BOA Burnout and Wellbeing Survey Infographic and Results: time for a culture change?

Authors: Ben Caesar, Christopher Jukes, James Nutt, Callum Counihan, William Butler-Manuel and Maryam Ahmed

This article was published in Journal of Trauma & Orthopaedics, Volume 9 Issue 2, June 2021.

In early 2021, the BOA Burnout and Wellbeing Survey was launched. It was run through the BOA by a team based at the Trauma and Orthopaedic Department in Brighton, who have processed and analysed the 1,298 responses, approximately 25% of the BOA membership.

The problem?

Burnout has been defined as ‘a state of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion that results from long-term involvement in work situations that are emotionally demanding1.

Since Freudenberger defined burnout in 1974, the appreciation and awareness of burnout in doctors has been well established2-4. However, with the arrival of COVID-19 and the added stresses at work and home, burnout and wellbeing have been increasingly discussed. In this journal in December 2020, the issue of the pandemic of burnout was raised5. High levels of burnout have been shown to increase medical errors6-8, reduce job satisfaction9-11 and push doctors in to early retirement12-14. Burnout also impacts doctors’ general wellbeing withhigher rates of depression15,16 alcoholism17 and suicidal ideation18,19.

Addressing health and wellbeing in Trauma and Orthopaedics as a specialty is going to be essential in the upcoming return to routine elective surgery as the estimate of 1.4 million hip and knee replacements on waiting lists within the NHS was based on estimations to November 202020. The upcoming drive to alleviate the elective orthopaedic backlog will potentially take a heavy toll on a specialty which is already battling with high levels of burnout.

The mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers as a result of the current coronavirus pandemic highlighted in the British Medical Journal21 made the clear distinction that many will face issues of moral injury. Moral injury is a term that describes the distress experienced when circumstances clash with one’s moral or ethical code; although not a mental health illness, it may lead to the development of negative thoughts that in turn can contribute to the development of mental difficulties such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidal ideation. It also matches to one of Maslach’s six drivers of burnout, values mismatch22. Pair a highpressure job with a population that is unlikely to seek support or treatment in times of difficulty, such as surgeons, then the conditions are ripe for burnout to ensue23.

Burnout has consequences such as reduced emotional and physical wellbeing, absenteeism, and personnel turnover. Naturally this can have substantial costs not just for individuals, but for organisations both short and long term. It is worth noting therefore that burnout can be ‘contagious’ and has the ability to spread throughout individual units and organisations. A single individual who may be experiencing stress and feel out of control of their situation can quickly create a net negative attitude change to a department or team. This is a well-studied but poorly quantified phenomenon and can include the protagonist forming well-founded or strong arguments upon which to hang their frustration. Empathetic colleagues can fairly easily become swept up with the negative feelings24.

If burnout is not addressed and the wellbeing of staff brought to the forefront of everyone’s agenda in healthcare, then we risk not only the problems highlighted above but also a huge financial cost to our institutions. A study from the US estimated on a national scale, the conservative base-case model estimate was that approximately $4.6 billion in costs related to physician turnover and reduced clinical hours were attributable to burnout each year in the United States. This estimate ranged from $2.6 billion to $6.3 billion in multivariate probabilistic sensitivity analyses. At an organisational level, the annual economic cost associated with burnout related to turnover and reduced clinical hours was approximately $7,600 per employed physician each year25. This can be extrapolated roughly to a cost of $900 million or £665 million in the UK per annum based on approximately 120,000 NHS doctors and the current exchange rate in April 2021.

Methodology

The research group, based in Brighton, produced a survey utilising the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory26, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) questions for measuring ethnic group and national identity27 sex, gender identity and sexual orientation28 for quantitative data analysis.

For the qualitative data, a number of free text questions were included to ask about the cause of stress at work and at home, and there was a further section for any additional information or comments.

Statistical analysis was performed where appropriate utilising t-test or chi-squared calculations.

