COVID-19 causes a SHiFT in the sands for proximal femoral fracture management?

By Michael Cronin, Mark Mullins, Praveen Pathmanaban, Paul Williams and Matthew Dodd

Swansea Bay University Health Board

Corresponding author: [email protected]

Published 14 April 2020

Introduction

“It is not surprising that in talking about uncertainty we should lean heavily on facts, just as the court of law does when interrogating witnesses. Facts form a sort of bedrock on which we can build the shifting sands of uncertainty.”

Noted statistician Dennis Lindley is quoted in his text “Understanding uncertainty” which discusses how virtually every aspect of our lives involves situations in which the outcomes are uncertain and how best to deal with them.

The advent of COVID-19 has led to major uncertainty in all aspects of our lives. The current shifting sands in our specialty reflect this with a plethora of guidance documents and advice being produced by our peer bodies. In the face of COVID-19 the GMC and BOA1 have written to support the need for pragmatism and alterations in our practice for clinical decision making on an individual patient basis.

Patients with a proximal femoral fracture are arguably the “bedrock” of our Trauma practice. But when it comes to interrogating the “facts”, for any individual case, how will we actually make these decisions in practice and how will the “court of law interrogate us as witnesses” in the future when the COVID-19 tsunami has dispersed?

Interrogation in social science terms means to ask questions about something as a way of analysing it or finding out more about it to enable the decision making process. In particular for this patient group, it can be used to help us decide how best we should treat them.

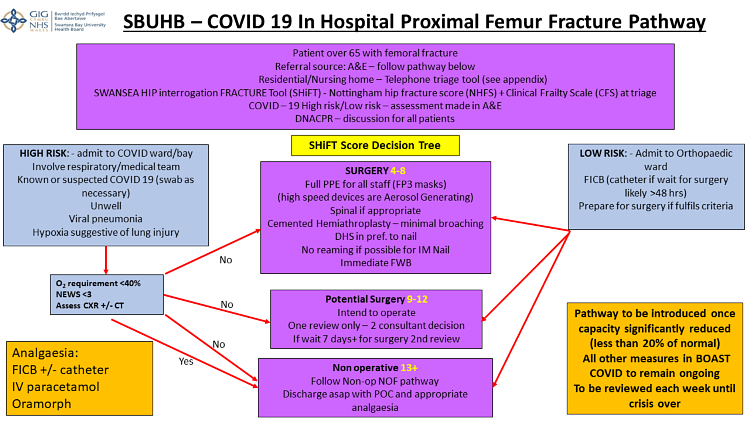

The Swansea Hip interrogation Fracture Tool (SHiFT) has been devised to enable clinical decision making in this extremely ethically and morally difficult area.

Background

Swansea Bay University Health Board (SBUHB) experiences a large annual volume of patients with a proximal femoral fracture (fractured neck of femur or #NOF). On an annual basis we treat between 500-600 proximal femoral fracture cases running a 12 hour trauma list 7 days a week, alongside 1-2 emergency ‘CEPOD’ theatres.

Our hospital covers a population of 390,000 patients and routinely operates 20 operating lists a day. Since the Governments call to prepare for the anticipated surge of COVID-19 cases, the hospital has diverted much time and resource into retraining staff and reconfiguring clinical areas. For the last two weeks, capacity in SBUHB has been severely reduced down to two emergency ‘CEPOD’ theatres to accommodate life and limb threatening surgery only. One theatre runs 24 hours a day, the other only 12 hours.

The Health Board have taken the decision to treat all operative cases as potentially COVID-19 positive. All theatre personnel are wearing PPE for aerosol generating procedures (AGP)2, including all proximal femoral fracture cases with FFP3 or N95 masks being worn by all staff. Each case is now taking two to three times longer to perform because of the PPE procedures and COVID-19 protocols required.

PPE stocks across theatres, ITU and the hospital in general are limited. However, we are being correctly advised by the Royal College of Surgeons that protecting ourselves and our staff is a priority. This has not yet led to any significant delay in treatment but placing all of these facts together means the realistic throughput of proximal femoral fracture cases has been significantly reduced.

