, Singapore.

cDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, Chiba University Hospital, Chiba, Japan.

dDepartment of Orthopaedic Sports Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan.

eDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Corresponding email: [email protected]

Published 30 April 2020

Introduction

The very first case of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in Wuhan, China on 31st December 2019 to minimal, if any, response from the orthopaedic community1. However, weeks before human-to-human transmission was confirmed by the World Health Organization (WHO), the virus had spread throughout Asia: Japan reported its first case on the 16th of January 2020, followed by South Korea on the 20th, Taiwan on the 21st, and Singapore on the 23rd2-4. By March 12th 2020, over 125,000 patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 globally and the WHO officially declared it a pandemic1.

While COVID-19 does not have any obvious orthopaedic manifestations, the pandemic has had profound impact on orthopaedic practices globally in view of the sudden and significant demand on healthcare systems around the world. Particularly for the orthopaedic departments who have weathered the severe acute respiratory disease (SARS) outbreak 2002, surgeons in Asia knew what to expect and were prepared to weather months of disruption to their practice. Here, we share the experiences and strategies orthopaedic departments from across Asia-Pacific have adopted in response to the COVID-19 outbreak.

In general, goals of orthopaedic practice during the pandemic were as follows:

- Protect both patients and healthcare staff from COVID-19 infection.

- Ensure delivery of essential orthopaedic services.

- Provide continuity of care for existing patients.

- Optimize and conserve clinical manpower and resources.

- Maintain clinical education and training standards.

Protection of patients and healthcare workers

The first and foremost priority was safety for both patients and healthcare staff. To minimize risk of transmission of COVID-19 from patient to patient, patient to staff, and staff to staff, a multitude of practice alterations were necessary after discussion with colleagues from nursing, infectious diseases, and anaesthesiology. The definition of a suspected COVID-19 case varied depending on each individual country’s guidelines, but criteria usually consisted of fever of T > 38.5oC, upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) symptoms, travel in the last 14 days to an endemic region, and contact with a confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patient.

Healthcare workers

Strict guidelines for personal protective equipment (PPE) required for patient contact were developed after consulting infectious disease specialists and usually dictated the need for an N-95 mask, goggles or disposable visor, disposable gown, and disposable gloves for contact with any patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, as shown in Figure 1. All staff were taught how to properly don and doff their gear, as well as the proper hand hygiene required beforehand and afterwards. Staff members were also advised to attend a mask fitting session to ensure correct sizing for N-95 masks. In the event of poor fit, staff were fitted with and taught how to use a powered air-purifying respirator for contact with high-risk patients or during aerosolizing procedures (e.g. intubation). If unsure of contact precautions, orthopaedic staff were advised to consult their infectious disease colleagues or to treat patients as per a suspect COVID-19 case.

Figure 1. Healthcare staff donned in full personal protective gear escorting a suspected COVID-19 patient in Singapore11.

To minimize risk of disease transmission between healthcare workers, orthopaedic departments often split into an emergency/inpatient team, an outpatient clinic team, and an operating team that functioned as independent units. Usually, these teams consisted of a mix of junior and senior staff, as well as a mix of subspecialties (e.g. trauma, spine, tumor, foot and ankle), and were rotated every 1-2 weeks. Senior attendings or consultants were designated as in-charge of their teams and teams were deliberately kept segregated from one another, usually communicating by email or instant messaging platforms such as WhatsApp or TigerConnect. This was to ensure that, in the event a surgeon or resident physician contracted COVID-19, their team could be quarantined and another team could step in and cover their duties seamlessly with minimal disruption to service and risk of cross-contamination.

All healthcare staff, including surgeons, resident physicians, nurses, and allied health staff, were issued thermometers and required to log their temperature twice daily. If they developed a fever or symptoms suggestive of an URTI, they were advised to seek medical attention and to inform their supervisor. Healthcare workers were further advised to receive their annual influenza vaccination.

Inpatient wards

All patients prior to any admission were required to undergo temperature screening and triaged for URTI symptoms, travel history, and contact history. Patients with suspected COVID-19 were advised for cancel elective admissions and referred to the emergency department for further assessment or, if admitted for emergency orthopaedic conditions, referred to the infectious diseases team as an inpatient. If admitted, these patients were isolated into single rooms until de-isolated by infectious disease specialists.

