How can we sustain the workforce and standards of care currently provided within the NHS?

By Simrat Tiwana

Final year medical student at the University of Leicester

|

This essay was a runner-up in the 2023 BOA Medical Student Essay Prize With the changing demographics and working practices within T&O, how can we sustain the workforce and standards of care currently provided within the NHS? |

Introduction

An ageing population with increasing comorbidities and needs, have placed huge pressures on surgical specialities. Data released in February 2022 by NHS England, reported that waiting lists for elective trauma and orthopaedic (T&O) surgeries were among the highest in the country. This was a 21% increase on the previous year1. In March 2022, there were over 730,000 people on the T&O waiting lists in England2.

Although increasing pressures on services have been a long recognised issue. The cancellation of elective procedures and redeployments of staff during the COVID-19 pandemic has served as a significant aggravator. This has had a detrimental effect on mental health, leaving doctors demoralised and burnt out3.

Increasing numbers of doctors are considering plans to leave or take a break from working in the NHS4. From 2016 to 2021, 481 trainees left surgical training5. The British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) has accredited staff shortages and morale issues as partially responsible for the challenges faced by the specialty2.

Retention of the workforce has been identified by the NHS and surgical organisations as a key issue to focus on in coming years.

As we recover from the physical impacts of this global phenomenon. We must also in turn consider the psychological impacts on doctors and the consequential repercussions for patient safety and care.

Recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on surgical practices6. During the pandemic there were over 250,000 fewer elective orthopaedic operations7. With elective procedures being a significant contribution for teaching opportunities, this has been a significant hindrance to competency achievement and trainee progression. During the height of the pandemic, trainees were also redeployed to other specialities. The delay in progression through training threatens the ability to meet future demand for consultant surgeons.

It is imperative that training be made a priority in the plans to tackle the elective backlog8. This may be achieved with the use of simulation training and augmented reality systems to aid trainees in acquiring technical skills. Virtual reality training has already shown to be effective in improving arthroscopy skills with repeated use9. There may be potential benefit from formally integrating simulation training into the orthopaedic training curriculum10.

Meaningful feedback

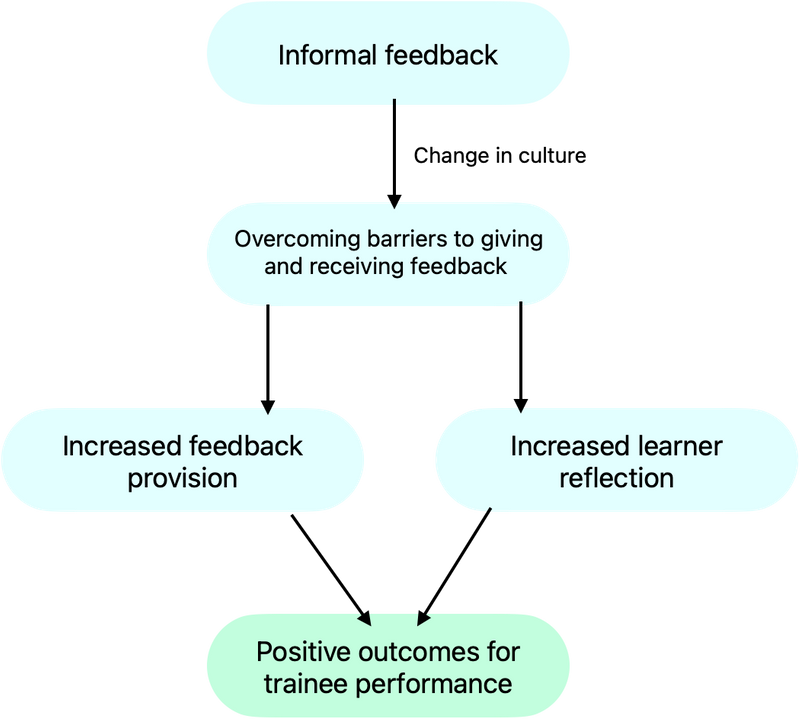

Focused and specific feedback has been noted to influence trainee performance. Frequent reflection encourages positive attitudes to receiving feedback and breaks down the anxieties and negative perceptions surrounding the feedback process11. Encouraging a culture where feedback is encouraged in conversation, not only in formal supervision meetings, enables the development of self-reflection techniques.