It is against this background that all surgical specialities within SBUHB are being asked to try and determine whether all patients still appropriate for theatre or whether some could be managed conservatively.

The magnitude of unintended consequences on patient outcomes, morbidity and mortality, in non-COVID-19 medical and surgical conditions is difficult to quantify but will likely be detrimentally affected by the current approach.

In 2005/06 the UK treated 68,000 proximal femoral fracture patients, with mortality being 10% at 30 days, 20% at 4 months and 30% at 1 year after admission3. The overall figures have continued to grow but since the National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) and the introduction of best practice tariff, the national mortality figures have reduced.

In a time of limited resources we have attempted to rationalise the care we provide for this large group of patients by developing a pathway and clinical decision making tool for treatment.

Underpinning this process are the following principals:

- To continue to provide surgery for as many patients with a proximal femoral fracture as capacity will allow.

- The decision whether a patient requires surgery will be made on objective clinical grounds.

- The benefits and risks of hospital admission and surgery will be balanced with the additional risks to the individual patient due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The potential risks to others such as staff and fellow residents on return to residential and nursing home accommodation must also be taken into consideration.

- Decision making needs to be made collaboratively between Trauma and Orthopaedic surgeons and Orthogeriatricians.

- Accepting that the implementation of the pathway is likely to lead to an increase in conservative care of patients.

Methods

The aim was to make an objective scoring system that was reproducible, robust and could be used to help make informed decisions based on predicted patient outcomes.

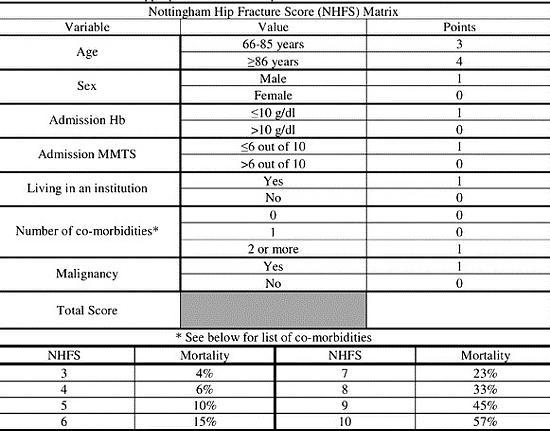

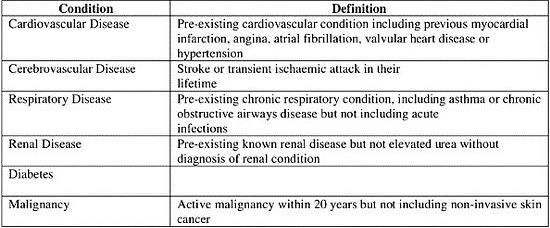

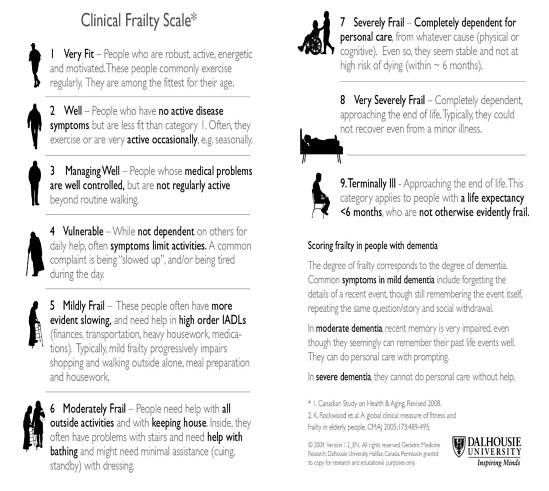

The Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS)4 is a ‘disease specific’ score that can be used to compare groups and predicted mortality. The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a ‘generic’ score which has been used extensively in COVID-19 patients as a way of helping stratify patients into groups with different ceilings of care.

The combination of a disease specific and generic score appear to be a good way of interrogating information about predicted mortality and patients pre-morbid function/ Quality of Life. The Swansea Hip interrogation Fracture Tool (SHiFT) is a simple addition of the NHFS + CFS and is designed to be used to aid in clinical decision making and triage. The minimum score possible is 4 and the maximum is 19.