In addition to wards set aside for COVID-19 patients, a separate ward was set aside for surgical and orthopaedic patients with suspected COVID-19 and/or contact with confirmed cases, as well as for patients with musculoskeletal infections. When possible, arthroplasty patients or patients with hardware were kept separate from the aforementioned patients to minimize risk of infection and discharged to home or step-down care as soon as possible. Manpower permitting, separate inpatient teams managed the orthopaedic patients with suspected COVID-19 exposure and the remaining orthopaedic patients to allow for physical segregation of both patients and healthcare staff. All inpatients were issued surgical masks and advised to wear them at all times, even when in bed. Hand hygiene was reinforced daily by nursing. Inpatients were further restricted to one visitor at any given time and all visitors were subject to the same temperature screening and triaging as described above. Additionally, they were required to leave contact details in the event contact tracing was required.

Operating theaters

For patients admitted electively or as a same day admission for urgent procedures (e.g. fracture fixation), patients were assessed as above for potential COVID-19 infection. If suspected, patients were strongly encouraged to postpone their surgeries and seek medical attention at an emergency department or a designated disease center.

For patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 requiring surgery, specific workflows were required and drafted in conjunction with specialists from anaesthesiology and infectious diseases. All healthcare staff, including surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and other allied health professionals, were required to don full PPE when handling suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases. To minimize risk of transmission, the number of staff required to perform the case and the operating time was kept to a minimum. As intubation is considered an aerosolizing procedure, regional or local anesthesia was strongly recommended and surgeons and other staff not required for intubation were required to leave the room during intubation. In Singapore, many hospitals designated a separate isolation operating theater with its own surgical reception and post-anaesthetic care unit to avoid cross-contamination with other patients. In Taiwan, a separate negative pressure isolation theater was prepared for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. If the theater was not available, such cases were arranged to be done last on the schedule.

Outpatient clinics

In addition to strict temperature screening for all visitors, patients and family members attending outpatient visits were triaged as above for COVID-19 infection. All visitors were required to wear masks before being allowed into the hospital. Both Taiwan and Singapore enforced social distancing norms in the clinic, with patients required to maintain at least one empty seat or 1-meter distance from one another, as shown in Figure 2. Hand sanitizer was made available freely throughout clinics and hand hygiene was strongly encouraged.

Figure 2. Enforcing social distancing in the clinics and hospitals in Taiwan. The signs on the chairs read “do not sit here” in Mandarin Chinese.