Frequent reflection among colleagues will also open up discussions on the emotional tolls and job stresses that ultimately impact performance and indeed patient care.

Alternative training pathways

Traditionally seen as a male dominated field there has been a positive change in the diversification of surgical trainees. Between 2011 and 2020 the total proportion of female registrars across all surgical specialities has risen from 25.3% to 34.2%12. However, this is not reflective of the proportion of female medical students. This may be in part due to assumptions that a career in surgery is incompatible with raising children and maintaining family life13. If we wish to encourage more female trainees, there is a need to increase accessibility to flexible training.

Promoting education on potential training routes early on in the training process will ensure that support can be more readily accessed14. Assimilating the idea of alternative training pathways as a new norm will work to break down the stigma and negative connotations surrounding these routes13.

Fellowships

T&O is becoming increasingly specialised and growing numbers of trainees intend to complete subspecialty fellowships15. This has been influenced by a growing emphasis for trainees to have subspecialty fellowship experience prior to consultancy16. At present there is no national information source for fellowships available in the UK. Trainees can be expected to make decisions without a comprehensive knowledge of what to expect from a post. With a growing trend of trainees intending to undertake fellowships, a national source of information that details clear objectives of fellowships would be an indispensable aid for surgical trainees.

Wellbeing

Increasing clinical demands aggravated by the added pressures of the pandemic have meant there are unprecedented pressures on surgeons. In a 2021 survey conducted by the BOA, 40% of the 1,298 respondents reported burnout17. Burnout is characterised by feelings of exhaustion, low energy and negative feelings surrounding work18,19. It has been linked to poor clinical performance and threatens patient safety. Those experiencing it are more likely to express a desire to leave the profession.

Despite national campaigns targeting mental health20, the stigma surrounding the subject means there is still reluctance to disclose such problems. Challenging this requires high quality support provided at a hospital and team level. Utilising peer support is key to enacting a successful change in culture. Providing education and evidence of the repercussions of physician health on patient care21 will provide the groundwork to encourage a change in attitudes and begin to facilitate discussions between colleagues.

Surgeons are more likely to feel comfortable discussing their challenges with colleagues who can empathise with their situation rather than a mental health professional3. Encouraging these conversations can be a powerful way to challenge mental health stigma within T&O22.

Conclusion

The priorities of T&O should focus on supporting trainees. There needs to be a national commitment in prioritising the acquisition of competencies and continued progression through surgical training.

There is an ever increasing need to represent the changing needs of surgeons. Establishing a culture that recognises and acknowledges the needs of its staff will lead to improved levels of job satisfaction and workforce retention23. Patient satisfaction has been shown to be markedly higher in organisations where staff health and wellbeing are better21.

References

- British Orthopaedic Association. T&O waiting list the largest for over a decade. Available at www.boa.ac.uk/resources/t-o-waiting-list-the-largest-for-over-a-decade.html.

- British Orthopaedic Association. England and Wales T&O Waiting Times data for March 2022. Available at www.boa.ac.uk/resources/england-and-wales-t-o-waiting-times-data-for-march-2022.html.

- Royal College of Surgeons of England. Supporting the wellbeing of surgeons and surgical teams during COVID-19 and beyond. Available at www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/recovery-of-surgical-services/tool-6.

- British Medical Association. Catastrophic crisis facing NHS as nearly half of hospital consultants plan to leave in next year, warns BMA. Available at www.bma.org.uk/bma-media-centre/catastrophic-crisis-facing-nhs-as-nearly-half-of-hospital-consultants-plan-to-leave-in-next-year-warns-bma.