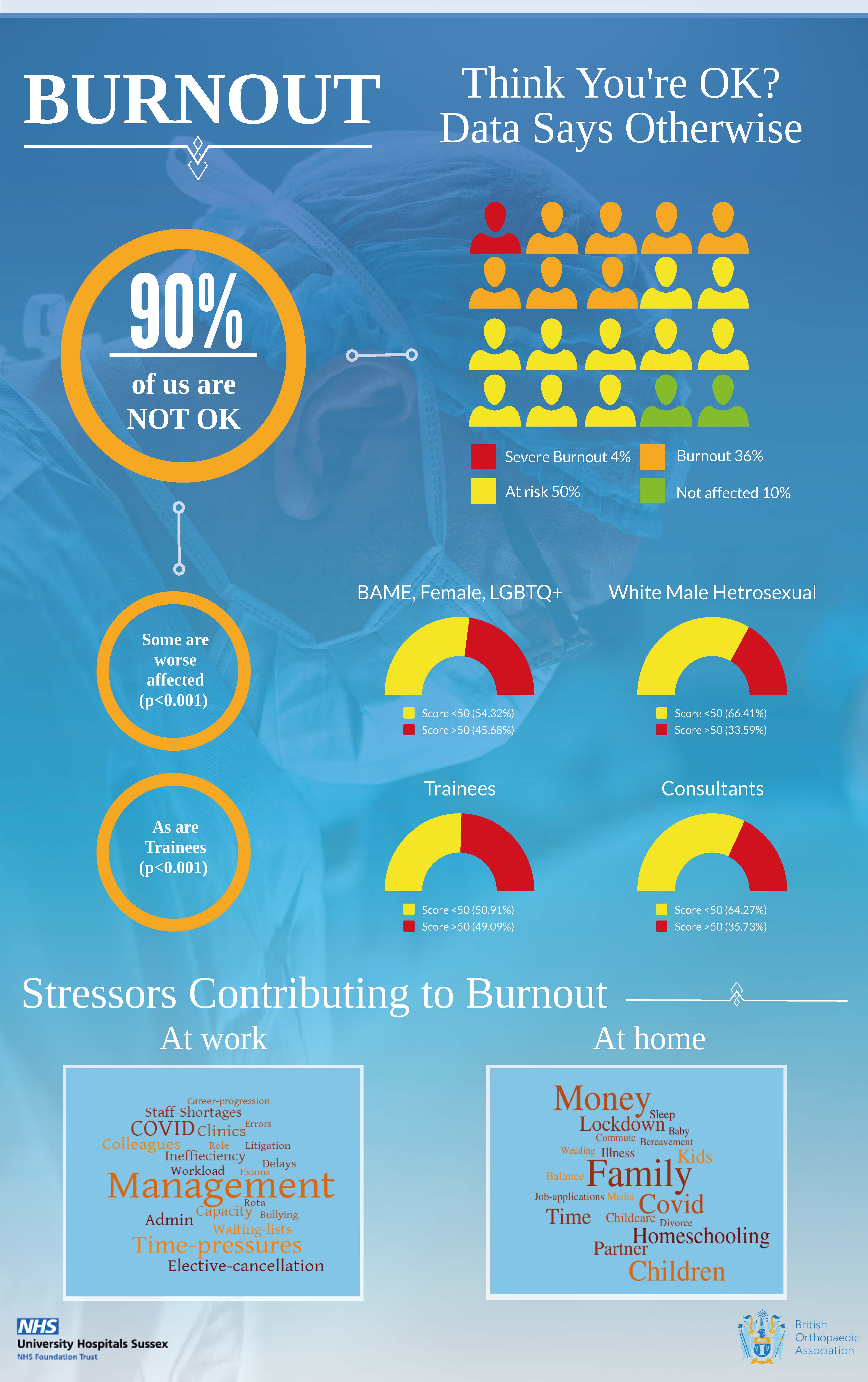

The data has then been presented in the accompanying infographic to this paper and is discussed in our key findings.

The key findings

- 40% of respondents reported a Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) score of over 50, which indicates burnout.

- A further 50% of respondents were just below this threshold and have been classified as at risk of burnout due to the cyclical and dynamic nature of this condition. They had CBI scores of between 25-50, which is in keeping with other published literature29-31.

- Those with protected characteristics, i.e. gender, race or sexuality, were found to be statistically more at risk than white, male heterosexuals. These two groupings were 49% and 51% of respondents respectively. The CBI scores over 50 were 45.6% for the BAME, Female, LGBTQ+ group versus 33.6% for the white, male heterosexual group. The t-test on this result was highly statistically significant (p<0.001).

- Trainees were more at risk of burnout than consultants. 49.1% of trainees who responded had CBI scores over 50, whereas only 35.7% of consultants who responded had CBI scores over 50. The t-test and chi squared tests were both highly statistically significant (p<0.001).

- Staff and Associate Specialists (SAS) in T&O had a similar burnout rate to the trainees and, whilst smaller in number, this was of a similar magnitude with 52.1% of SAS T&O surgeons having a CBI score over 50, compared to consultants at 35.7%. This was again highly statistically significant (p<0.001) on both t-test and chi squared tests. What was not possible to unpick from the data was how much of this effect was as part of the high levels of BAME ethnicity within the SAS T&O surgeons, or the grade at which they were working. Further work is therefore required to address the concerns of this severely affected portion of the BOA membership. For simplicity and clarity, we have not included a further image within the infographic but have highlighted our concerns to the BOA Wellbeing Initiative.