Conversion to essential services

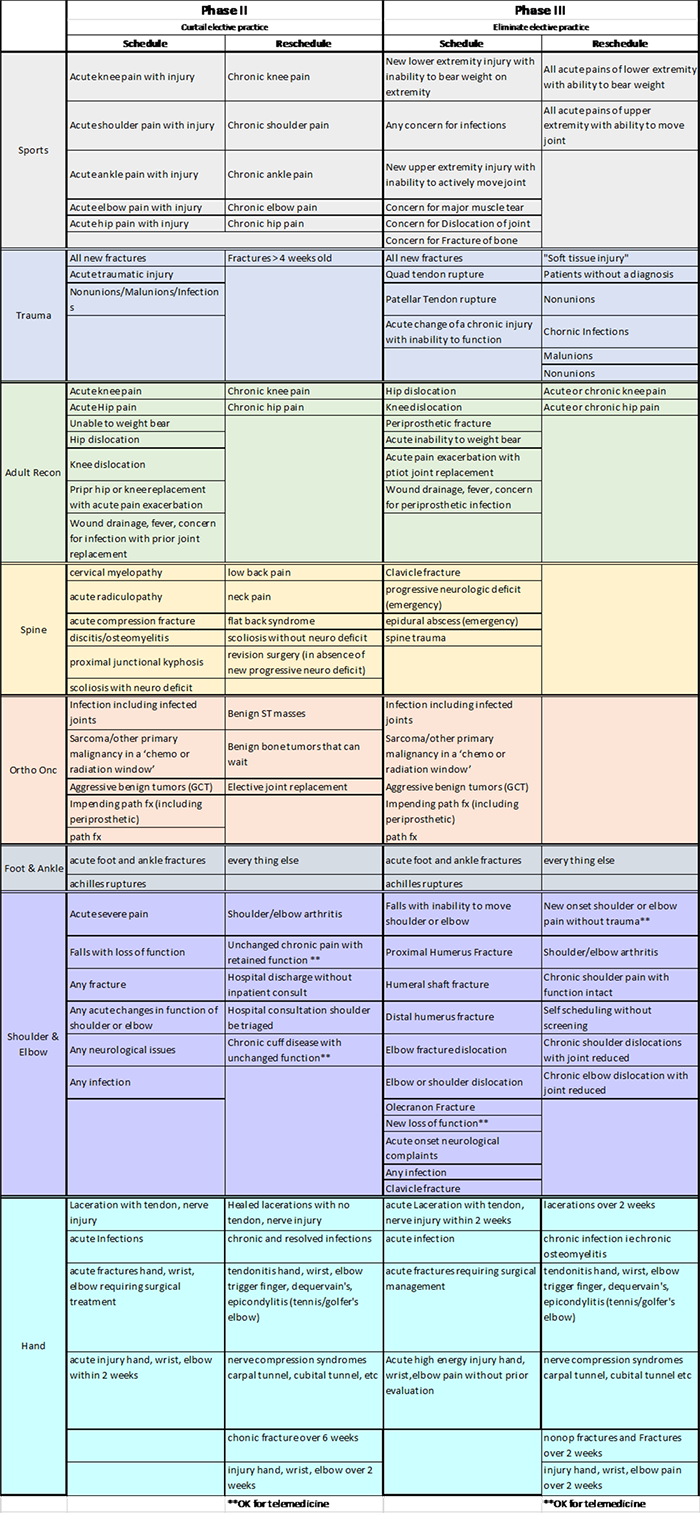

In the face of COVID-19, a highly infectious, potentially fatal virus, the decision was made virtually across the board by our departments of orthopaedic surgery to focus only on delivering essential services in order to minimize risk of exposure to both patients and surgeons. Typically, this meant that only cases deemed clinically unstable or requiring timely intervention were allowed to proceed, which often only included trauma, infection, tumor, or spine cases with worsening neurology. All other cases were deemed elective and either postponed or cancelled entirely. The Japanese Orthopaedic Association advised using the American College of Surgeons and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidelines for triaging orthopaedic patients to determine which cases could be safely postponed and which should proceed with surgery, as shown in Table 15,6. Patients who required admission for surgery were advised to minimize their length of stay or opt for day surgery if possible.

Table 1. COVID-19 Guidelines for Triage of Orthopaedic Patients, as recommended by the American College of Surgeons and University of Pennsylvania6.

Logistically, immediately cancelling or postponing cases was not possible and disrupted continuity of care, thus for many departments, a gradual tapering down of elective surgeries was conducted. Even before the Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level was raised to orange in Singapore on February 7th 2020, multiple surgical departments in Singapore had already begun to reduce elective surgeries7. By the time the Singaporean health minister stated that only essential services would continue operating on April 4th 2020, most patients had already been rescheduled or counselled accordingly about postponing elective surgeries8.

In the outpatient setting, patients with conservatively managed, non-operative, and non-urgent conditions were given an increased longer duration of follow-up appointments. For medication refills, both Singapore and South Korea encouraged remote prescription refills, with Taiwanese hospitals even providing a fast-track medication service outside the hospital setting to minimize patient traffic to the hospital. Surgeons were also advised to consider non-surgical management of symptoms to delay the need for surgery, such as intra-articular injections and extracorporeal shockwave therapy. Conducting outpatient visits via telemedicine was also explored in Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, while Japanese hospitals have uploaded home exercise videos online in order to allow patients to avoid coming to the hospital for their physiotherapy. An example of a telemedicine consult service from South Korea is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Telemedicine consults via videoconferencing in South Korea.

Conservation of clinical resources

While orthopaedic surgeons are not frequently part of the care team managing patients with COVID-19, as part of the greater healthcare community, the choices orthopaedic surgery departments make have both direct and indirect impact on critical resources during such a pandemic. By converting to essential services as described above and eliminating or restricting elective surgeries, additional hospital beds, including ICU and high dependency beds, equipment, and consumables can be made available for caring for COVID-19 patients. In Japan, hospitals placed caps on elective surgeries and limited occupancy by 20% in order to ensure a surplus of beds for COVID-19 patients. Similarly, reductions in admissions and elective surgeries in Taiwan allowed for conversion of double or triple bedded rooms into single rooms for use as isolation rooms. In South Korea, where a peak of 909 new cases were reported in a single day on 29 February 2020, hospitals closed down entire wards at a time in order to set up disaster ICUs and dedicated COVID-19 wards in order to handle the increased clinical load9.

With reduced surgeries, admissions, and outpatients clinics, the focus of the orthopaedic surgeons and resident physicians has shifted to alleviating the burden on our medical colleagues. In Singapore, orthopaedic residents, as well as residents from other surgical specialties, who have received critical care training or rotated through emergency medicine have been redeployed to ICUs and emergency departments to alleviate the manpower crunch10. Likewise, hospitals in Japan called for volunteers from all specialties early on to help reduce the clinical burden on their medical colleagues. With reduced surgeries to covers, our colleagues in anaesthesiology were also freed up to bolster critical care units with their skills and knowledge. Allied health staff, in particular nursing staff, from the operating theaters and outpatient clinics have also been redeployed to the inpatient wards, emergency departments, and critical care units. In addition to the obvious benefits in addressing the increased clinical load in the emergency and critical care setting, redeploying manpower also helps to reduce burnout and build camaraderie between colleagues during times of crisis, regardless of background and subspecialty.