We have reviewed our patient cohort from Q1 2019 to assess the suitability of the tool for patient triage and decision making.

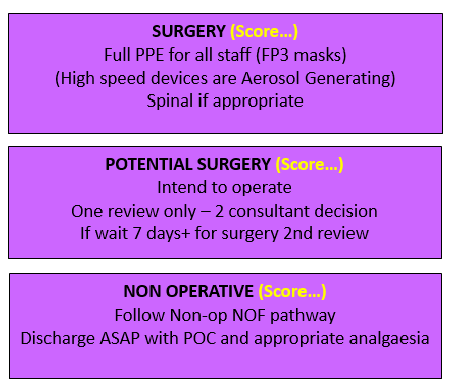

Our suggested decision making algorithm would divide inpatients into 3 groups:

Between January 1st and March 31st 2019 we admitted 124 proximal femoral fracture patients. Their SHiFT scores ranged from 6 to 15 with a whole group mortality of 26%

We further subdivided the scores into three groups in an attempt to make three separate treatment pathways:

|

Score |

Number |

Percentage of Patients |

Mortality (4 month) |

|

4-8 |

42 |

34% |

2% |

|

9-12 |

70 |

56% |

34% |

|

13+ |

12 |

10% |

58% |

The rationale would be for any individual hospital to look at their scores and case mix to decide on the size of the three groups. For example, if we wished to increase the frailest group, we could change the threshold to 12+. This would change the figures to:

|

Score |

Number |

Percentage of Patients |

Mortality (4 month) |

|

4-8 |

42 |

34% |

2% |

|

9-11 |

48 |

39% |

27% |

|

12+ |

34 |

27% |

53% |

During times of significantly low capacity (the current COVID-19 pandemic is one example), the score will be used as an objective measure to ensure the patient population is treated in order to maximise survival and quality of life. We have chosen to only introduce these tools once we have an ‘anticipated prolonged’ reduction in capacity to below 20%. These threshold decisions need to be made at an individual hospital level based on a local understanding of capacity and demand.

Patients are to be listed in order of score (Lowest first or 'fittest first') on any given day. The number to be listed depends on predicted maximum capacity (plus an extra case on standby).

Patients with higher scores may never get to the top of the list depending on number of cases presenting and capacity available.

At 7 days a further review will be undertaken to assess ongoing suitability for surgery based on:

- Ongoing clinical need (Still in pain and immobile)

- Clinical status (Still anaesthetically fit)

- Present theatre capacity

It is envisaged that at 7 days remaining patients will be converted to the non-operative group.

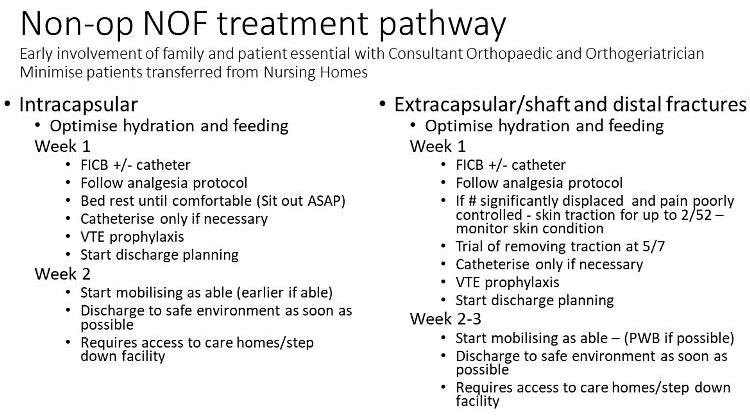

Patients in the non-operative group will follow a defined protocol:

Assessing whether the patient is COVID-19 positive will significantly affect the decision to operate or to treat non operatively depending on the clinical status and the anticipated length of wait for surgery. Patients medically compromised by COVID-19 will be treated non-operatively. The complete pathway including the thresholds we have chosen is shown below:

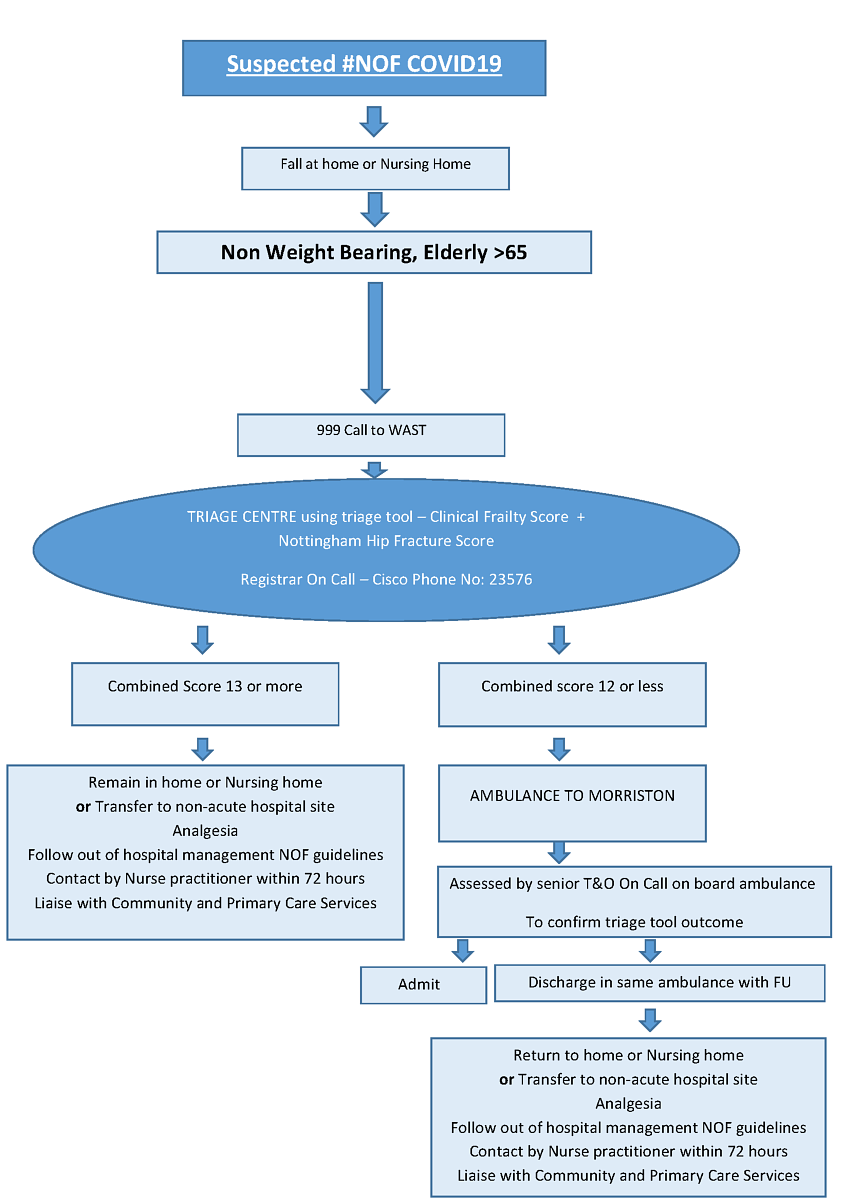

For patients in institutional care the intention is to screen the patients to reduce unnecessary admission to hospital. The attending health care staff will be told to telephone a triage number where a discussion can take place to establish the SHiFT score.

For the NHFS, the Haemoglobin will be assumed to be greater than 10 g/dl equating to a score of zero (although clearly this could change to a score of 1 at a later stage if admitted).

If the score is greater than or equal to 13 the recommendation would be to advise non operative management for the patient and therefore try to avoid admission to hospital. We accept that within this group we will only be able to treat a small proportion of patients in their own home/NH. We therefore propose to otherwise transfer these patients to a ward area on a non-acute hospital site for conservative management.