- The analysis of the qualitative data is presented in a pair of word clouds generated by WordItOut.

- The key work stressors were management, time pressures, COVID-19 and a number of differing ways of expressing the problems around waiting lists and elective operating. There were also enough mentions of problems with colleagues and bullying for these to appear in the list.

- The key stressors at home revolved around family stresses, particularly children, childcare and home-schooling, however money and the stress of lockdown was also mentioned regularly. (The word ‘partner’ is utilised in the word cloud as it came up in equal numbers to the word ‘wife,’ therefore these numbers were combined. It was felt that the word ‘partner’ was more appropriate.)

Discussion

These survey findings were scrutinised by the research group and discussed at the BOA Wellbeing Initiative. It was felt that the survey findings reflected cultural problems within T&O in the UK. There is clearly a gender imbalance with only 15% of survey respondents being female. This is despite over 50% of medical school entrants being female. Not only are women underrepresented but they are more at risk of burnout, with 53% having a CBI score over 50 compared to only 36% of men.

A similar finding was true for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) T&O surgeons, in that they too reported a higher rate of burnout compared to their white colleagues, 44% had a CBI score over 50 compared to 35% in the white cohort. The BAME cohort accounted for 33.3% of the survey respondents.

Whilst only a small percentage of the respondents identified as LGBTQ+, they also demonstrated a higher score than heterosexual T&O surgeons. Those who declared a sexuality had the following CBI scores above 50; heterosexual 39%, homosexual 55% and bisexual 50%.

When we created a group of those with protected characteristics of race, gender and sexuality and compared them with white, heterosexual males, the numbers were nearly equal. The BAME, Female, LGBTQ+ cohort were 49% (637) of respondents and the white, heterosexual males were 51% (661). When these two groups were compared, those with protected characteristics had a 45.6% burnout rate compared to the white, heterosexual male group who had a 33.6% burnout rate. This was compared with a t-test and had a p value <0.001, and so deemed to be highly statistically significant.

The qualitative data gives more insight into what may be driving these levels of burnout. When viewed with the concept of the six areas of work life described in Maslach’s paper22, the words that were mentioned most frequently as stressors make sense. Maslach’s model described six areas that encompass the central relationships with burnout: workload, control, reward, community, fairness and values. Where there are chronic mismatches between people and their work setting in terms of some or all of these six areas, burnout arises.

Management, time-pressures, COVID-19, and problems with waiting lists and elective practice point squarely toward a lack of control, workload pressure and a mismatch in values where difficult choices are being made. These decisions are often made by people within organisations who are not the clinicians, i.e., ‘management’.

Problems with colleagues and bullying confirm what is being seen within the quantitative data, and reflects a mismatch in the areas of fairness, community and values. Reward and fairness are also an issue when career progression is not forthcoming and is something that was cited as an issue particularly within the SAS grade. Our data corroborates research from the USA32,33 which has highlighted issues of microaggression and a decrease in psychological safety amongst surgeons, in particular women and underrepresented minorities34,35.

The stressors outside of work cannot be viewed through Maslach’s model, but the predominant issues at this difficult time revolved around family, children, homeschooling and money. Problems within long-term relationships adding additional stress to an already testing time. What was clear from some of the additional comments, which for reasons of confidentiality will not be shared in detail, was that many of the respondents were dealing with significant illness within their families, both physical and mental, which they were not able to share with colleagues. There were tragic situations where family members had died and normal grieving had not been possible due to the pandemic. Couples were separated by distance for work, and then prohibited from meeting due to the pandemic restrictions. Many respondents reported significant financial difficulties either due to their own income decreasing or because partners were furloughed or

having to undertake childcare at home. As a profession, we still seem to operate in an antiquated, patriarchal manner towards our home life, which may explain to some degree, the low number of women opting for a career in Trauma and Orthopaedics.

The stressors for trainees were often a combination of a lack of training opportunities, uncertainty around exams, young families, separation from partners and the redeployment to other departments. Many did not feel able to speak up about these issues.

The BOA has expressed its aims as, to care for patients, support surgeons and transform lives by focusing on professional practice, training and education, and research. The vision of the BOA is a vibrant, sustainable, representative orthopaedic community delivering high quality, effective care to fully informed patients36. Given the data from this survey run in conjunction with the BOA, the BOA Wellbeing Initiative is being launched to support surgeons to provide the high-quality care for our patients by ensuring a shift in focus and culture so that all Trauma and Orthopaedic surgeons and the teams they work with feel included, supported and psychologically safe. This initiative will start with a webpage on the BOA site to help those interested look at ways to care for themselves, support their teams and foster change within their organisations.