Disruption of education and training

With the disruption to clinical services and enforcement of social distancing, medical education and residency training were inevitably disrupted. Across the board, medical students were withdrawn from clinical rotations in the hospital to avoid exposing students to COVID-19. As much as possible, undergraduate medical education was made online, through didactic lectures, discussion groups via teleconferencing using Zoom or WebEx, and instructional videos. Currently, only Taiwanese medical students have been reintroduced to the hospital setting, with strict emphasis on PPE usage and social distancing. Japanese medical schools have gone as far as postponing the start of their school terms. Although bringing medical education online has not affected the progression and graduation of medical students thus far, we do acknowledge that it is not a substitute for hands-on clinical education and would not advise for its routine use outside of extenuating circumstances.

Similarly, resident physicians have been profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. To prevent inter-hospital transmission of COVID-19, residents have been restricted from rotating out of the institutions they were posted to at the start of the outbreak. Particularly as surgical training requires rotating through a wide variety of subspecialties and settings that may not be available in the same institution, this means that graduating residents may not be able to complete required postings (e.g. paediatric orthopaedics or hand surgery). Centralized residency teaching and national orthopaedic conferences have either been outright cancelled or converted to virtual form if possible. Training workshops and courses have switched to teleconferencing and if unable to (e.g. cadaveric courses), have been outright cancelled. While Taiwan has managed to keep national board exams for residents on schedule, in other countries, national board and exit exams have been postponed, sometimes indefinitely.

With the COVID-19 outbreak spreading internationally, visiting fellowship programs have been cancelled across the board. Furthemore, medical staff in Taiwan and Singapore have been further restricted from overseas travel for conferences, courses, or fellowship training until at least after June. In some cases, fellows were recalled from their overseas fellowships just months after they had started.

Conclusion

Despite the proximity of Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan to the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, proactive responses and meticulous planning from our respective institutions have mitigated the effects of the pandemic on delivery of orthopaedic care. While elective surgeries have been postponed and clinic volume has been reduced, no surgeons or residents from the aforementioned countries have been reported as contracting the COVID-19 virus, no patients admitted to the orthopaedic services have developed nosocomial COVID-19 infections, and essential orthopaedic surgery services continue to be delivered within our respective countries.

Although orthopaedic surgeons are not commonly involved in the management of pandemics, we hope the lessons we have learned and experiences we have had may be beneficial to our colleagues internationally in managing their own orthopaedic units during times of crisis.

References

- World Health Organization (2020). Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

- Kim I, Lee J, Lee J, Shin E, Chu C, Lee SK. KCDC Risk Assessments on the Initial Phase of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11(2):67-73.

- Wong JE, Leo YS, Tan CC. COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA. 2020 Feb 20. [Epub ahead of print].

- Cheng S-C, Chang Y-C, Chiang Y-LF, Chien Y-C, Cheng M, Yang C-H, et al. First case of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(3):747-51.

- Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2020). Non-Emergent, Elective Medical Services, and Treatment Recommendation. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf.

- American College of Surgeons (2020). COVID-19 Guidelines for Triage of Orthopaedic Patients. Available at: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case/orthopaedics.

- Chew M-H, Ong LW, Koh FH, Ng A, Tan Y, Ong B-C. Guest post: Lessons in preparedness–the response to the COVID-19 pandemic by a surgical department in Singapore. Available at: https://cuttingedgeblog.com/2020/03/29/guest-post-lessons-in-preparedness-the-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-by-a-surgical-department-in-singapore/.

- Channel News Asia (2020). COVID-19: Essential healthcare services to continue operating, other services to be scaled down. Available at: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/healthcare-services-clinics-closed-covid-19-coronavirus-12609404.

- Normile D. Coronavirus cases have dropped sharply in South Korea. What’s the secret to its success. Science. 2020;17(03).

- Liang ZC, Ooi SBS. COVID‐19: A Singapore Orthopedic resident’s musings in the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(4):349-50.

- The Straits Times: Tan A. New Singapore study shows early immune system response in Covid-19 patients could cause respiratory distress. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/new-singapore-study-shows-early-immune-system-response-in-covid-19-patients-could.