For scores of 12 or less the patient should be transferred to hospital where the patient can be assessed by the Orthopaedic Trauma team in the ambulance. There would be an opportunity to discharge the patient back to their usual point of care or transfer to our non-acute ward if the SHiFT score is found to be 13. If the patient is deemed fit they will be admitted to hospital with an intention to operate.

The pre-hospital pathway is shown below:

Work has been performed in primary care with GPs and Clusters as part of the COVID-19 preparations to get Advanced Care Plans in place for residents of residential and nursing homes to enable clinical decision making.

For patients who are not admitted to hospital a Nurse Practitioner contact review is arranged 48-72 hours later. All patients will require adequate analgesia. A full out of hospital treatment protocol is being worked on as a separate document.

Accurate documentation regarding the scoring process and decision making must be undertaken with the clinicians involved named and their GMC numbers annotated.

A decision should be made and documented on admission as to whether the patient is for DNA CPR or otherwise. This conversation may be made easier using the excellent advice recently published on dealing with this topic specifically to COVID-19 patients5.

Family members should be informed of the management plan, even if this must be done remotely by telephone.

Clinical judgment must guide treatment at a local level. There is Executive level understanding that these decisions are being made in the interest of the more global picture within the Health Board.

Weekly review of the figures will be performed to ensure the group sizes are correct to match capacity. However, we do not envisage changing the threshold levels to match capacity on a day to day basis as this would cause inconsistency in the approach with patients and add a level of confusion in the system.

Discussion

Data from the UK National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD)6 in 2013 indicated that 2.6% of patients with fractures of the femoral neck are treated by conservative means. Although it is often thought that patients undergoing non-surgical management have worse outcomes both Moulton et al.7 and Gregory et al.8 have provided evidence to support the non-operative management of some patients with intracapsular fracture.

Handoll et al.9 Performed a Cochrane review most recently updated in 2008. This included 4 studies on extra-capsular fractures and concluded no difference in medical complications, mortality and long term pain between operative and non-operative groups. However, they did find that surgery resulted in higher rate of healing, better leg length, shorter length of stay and higher chance of return to their original residence.

We use the above evidence and national guidelines to justify surgery on a daily basis. However, we must be acutely aware that all of these conclusions are based on healthcare systems where capacity is not outstripped by demand.

It may appear we are pushing against the tide of conventional wisdom for our patients but, these changes are not without good reason. As doctors we are all taught to do what is in the best interest of the patient in front of you. However, an ethical dilemma comes when we are being forced to sacrifice normal service capacity to ‘plan’ for the COVID-19 pandemic, the size and effect of its peak, still unknown.

Once the decision was made centrally to essentially act in the best interest of the entire population, we as clinicians are no longer able to do what is in the best interest of a single patient in front of us. We have to do what is in the best interest of the whole population we serve. With the limited capacity we now have available for treating our proximal femoral fracture patients we have to decide whether we treat everyone in a new way, giving up our normal model of ‘Sickest First’ to a new model of ‘Fittest first’.

If we cannot treat all should we treat those most likely to survive and those likely to regain most quality of life? This ethical dilemma was discussed in the World Health Organisation global consultation on pandemic planning in 200610. Within it clearly states that ‘The principle of utility, that is, acting so as to produce the greatest good is valid even if it means bringing greater good to a small number of people than a smaller good to a larger group’.

The NHFS and the CFS both confirm that patients with higher scores have higher mortality and poorer pre-morbid quality of life. Combining the two scores to give the SHiFT score at this time of the COVID-19 pandemic and its wider implications, appears to provide a logical method to support a shift towards preventing hospital admission and non-operative management in certain individuals with a fracture neck of femur.

The situation we find ourselves in at SBUHB will not be unique. Interestingly, our decision 2 weeks ago, to treat all patient as COVID +ve in theatre was well before many other parts of the country, who have now adopted this policy. The rapidly changing understanding of the pandemic itself is mirrored by a rapidly changing understanding of the implications it has on our remaining practice.

Conclusions

In these times of COVID-19 uncertainty, interrogation of the evidence surrounding the management of patients with a proximal femoral fracture and application to individual hospitals clinical circumstances indicates that non-operative management may be more justifiable than we once thought. Only when the sands have stopped shifting will we perhaps understand fully to what extent.