- Khalil, K., Sooriyamoorthy, T. and Ellis, R. (2022). Retention of surgical trainees in England. The Surgeon.

- Al-Jabir, A., Kerwan, A., Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Khan, M., Sohrabi, C., O’Neill, N., Iosifidis, C., Griffin, M., Mathew, G. and Agha, R. (2020). Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice - Part 1. International Journal of Surgery, 79, pp.233-248.

- British Orthopaedic Association. Trainee associations provide an urgent call to action to protect the future surgical workforce. Available at www.boa.ac.uk/resources/trainee-associations-provide-an-urgent-call-to-action-to-protect-the-future-surgical-workforce.html.

- Royal College of Surgeons of England. (2020). Recovery of surgical services during and after COVID-19. Available at www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/recovery-of-surgical-services/#s5.

- Aïm, F., Lonjon, G., Hannouche, D. and Nizard, R. (2016). Effectiveness of Virtual Reality Training in Orthopaedic Surgery. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 32(1), pp.224–232.

- Hasan, L.K., Haratian, A., Kim, M., Bolia, I.K., Weber, A.E. and Petrigliano, F.A. (2021). Virtual Reality in Orthopedic Surgery Training. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 12, pp.1295–1301.

- Fainstad, T., McClintock, A.A., Van der Ridder, M.J., Johnston, S.S. and Patton, K.K. (2018). Feedback Can Be Less Stressful: Medical Trainee Perceptions of Using the Prepare to ADAPT (Ask-Discuss-Ask-Plan Together) Framework. Cureus, 10(12).

- Newman, T.H., Parry, M.G., Zakeri, R., Pegna, V., Nagle, A., Bhatti, F., Vig, S. and Green, J.S.A. (2022). Gender diversity in UK surgical specialties: a national observational study. BMJ Open, 12.

- Harries, R.L., McGoldrick, C., Mohan, H., Fitzgerald, J.E.F. and Gokani, V.J. (2015). Less Than Full-time Training in surgical specialities: Consensus recommendations for flexible training by the Association of Surgeons in Training. International Journal of Surgery, 23.

- Motter, D. and Salimi, F. (2022). All roads can lead to surgery. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 73, p.103147.

- Ruddell, J.H., Eltorai, A.E.M., DePasse, J.M., Kuris, E.O., Gil, J.A., Cho, D.K., Paxton, E.S., Green, A. and Daniels, A.H. (2018). Trends in the Orthopaedic Surgery Subspecialty Fellowship Match: Assessment of 2010 to 2017 Applicant and Program Data. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 100(21), p139.

- British Orthopaedic Association. It’s time to think about… Fellowships. Available at www.boa.ac.uk/resources/it-s-time-to-think-about-fellowships.html.

- Caesar, B.C., Nutt, J., Jukes, C.P., Ahmed, M., Counihan, C.M., Butler-Manuel, W.R. and Khan, M. (2021). Burnout in trauma and orthopaedic surgeons: can the UK military stress management model help? Orthopaedics and Trauma, 35(5), pp.305–308.

- World Health Organization. Burn-out an "occupational phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases. Available at www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases.

- World Journal of Surgery. Burnout Among Surgeons in the UK During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cohort Study. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8547303/.

- NHS England. NHS Practitioner Health. Available at www.england.nhs.uk/gp/the-best-place-to-work/retaining-the-current-medical-workforce/health-service.

- Dawson, J. (2018). Links between NHS staff experience and patient satisfaction: Analysis of surveys from 2014 and 2015.

- People Management. How to start mental health conversations with your employees. Available at www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1743930/start-mental-health-conversations-with-employees.

- General Medical Council. Caring for doctors, Caring for patients. Available at www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/caring-for-doctors-caring-for-patients_pdf-80706341.pdf.