References

- Schaufeli WB, Greenglass ER. Introduction to special issue on burnout and health. Psychol Health. 2001;16(5):501-10.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-13.

- Klein J, Grosse Frie K, Blum K, von dem Knesebeck O. Burnout and perceived quality of care among German clinicians in surgery. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(6):525-30.

- Linzer M, Visser MR, Oort FJ, Smets EM, McMurray JE, de Haes HC, et al. Predicting and preventing physician burnout: results from the United States and the Netherlands. Am J Med. 2001;111(2):170-5.

- Caesar B. Double pandemic, Dr Forte and the fork in our road. Journal of Trauma and Orthopaedics. 2020;8(4):31-3.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000.

- West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1294-300.

- Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors' perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(7):1017-22.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463-71.

- Sharma A, Sharp DM, Walker LG, Monson JR. Stress and burnout in colorectal and vascular surgical consultants working in the UK National Health Service. Psychooncology. 2008;17(6):570-6.

- Siu C, Yuen SK, Cheung A. Burnout among public doctors in Hong Kong: cross-sectional survey. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18(3):186-92.

- Shanafelt TD, Raymond M, Kosty M, Satele D, Horn L, Pippen J, et al. Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(11):1127-35.

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254.

- Shanafelt T, Sloan J, Satele D, Balch C. Why do surgeons consider leaving practice? J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(3):421-2.

- Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout-depression overlap: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;36:28-41.

- Asai M, Morita T, Akechi T, Sugawara Y, Fujimori M, Akizuki N, et al. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among physicians engaged in end-of-life care for cancer patients: a cross-sectional nationwide survey in Japan. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):421-8.

- Oreskovich MR, Kaups KL, Balch CM, Hanks JB, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):168-74.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, Bechamps G, Russell T, Satele D, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62.

- van der Heijden F, Dillingh G, Bakker A, Prins J. Suicidal thoughts among medical residents with burnout. Arch Suicide Res. 2008;12(4):344-6.

- Oussedik S, MacIntyre S, Gray J, McMeekin P, Clement ND, Deehan DJ. Elective orthopaedic cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: where are we now, and where are we heading? Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(2):103-10.

- Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422.

- Bolderston H, Greville-Harris M, Thomas K, Kane A, Turner K. Resilience and surgeons: train the individual or change the system? The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2020;102(6):244-7.

- Bakker AB, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB. Burnout contagion among intensive care nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(3):276-87.

- Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Awad KM, Dyrbye LN, Fiscus LC, et al. Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-90.

- Kristensen TS, Hannerz H, Hogh A, Borg V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire--a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31(6):438-49.

- Office of National Statistics. Ethnic group, national identity and religion. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/measuringequality/ethnicgroupnationalidentityandreligion.

- Office of National Statistics. Guidance for questions on sex, gender identity and sexual orientation for the 2019 Census. Rehearsal for the 2021 Census. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/census/censustransformationprogramme/questiondevelopment/genderidentity/guidanceforquestionsonsexgenderidentityandsexualorientationforthe2019censusrehearsalforthe2021census.

- Caesar B, Barakat A, Bernard C, Butler D. Evaluation of physician burnout at a major trauma centre using the Copenhagen burnout inventory: cross-sectional observational study. Ir J Med Sci. 2020;189(4):1451-6.

- Ng APP, Chin WY, Wan EYF, Chen J, Lau CS. Prevalence and severity of burnout in Hong Kong doctors up to 20 years post-graduation: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e040178.

- Messias E, Gathright MM, Freeman ES, Flynn V, Atkinson T, Thrush CR, et al. Differences in burnout prevalence between clinical professionals and biomedical scientists in an academic medical centre: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023506.

- Balch Samora J, Van Heest A, Weber K, Ross W, Huff T, Carter C. Harassment, Discrimination, and Bullying in Orthopaedics: A Work Environment and Culture Survey. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(24):e1097-e104.

- Lin JS, Lattanza LL, Weber KL, Balch Samora J. Improving Sexual, Racial, and Ethnic Diversity in Orthopedics: An Imperative. Orthopedics. 2020;43(3):e134-e40.

- Sprow HN, Hansen NF, Loeb HE, Wight CL, Patterson RH, Vervoort D, et al. Gender-Based Microaggressions in Surgery: A Scoping Review of the Global Literature. World J Surg. 2021;45(5):1409-22.

- Torres MB, Salles A, Cochran A. Recognizing and Reacting to Microaggressions in Medicine and Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(9):868-72.

- British Orthopaedic Association. About Us. Available from: www.boa.ac.uk/about-us.html.