References

- British Orthopaedic Association (2020). Emergency BOAST: Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-boasts-combined.html.

- Public Health England (2020). Reducing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 in the hospital setting. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/reducing-the-risk-of-transmission-of-covid-19-in-the-hospital-setting.

- Dr Foster Intelligence (2012). Hospital guide 2012. Available at: http://download.drfosterintelligence.co.uk/Hospital_Guide_2012.pdf.

- Wiles MD, Moran CG, Sahota O, Moppett IK. Nottingham Hip Fracture Score as a predictor of one year mortality in patients undergoing surgical repair of fractured neck of femur. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(4):501-4.

- Johansen A. Talking about ceilings of treatment when clerking older trauma patients. The Transient Journal of Trauma, Orthopaedics and the Coronavirus. April 2020. Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/policy-engagement/journal-of-trauma-orthopaedics/journal-of-trauma-orthopaedics-and-coronavirus/talking-about-ceilings-of-treatment-when-clerking.html.

- Hip Fracture Database. National Hip Fracture Database National Report 2013. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2013.

- Moulton LS, Green NL, Sudahar T, Makwana NK, Whittaker JP. Outcome after conservatively managed intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97(4):279–82.

- Gregory JJ, Kostakopoulou K, Cool WP, Ford DJ. One-year outcome for elderly patients with displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck managed non-operatively. Injury. 2010;41(12):1273-6.

- Handoll HH, Parker MJ. Conservative versus operative treatment for hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD000337.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2007. Ethical and Legal Considerations in Mitigating Pandemic Disease, Workshop Summary. Chapter 4: Ethical Issues in Pandemic Planning and Response. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.;2007.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Nottingham Hip Fracture Score

Appendix 2: Clinical Frailty Scale

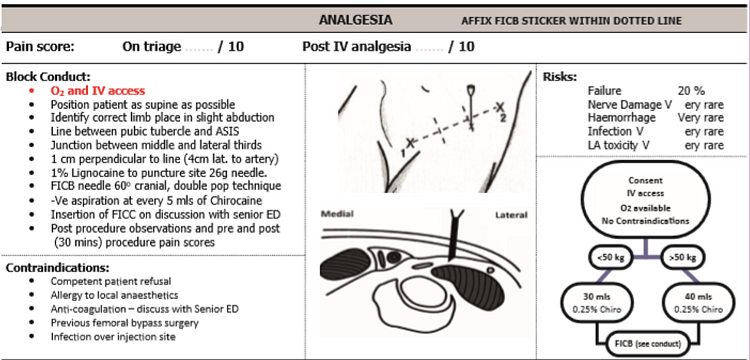

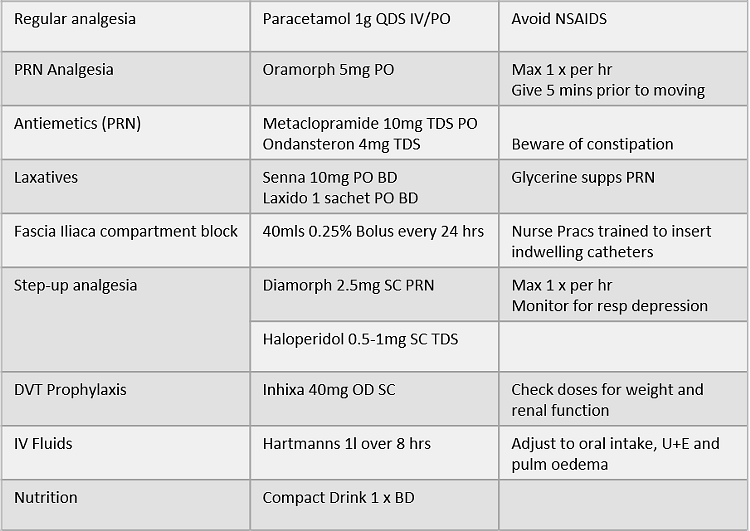

Appendix 3: Analgesia ladder + Femoral nerve block criteria